The International Criminal Court: A Case of Politics Over Substance

March 2015

By Brian Garst

Executive Summary

Prior to its creation the idea for an International Criminal Court (ICC) was portrayed by separate quarters as either a bold step forward for justice or as a new international boogeyman that would follow a long line of international organizations plagued by ineffectiveness and corruption.

After twelve years, the ICC has failed to establish legitimacy in the eyes of many. It has prosecuted just 22 cases across 9 situations and secured only 2 convictions.

This paper will examine the rationale for the ICC and gauge its effectiveness through both theoretical and observational critiques, including answering whether the Court is beholden to political pressures, while seeking explanation for its apparent fixation on Africa as atrocities in other parts of the world go largely ignored.

In addition, consideration will be given to a growing body of academic research pointing to shortcomings at the ICC. All together, these issues suggest that the ICC’s flaws may be insurmountable, and a better approach is needed for dealing with global atrocities.

Introduction

Efforts at establishing an international criminal court can be traced back to the early 19th Century and the Franco-Prussian War. The call was picked up again at the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, and ad hoc tribunals – at Nuremberg and Tokyo – were later created to try the losers of World War II. But it wasn’t until after several high-profile conflicts in the early 1990s – such as in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Rwanda – that the effort was picked up in earnest and eventually culminated in the creation of the International Criminal Court.

Unlike the International Court of Justice, the judicial branch of the U.N. used to resolve disputes between nations, the International Criminal Court was intended to function largely independent of global political structures, and its creation was celebrated by human-rights groups as a new avenue for the pursuit of international justice. Human Rights Watch called it “a historic step forward for the protection of human rights and enforcement of international law.”1 Amnesty International said it represents “a major breakthrough in international justice.”2 A group of Democratic Congressmen also endorsed the Rome Statute’s goal to “create a permanent mechanism to hold perpetrators of atrocities accountable.”3

At the same time, critics warned that ICC prosecutions would be ideologically based, and that its actions could threaten the fragile peace of transitional governments.4 They also compared the Court unfavorably to the legal traditions and standards of the United States and other developed nations – through a lack of jury trials and a return to a time when defendants could be dragged to a distant land for trial away from their peers – and further found only a conditional right for defendants to confront their accusers.5 The crimes the Court was created to prosecute were also criticized as excessively vague.6

Now that the ICC has been operating for a dozen years, which side got it right? Has it promoted justice, or is it too politicized and its faults too significant to overcome? Academic researchers overwhelmingly find there’s little evidence to suggest that the Court accomplishes its goal of deterring crimes against humanity and other atrocities, which is a primary stated goal according to both the Rome Statute and its most vocal supporters. ICC intervention may even exacerbate ongoing conflicts. Poor investigative procedures and lax evidentiary standards also raise the question of whether or not the ICC is even capable of the basic judicial function of determining guilt or innocence. Finally, the Court’s credibility is severely undermined by its vulnerability to politics and obsession with Africa to the exclusion of other regions.

Brief Overview of the ICC

Although the Rome Statute, which authorizes creation of the ICC and establishes its legal boundaries, was adopted in 1998, it didn’t enter force until 2002 when the threshold of 60 state ratifications was reached. There are today 123 states and recognized jurisdictions party to the Statute.7 Thirty-one additional nations signed the Rome Statute but have not ratified it. Notable nations that have not ratified include the United States, Israel, China, Saudi Arabia, India and Pakistan.

Participation in the ICC is not uniform. Almost all of Europe, South America and the Caribbean are members. Most African nations also participate with a few holdouts. Asia and the Middle East, however, are more lightly represented.

For those that have joined, the Rome Statute claims for the ICC jurisdiction over war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity, and offenses against the administration of justice (defined as certain actions designed to thwart ICC investigations). A provision granting jurisdiction over crimes of aggression was also included, but additional criteria must be met before it comes into force.

There are three ways provided in which ICC cases can be initiated: through referral from the United Nations Security Council, through referral by a State Party to the Rome Statute, and through instigation by the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) based on information received through other sources.8 ICC jurisdiction also requires that either the state in whose territory the alleged crime was committed or the home nation of the accused be parties to the statute. The Security Council, however, can use its authority in the U.N. to bind non-State Parties to the ICC.

