Politicians specialize in bad policy, but they go overboard during election years.

It’s especially galling to hear Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton compete to see who can make the most inane comments about the financial sector.

This is why I felt compelled last month to explain why the recent financial crisis had nothing to do with the absence of “Glass-Steagall” regulations.

Today, I want to address Dodd-Frank, the legislation that was imposed immediately after the crisis by President Obama and the Democrat-controlled Congress.

I’m tempted to focus on the fact that the big boys on Wall Street, such as Goldman-Sachs, supported the law. It’s galling, after all, to hear politicians claim Dodd-Frank was anti-Wall Street legislation.

But there are more important points to consider, including the fact that the law doesn’t prevent or preclude bailouts.

Writing for today’s Wall Street Journal, Emily Kapur and John Taylor identify key problems with the Dodd-Frank bailout legislation.

Sen. Sanders and others on both sides of the aisle have a point. The 2010 Dodd-Frank financial law, which was supposed to end too big to fail, has not. Dodd-Frank gave the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. authority to take over and oversee the reorganization of so-called systemically important financial institutions whose failure could pose a risk to the economy. But no one can be sure the FDIC will follow its resolution strategy… Neel Kashkari, now president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, says government officials are once again likely to bail out big banks and their creditors.

Most important, they propose a new Chapter 14 of the bankruptcy code so that insolvent institutions – regardless of their size – are liquidated.

The solution is not to break up the banks or turn them into public utilities. Instead, we should do what Dodd-Frank failed to do: Make big-bank failures feasible without tanking the economy by writing a process to do so into the bankruptcy code… Chapter 14 would impose losses on shareholders and creditors while preventing the collapse of one firm from spreading to others. …the court would convert the bank’s eligible long-term debt into equity, reorganizing the bankrupt bank’s balance sheet without restructuring its operations. …Other reforms, such as higher capital requirements, may yet be needed to reduce risk and lessen the chance of financial failure. But that is no reason to wait on bankruptcy reform. A bill along the lines of the chapter 14 that we advocate passed the House Judiciary Committee on Feb. 11. Two versions await action in the Senate. Let’s end too big to fail, once and for all.

Amen. When big institutions go under, shareholders and bondholders should be the ones to bear the costs, not taxpayers.

Unfortunately, unless a new Chapter 14 of the bankruptcy code is created, it’s quite likely that regulators and politicians will simply opt for more TARP-style bailouts if big firms get in trouble.

So Dodd-Frank didn’t really do the one thing that was necessary.

But it did do a lot of things that make the system more costly and clunky.

Hester Pierce of the Mercatus Center explains that Dodd-Frank expanded regulation based on the theory that regulators can understand and plan the financial sector.

Dodd-Frank—built on the premise that markets fail, but regulators do not—places great faith in regulators to identify and stop problems before they develop into a crisis. …Dodd-Frank, despite language to the contrary, keeps the door open for future bailouts. …Dodd-Frank includes many provisions that are not related to financial stability, but fails to deal with key problems made evident by the crisis. …Dodd-Frank’s drafters chose to leave many key decisions to regulators. The contours of systemic risk, for example, were left to regulators to define. Moreover, because the prevailing narrative of the crisis focused on market failure, Dodd-Frank expanded regulators’ authority to shape the financial system. In addition to their substantial rule-writing responsibilities, under Dodd-Frank regulators now play a central role in monitoring, planning, and managing the financial markets.

Most worrisome, Hester notes that Dodd-Frank has provisions that benefit the big firms and may make them more likely to get bailouts.

Dodd-Frank gives FSOC broad powers to designate nonbank financial institutions and financial market utilities (such as derivatives clearinghouses) systemically important. …Designated firms are likely to be perceived as the firms the government is likely to rescue… Dodd-Frank was supposed to mark the end of taxpayer bailouts of financial firms. This pledge is undermined in several ways by the statute’s other provisions and the regulatory-centric approach that cuts across the whole statute. …The pressure on regulators to conduct bailouts is likely to be particularly strong with respect to systemically important institutions. …Regulatory failure played an important role in the last crisis by concentrating resources in the housing sector, encouraging reliance on credit-rating agencies, and driving financial institutions to concentrate their holdings in mortgage-backed securities. Dodd-Frank gives regulators more authority and broad discretion to shape the financial sector and the firms operating within it. When the regulators fail at this ambitious mission, they will again face internal and external pressure to cover those failures with a taxpayer-funded bailout.

