As a general rule, I’m not overly concerned about debt, even when looking at government red ink.

I don’t like deficit and debt, to be sure, but government borrowing should be seen as the symptom. The real problem is excessive government spending.

This is one of the reasons I’m not a fan of a balanced budget amendment, Based on the experiences of American states and European countries, I fear politicians in Washington would use any deficit-limiting requirement as an excuse to raise taxes.

I much prefer spending caps, such as those found in Hong Kong, Switzerland, and Colorado. If you cure the disease of excessive government, you automatically ameliorate the symptom of too much borrowing.

That being said, the fiscal chaos plaguing European welfare states is proof that there is a point when a spending problem can also become a debt problem. Simply stated, the people and institutions that buy government bonds at some point will decide that they no longer trust a government’s ability to repay because the public sector is too big and the economy is too weak.

And even though the European fiscal crisis no longer is dominating the headlines, I fear this is just the calm before the storm.

For instance, the data in a report from Citi about the looming Social Security-style crisis are downright scary.

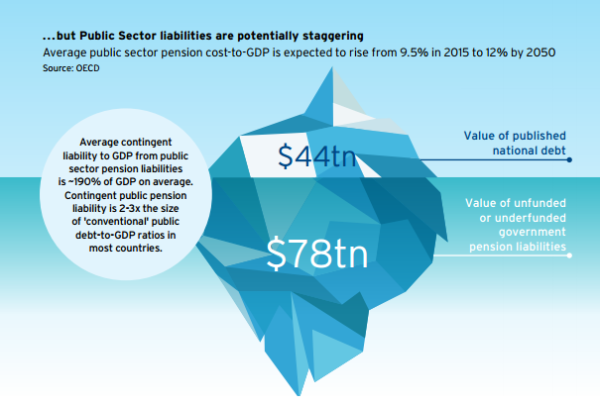

…the total value of unfunded or underfunded government pension liabilities for twenty OECD countries is a staggering $78 trillion, or almost double the $44 trillion published national debt number.

And the accompanying chart is rather appropriate since it portrays this giant pile of future spending promises as an iceberg.

And when you look at projections for ever-rising spending (and therefore big increases in red ink) in America, it’s easy to see why I’m such a strong advocate of genuine entitlement reform.

But it’s also important to realize that government policies also can encourage excessive debt in the private sector.

Before digging into the issue, let’s first make clear that debt is not necessarily bad. Households often borrow to buy big-ticket items like homes, cars, and education. And businesses borrow all the time to finance expansion and job creation.

But if there’s too much borrowing, particularly when encouraged by misguided government policies, then households and businesses are very vulnerable if there’s some sort of economic disruption and they no longer have enough income to finance debt payments. This is when debt becomes excessive.

Yet this is what the crowd in Washington is encouraging.

Writing for the Wall Street Journal, George Melloan warns that misguided “stimulus” and “QE” policies have created a debt bubble.

…while Mr. Bernanke and Ms. Yellen were trying to prevent deflation, the federal government was engineering its cause, excessive debt. And the Fed abetted the process by purchasing trillions of dollars of government paper, aka quantitative easing. Near-zero interest rates also have encouraged consumers and business to releverage. Cars are now financed with low or no-interest five-year loans. With the 2008 housing debacle forgotten, easier mortgage terms have made a comeback. Corporations also couldn’t let cheap money go to waste, so they have piled up debts to buy back their own stock. Such “investment” produces no economic growth, but it has to be paid back nonetheless. Amid the Great Recession, many worried that the entire economy of the U.S., or even the world, would be “deleveraged.” Instead, we have a new world-wide debt bubble.

The numbers he shares are sobering.

Global debt of all types grew by $57 trillion from 2007 to 2014 to a total of $199 trillion, the McKinsey Global Institute reported in February last year. That’s 286% of global GDP compared with 269% in 2007. The current ratio is above 300%.

Professor Noah Smith writes in Bloomberg about research showing that debt-fueled bubbles are especially worrisome.

…since debt bubbles damage the financial system, they endanger the economy more than equity bubbles, which transmit their losses directly to households. Financial institutions lend people money, and if people can’t pay it back — because the value of their house has gone down — it could cause bank failures. …Economists Oscar Jorda, Moritz Schularick, and Alan Taylor recently did a historical study of asset price crashes, and they found that, in fact, debt seems to matter a lot. …To make a long story short, they look at what happened to the economy of each country after each large drop in asset prices. …bubbles make recessions longer, and credit worsens the effect. …the message is clear: Bubbles and debt are a dangerous combination.

To elaborate, equity and bubbles aren’t a good combination, but there’s far less damage when an equity bubble pops because the only person who is directly hurt is the person who owns the asset (such as shares of a stock). But when a debt bubble pops, the person who owes the money is hurt, along with the person (or institution) to whom the money is owed.

Desmond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute adds his two cents to the issue.

…the world is presently drowning in debt. Indeed, as a result of the world’s major central banks for many years having encouraged markets to take on more risk by expanding their own balance sheets in an unprecedented manner, the level of overall public and private sector indebtedness in the global economy is very much higher today than it was in 2008 at the start of the Great Economic Recession. Particularly troublesome is the very high level of corporate debt in the emerging market economies and the still very high public sector debt levels in the European economic periphery. …the Federal Reserve’s past policies of aggressive quantitative easing have set up the stage for considerable global financial market turbulence. They have done so by artificially boosting asset prices and by encouraging borrowing at artificially low interest rates that do not reflect the likelihood of the borrower eventually defaulting on the loan.

In other words, artificially low interest rates are distorting economic decisions by making something (debt) seem cheaper than it really is. Sort of financial market version of the government-caused third-party payer problem in health care and higher education.

And Holman Jenkins of the Wall Street Journal makes the very important point that debt is encouraged by bailouts and subsidies.

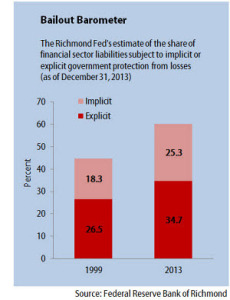

Big banks aren’t automatically bad or badly managed because they are big, but it’s hard to believe big banks would exist without an explicit and implicit government safety net underneath them. …None of this has changed since Dodd-Frank, none of it is likely to change. …we know where the crisis will come from and how it will be transmitted to the financial system. The Richmond Fed’s “bailout barometer” shows that, since the 2008 crisis, 61% of all liabilities in the U.S. financial system are now implicitly or explicitly guaranteed by government, up from 45% in 1999. …Six years after a crisis caused by excessive borrowing, McKinsey estimates that even visible global debt has increased by $57 trillion, while in the U.S., Europe, Japan and China growth to pay back these liabilities has been slowing or absent.

The bottom line is that government spending programs directly cause debt, but we should be just as worried about the private debt that is being encouraged and subsidized by other misguided government policies.

And surely we shouldn’t forget to include the pernicious role of the tax code, which further tilts the playing field in favor or debt.