Nations party to the statute provide most of the funding for the Court, proportioned by ability to pay using the same methods as the United Nations. More than a third of the ICC’s contributions come from Britain, Germany, and France. The U.N. may also provide additional funds through vote by its General Assembly, and states, NGOs, and individuals can provide voluntary support to the Court or its victim’s trust fund. Judges are selected from among member nations by vote of the Court’s governing body, the Assembly of States Parties. The 18 total judges are divided evenly between three divisions – Pre-Trial, Trial, and Appeals. The ICC itself has no law enforcement agents or prison facilities, but relies on member states to provide these functions.

A Flawed Institution

The Court continues to face existential challenges even post-ratification of the Rome Statute. The most fundamental has been the need to establish and maintain legitimacy. As a supranational body granted authority by the same nation-states that it depends upon both for financing and execution of its orders, the ICC relies heavily on the good faith cooperation of its members. It has no police force to execute indictments or jails to house the convicted. It also relies on governments for assistance in carrying out investigations and gathering evidence. All of these pose serious challenges for an organization that must potentially prosecute members of those same governments.

The Questionable Assumptions of International Courts

The ICC is founded on the idea that “justice” can be delivered through international law – indeed, that there is a universally accepted notion of how justice is served among victims. Research provides considerable reason to question whether that is an accurate assumption. A comprehensive analysis of transcripts conducted by William and Mary Law Professor from three recent international tribunals – the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the Special Court for Sierra Leone, and the East Timor Special Panels for Serious Crimes – uncovered major flaws in the typical fact-finding process which raise serious questions about the viability of a dedicated international court.

Given the nature of the crimes they investigate, international courts are heavily dependent upon eyewitness accounts, which are generally treated as unreliable in domestic court systems. Despite knowledge of the weakness of eyewitness accounts, detailed review of their transcripts revealed some of the testimony relied upon by international tribunals has been extremely suspect. In one case, witnesses were asked to identify a male from a picture of a group of individuals, but in the picture he was the only man, and he even had a red mark on his shirt to help him stand out.9 In other cases, the disconnect between questions asked of witnesses and the answers provided was so vast as to clearly demonstrate that the witness had no understanding of the question, and yet was still deemed to be credible.10

Both the structure of the ICC and the calls for its creation emerged from these tribunals, and there’s little evidence that it has improved fact-finding procedures. In a comprehensive review of ICC witness procedures, the International Bar Association (IBA) found that “The Court’s reliance on witnesses, its inability to consistently access witnesses and to compel their attendance in The Hague is potentially a serious impediment to its effective functioning.”11 Of particular concern are cases involving witnesses in non-States Parties to the Rome Statute, where difficulties in reaching witnesses and bringing them to the Hague for testimony are most pronounced, and may introduce unfairness by disproportionately impacting the defense.12 But even if the Court has dramatically improved on its predecessors’ lax standards, it may still be doing more harm than good.

Much more is at stake in the realm of international politics and conflict than typical courts must deal with. The pursuit of justice is not always compatible with maintaining peace and security. Increasingly research is finding that ICC activities can have negative impact on mediation and other efforts at conflict resolution.13 If allowing an individual perpetrator – even one responsible for heinous war crimes, genocide, or crimes against humanity – to escape accountability is the cost to end or avoid conflict and significant loss of life, is it worth paying?

In South Africa post-apartheid leaders emphasized reconciliation over a narrow-minded pursuit of retribution and established the Truth and Reconciliation Committee, which is largely credited with doing just that – establishing truth and reconciliation.14 In Sudan, on the other hand, ICC indictment of President al-Bashir bolstered his popularity as his core constituency rallied around the flag in response to a perceived attack from outsiders.15 It also emboldened Darfur rebel groups to walk away from a peace deal painstakingly crafted with the assistance of the African Union and the international community.16

Similarly, an indicted leader might be spurred into hanging on with greater tenacity to the reins of power which he can use to avoid prosecution. Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi may have been so motivated when the ICC announced indictments with unprecedented speed a mere two months after the case was referred by the Security Council.17 Despite widely being described as a court of last resort, in Libya the ICC wasted no time waiting to see if Gaddafi would be held accountable by a new government. Given the unusual haste at which the Court proceeded, there’s reason to question whether it was acting under political pressure from NATO members that had also already intervened in the civil war.