Two other Mercatus experts, Patrick McLaughlin and Oliver Sherouse, show that regulators were among the biggest beneficiaries of the law. The law has led to a massive explosion in red tape.

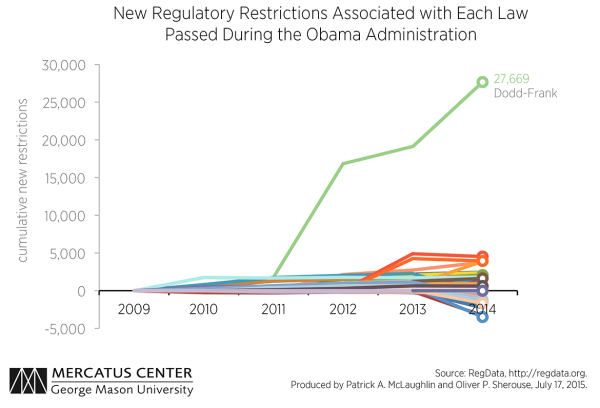

The statute, which itself was 848 pages long, directed dozens of regulatory agencies to revise or create new regulations addressing the financial system in the United States. Those agencies responded with hundreds of new rules that will govern financial markets, on a scale that vastly exceeds any previous regulation of financial markets, and dwarfs the regulations that accompanied all other legislation enacted during the Obama administration. …Dodd-Frank…is associated with more than five times as many new restrictions as any other law passed since January 2009, for a total of nearly 28,000 new restrictions. In fact, it is associated with more new restrictions than all other laws passed during the Obama administration put together.

Here’s a rather sobering chart from the report.

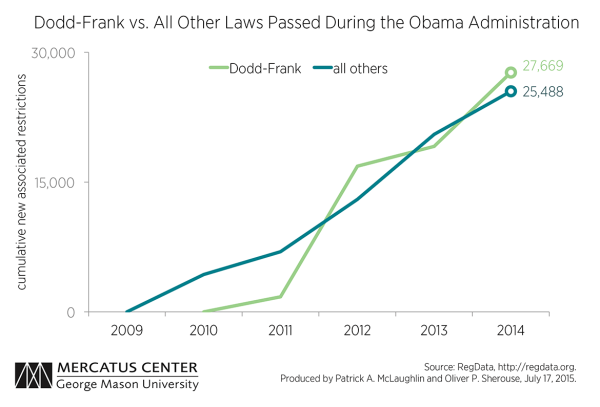

Amazingly, the red tape generated by Dodd-Frank is roughly equal to all the regulation generated by every other law that’s been imposed during the Obama years.

Including the notoriously Byzantine Obamacare legislation.

All these new rules actually create a competitive advantage for big financial institutions.

Peter Wallison of the American Enterprise Institute has a must-read study on how Dodd-Frank imposes disproportionately heavy costs on small banks and small businesses.

…the reason for the slow recovery is the Dodd-Frank Act, enacted in 2010, which placed heavy regulatory costs and new restrictive lending standards on small banks. This in turn reduced the ability of these banks to finance small businesses, particularly the start-up businesses which are the engine of employment and economic growth. Large businesses have not been subject to the same restrictions because they have access to the capital markets, and their growth has been in line with prior recoveries. …recoveries after financial crises tend to be sharper than other recoveries, not slower as some have suggested. It is likely that, without the repeal or substantial reform of Dodd-Frank, the U.S. economy will continue to grow only slowly into the future. ……whatever regulatory costs are imposed on banking organizations— whether they be $2 trillion banks like JPMorgan Chase, $50 billion banks or $50 million banks— the larger the bank the more easily it will be able to adjust to these costs.

What’s especially frustrating is that the law was imposed because of a fundamental misunderstanding of what caused the crisis.

…the incoming administration of Barack Obama and the Democratic supermajority in Congress blamed the crisis on insufficient regulation of the private financial sector. This narrative, although factually unsupported, gave rise to the Dodd-Frank Act, which imposed significant new regulation on the US financial system but did virtually nothing to reform the government policies that gave rise to the financial crisis. …In developing and adopting the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress and the administration did not appear to be concerned about placing additional regulatory costs on the financial system.

Here’s the bottom line. Regulation is no replacement for market discipline.

And bankruptcy needs to be part of that discipline. After all, capitalism without bankruptcy is like religion without hell.

P.S. To give you an idea of how unserious politicians are, the Dodd-Frank law didn’t end bailouts, but it did create new racial and sexual quotas. So I guess we can take comfort in the fact that the bureaucracy will reflect all of America the next time they rip off taxpayers.