It’s impossible to know whether a peaceful resolution with Gaddafi would have been likely were there not a looming threat of prosecution, but it was an unnecessary complication at a contentious moment – a fact which world leaders apparently belatedly realized, as they eventually attempted to offer quiet assurances that he would be allowed to leave unharmed if he agreed to hand over power.18

An Ineffective Deterrent

One speculated benefit of establishing a permanent international court was that it would provide a greater deterrent effect than was likely from the use of ad hoc tribunals, such as those which prosecuted war crimes in Rwanda and Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. The ICC and its supporters see deterrence as a primary purpose of the Court. It is cited in the Preamble of the Rome Statute alongside the goal of ending impunity, and the Court’s first president said, “By putting potential perpetrators on notice that they may be tried before the Court, the ICC is intended to contribute to the deterrence of these crimes.”19

It is doubtful that the ICC has or will ever produce significant deterrence effects. Bad actors have little reason to fear the Court given the extremely low likelihood of facing trial, much less conviction. The lack of clear enforcement mechanisms and the reliance on domestic cooperation also means that so long as a potential defendant holds office, or enjoys the protection of those holding office, the ICC has few if any remedies to obstruction.

Recent reports from ICC supporters claim to find deterrent effects, generally around the margins, and owes as much to the general involvement of the international community than the specific form of the ICC.20 The types of crimes that are the focus of the Court – genocide, war crimes, etc. – are unlikely to be significantly impacted. If there is a small effect, it is sure to be swamped by other factors known to correlate with the likelihood of atrocities, such as a lack of democratic institutions and social norms, regime upheaval, and poverty.21

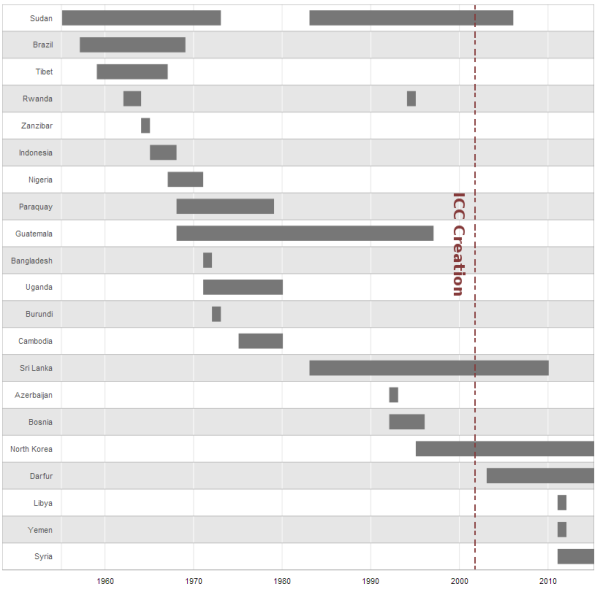

In the case of genocide, perhaps the worst of the crimes addressed by the ICC, there’s yet to be a noticeable change in the incident rate since the Court’s creation (see Figure 1). A growing body of academic studies provide yet further support that there is little if any deterrent effect created through international justice. In a study of international criminal courts and deterrence Julian Ku and Jide Nzelibe stated, “We believe [international criminal tribunal] prosecutions will be unlikely to have any meaningful deterrence effect.”22 Brookings Institution scholars Jacqueline Geis and Alex Mundt observed, “there is little empirical evidence to suggest that the possibility of international criminal indictments for mass atrocity crimes serve as a deterrent or moderating force on government and rebel leaders.”23 It’s also been argued that the ICC’s focus on pursuing only the most responsible parties – namely national leaders – is in conflict with the goal of deterrence.24

Figure 1

Acts and Lengths of Genocide Since WWII

Source: Inter-Parliamentary Alliance for Human Rights and Global Peace

Politicizing Justice

Some nations have bought into the ICC heavily in both theory and practice, but there is a growing regional divide weakening the Court. Evidence of this fracture was seen at the UN’s 2014 annual performance review of the ICC. Some nations, particularly in Europe, praised the Court and its performance. Others, like Hungary, offered support for the objectives of the Rome Statute but warned that the Court was not immune from politics. But there were also strong criticisms, particularly from Africa.

Kenya scolded the Court for having an abysmal track record and charged that it was representing only the political values of a narrow group of countries.25 Sudan, not a party to the Rome Statute, also called the Court just another tool in international conflicts and unduly focused on Africa. Both nations at the time had high-ranking officials with cases pending before the Court, so it is tempting that these charges be dismissed as efforts to muddy the water and protect certain parties from potential punishment. But another nation not under review echoed many of the same complaints. Algeria claimed politicization and misuse of indictments targeting African nations, along with disappointment on behalf of the entire continent that an African Union request to defer proceedings in accordance with Article 16 of the Rome Statute was unceremoniously rebuffed.26

These complaints are significant because African nations constitute the largest regional block of ICC members, and the cooperation of a nation whose citizens or leaders are on trial is necessary for almost any case to be resolved. The relationship between African nations and the ICC has deteriorated to the point that the African Union adopted a resolution declaring that sitting heads of state were not to appear before the Court.27 The inability of the ICC to engender cooperation also helps explain why 13 arrest warrants remain outstanding.28

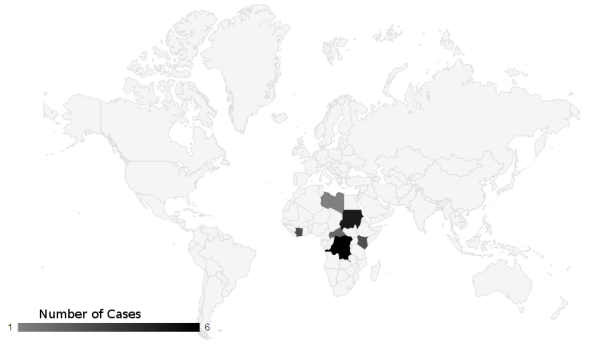

The fact that all of the 22 cases across 9 situations prosecuted to date by the ICC have originated in Africa (see Figure 2) is consistent with complaints from representatives of African nations. African criticism of the ICC is not absolute, though. When participating in meetings of ICC States Parties, a number of African nations provide statements of support, though often with important caveats and concerns.29 How much of the support is sincere and how much is empty rhetoric offered in an effort to secure concessions is difficult to gauge.

Figure 2

All Cases Brought Before the ICC*

Source: ICC; *Two situations, in Mali and the Central African Republic, are open but have no cases filed

By itself the exclusive focus on Africa doesn’t prove that prosecutions are motivated or influenced by politics. Plausible alternatives exist. One possible explanation is that all the crimes worth prosecuting have occurred in Africa. A cursory survey of recent events easily demonstrates that’s not the case, however. North Korea is an obvious source of ongoing atrocities. The ICC has also not involved itself beyond the occasional preliminary examination in any international terrorism cases. Other recent examples of cases not strongly pursued include Burma, Venezuela, and Colombia. And in 2014 almost 60 nations openly called for Syria to be referred to the ICC, but the effort was blocked by opposition from China and Russia despite 13 of 15 members of the U.N. Security Council voting in favor.30

This leads to the more likely possibility that, while Africa may or may not be a victim of political targeting, other regions are being avoided by the Court or protected by major powers. The Security Council, intended to be a primary means of bringing cases to the Court, is highly politicized. Five nations hold veto power – the United States, United Kingdom, China, France and Russia – which is routinely used to protect national and regional interests. North Korea, as an example, is unlikely to be referred through the Security Council because China asserts regional dominance and the right to solve disputes within its sphere of influence.

There are other means by which a case can be taken up at the ICC than through Security Council referral, but political pressures are just as relevant in those circumstances as well. China is not a member of the ICC, but its aura of protection over North Korea must necessarily concern a Court already plagued by questions of legitimacy. Coming under heavy fire from a major power could cripple the Court beyond repair, a fact which the Office of the Prosecutor would be hard pressed not to take into consideration when deciding whether to open even preliminary examination.

Financing provides another source of influence that threatens the Court’s impartiality. While the ICC requires cooperation to achieve its goals, it needs funding simply to exist. Because it is funded primarily by the States Parties using a U.N. formula that weights by financial ability, most of the Court’s funding comes from highly developed, mostly Western nations. Recent data shows as much as 60% of the Court’s funding comes from the European Union.31 And it is worth noting that the ICC has never taken on a case that defied the foreign policies of European states, instead focusing primarily on the former colonies of Africa.

The ICC’s apparent politicization has not only been noticed in Africa. Geis and Mundt said, “[T]he broad international consensus in favor of the Rome Statute has begun to fray as the court pursued justice in some of the worlds most politically-charged and complex crises, all of which happened to fall within Africa. At the same time, other states, such as Burma or North Korea, have so far eluded potential ICC investigations, most likely for geopolitical reasons and/or deference to regional interests.”32 Even Human Rights Watch, a strong supporter of the ICC, warned that “this unevenness increasingly poses a challenge to the credibility of international justice, and, in turn, to that of the ICC.”33

Conclusion

The ICC has taken a lot of criticism both from inside and outside of Africa regarding its performance since coming into force. Ultimately, whether the ICC has a parochial fixation on Africa or is simply too scared to pursue cases elsewhere is a distinction without significant difference. That the Court might shy away from pursuing particular cases for fear of backlash undermines its legitimacy no less than deliberately targeting a particular region. Both represent a politicization of justice.

The evidence also suggests that the ICC has little if any deterrent impact and often complicates efforts at conflict resolution. Combined with the Court’s significant procedural flaws and shortcomings – such as a reliance on a politicized Security Council, a need for extensive cooperation from nations with often conflicting agendas, and an apparent inability to accurately determine the basic facts of a case – it becomes harder and harder to justify the organization’s continued existence. It may simply be time to scrap the organization and radically rethink the goals and strategies used in pursuit of international justice.

Brian Garst is the Director of Policy and Communications for the Center for Freedom and Prosperity.

Endnotes

1. “Summary of Key Provisions of the ICC Statute,” Human Rights Watch, December 1, 1998. http://www.hrw.org/news/1998/12/01/summary-key-provisions-icc-statute.↩

2. “The International Criminal Court: Overview,” Amnesty International, accessed March 11, 2015, http://www.amnesty.ca/our-work/issues/international-justice/the-international-criminal-court.↩

3. Congressional Letter to President Clinton, December 15, 2000. http://www.amicc.org/docs/Congress12_00.pdf.↩

4. Gary Dempsey, “Pinochet’s Lessons,” Cato Institute, December 11, 1998. http://social.cato.org/publications/commentary/pinochets-lessons.↩

5. Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivkin, “The International Criminal Court vs. the American People,” The Heritage Foundation, Backgrounder #1249, February 5, 1999. http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/1999/02/the-international-criminal-court-vs-the-american-people; Ted Galen Carpenter, “No Civil Liberties At The International Criminal Court,” Cato Institute, December 27, 2000. http://social.cato.org/publications/commentary/no-civil-liberties-international-criminal-court.↩

6. See Thomas W. Jacobson, “8 Reasons the U.S.A. Should Not Participate in the International Criminal Court,” Focus on the Family, January 4, 2003. http://www.idppcenter.com/Intl_Criminal_Court-8_Reasons_USA_Should_Not_Join.pdf.↩

7. “The States Parties to the Rome Statute,” International Criminal Court, http://www.icc-cpi.int/en_menus/asp/states%20parties/ Pages/the%20states%20parties%20to%20the%20rome%20statute.aspx↩

8. UN General Assembly, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (last amended 2010), July 17, 1998. http://www.icc-cpi.int/nr/rdonlyres/ea9aeff7-5752-4f84-be94-0a655eb30e16/0/rome_statute_english.pdf.↩

9. Nancy A. Combs, Fact-Finding without Facts: The Uncertain Evidentiary Foundations of International Criminal Convictions (Cambridge U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2010).↩

10. Ibid.↩

11. “Witnesses before the International Criminal Court,” International Bar Association, July 2013, 14, http://www.ibanet.org/Document/Default.aspx?DocumentUid=9c4f533d-1927-421b-8c12-d41768ffc11f.↩

12. Ibid., 17.↩

13. See J. Michael Greig and James D. Meernik, “To Prosecute or Not to Prosecute: Civil War Mediation and International Criminal Justice,” International Negotiation 19, no. 2 (June 26, 2014): 257–84, doi:10.1163/15718069-12341278.↩

14. See Lyn S. Graybill, Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa: Miracle or Model? (Boulder, Colo: Lynne Rienner Pub, 2002).↩

15. Shawn Macomber, “Of Acquittals & Culpability: The ICC in Congo,” Lawfare Tyranny, March 2, 2015, http://www.lawfaretyranny.org/2015/03/02/ngudjolo-acquitted-icc/.↩

16. Ibid.↩

17. Brett D. Schaefer, “International Criminal Court Complicates Conflict Resolution in Libya,” WebMemo, Heritage Foundation, June 9, 2011. http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2011/06/international-criminal-court-complicates-conflict-resolution-in-libya.↩

18. Alex Spillius, “G8 summit: Russia agrees to mediate Gaddafi exit strategy,” Telegraph, May 27, 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/8542616/G8-summit-Russia-agrees-to-mediate-Gaddafi-exit-strategy.html↩

19. “Interview with Mr. Philippe Kirsch, President and Chief Judge of the ICC,” Citizens for Global Solutions.↩

20. See Geoff Dancy, Bridget Marchesi, Florencia Montal and Kathryn Sikkink, “The ICC’s deterrent impact – what the evidence show,” Open Democracy, February 3, 2015. https://www.opendemocracy.net/openglobalrights/geoff-dancy-bridget-marchesi-florencia-montal-kathryn-sikkink/icc%E2%80%99s-deterrent-impac.↩

21. See Frances Stewart, “Economic and Political Causes of Genocidal Violence: A comparison with findings on the causes of civil war.” MICROCON Research Working Paper 46, March 2011. http://www.microconflict.eu/publications/RWP46_FS.pdf.↩

22. Julian Ku and Jide Nzelibe, “Do International Criminal Tribunals deter or exacerbate humanitarian atrocities?, Washington University Law Review, Vol. 84, No. 4 (2006), p. 832.↩

23. Jacqueline Geis and Alex Mundt, “When to Indict? The Impact of Timing International Criminal Indictments on Peace Processes and Humanitarian Action”, the Brookings Institution-University of Bern Project on Internal Displacement, paper to the World Humanitarian Studies Conference, Groningen, Netherlands, February 2009, 18. http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2009/04/peace-and-justice-geis.↩

24. Aurelia Marina Pohrib, “Frustrating Noble Intentions,” International Community Law Review 15, no. 2 (January 1, 2013): 225–36.↩

25. United Nations, As General Assembly Takes up International Courts’ Annual Reports, Delegates Commend Contributions to Rule of Law, Debate Challenges Facing Mandates, October 30, 2014. http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/ga11576.doc.htm.↩

26. U.N., International Criminal Court Receives Mixed Performance Review, as General Assembly Concludes Discussion of Body’s Annual Report, October 31, 2014. http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/ga11577.doc.htm.↩

27. Decisions and Declarations. African Union, Extraordinary Session of the Assembly of the African Union October 12, 2013. http://www.au.int/en/sites/default/files/Ext%20Assembly%20AU%20Dec%20&%20Decl%20_E.pdf↩

28. “All Situations,” International Criminal Court. http://www.icc-cpi.int/en_menus/icc/situations%20and%20cases/situations/Pages/situations%20index.aspx↩

29. See “Statement by H.E. Mr. Kelebone A. Maope, Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Lesotho to the United Nations, On Behalf of African State Parties to the Rome Statute,” December 8, 2014 http://www.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/asp_docs/ASP13/GenDeba/ICC-ASP13-GenDeba-Lesotho-AfricanStatesParties-ENG.pdf.↩

30. “Nearly 60 states back referral of Syria conflict to ICC,” BBC, May 19, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27480970.↩

31. Mwangi S. Kimenyi, “Can the International Criminal Court Play Fair in Africa?” The Brookings Institution, October 17, 2013. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/africa-in-focus/posts/2013/10/17-africa-international-criminal-court-kimenyi.↩

32. Geis and Mundt, “When to Indict?” 18.↩

33. “Human Rights Watch Memorandum for the Eighth Session of the International Criminal Court Assembly of States Parties”, Human Rights Watch, November 9, 2009. http://www.hrw.org/news/2009/11/09/human-rights-watch-memorandum-eighth-session-international-criminal-court-assembly-s.↩