I wrote in May 2011 that the situation in Greece was hopeless because nobody with power and/or influence wanted the right policy.

So I wasn’t bashful about patting myself on the back later that year when it quickly became obvious that bailouts weren’t working.

Ever since then, I’ve tried to ignore the debacle, though I periodically succumb to temptation and highlight the wasteful stupidity of the Greek government.

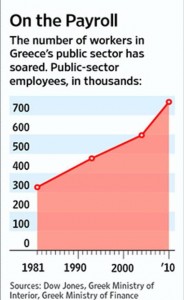

- Statism is so pervasive that Greece almost makes other European nations look like laissez-faire paradises by comparison.

- The country is a bureaucratic and regulatory nightmare.

- That destroys the dreams of entrepreneurs.

- With a costly Big Bird-style government-run media operation.

- And a never-ending array of new tax burdens.

- Bizarrely, Greece subsidizes pedophiles and requires…um…stool samples to set up online companies.

- But the most bizarre news of all is that the Greek government gets policy advice from people like Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz.

Having shared all sorts of bad news, I now feel obliged to point out that the situation isn’t hopeless.

Just last year, I explained that the right reforms could rescue Greece. And just in case you think I’m laughably naive, others have the same view.

Writing for the U.K.-based Telegraph, Ivan Mikloš, and Dalibor Roháč explain how Greece can enjoy and economic renaissance.

Greeks have to stop seeing themselves as victims… True, Greece’s international partners need to bear their share of responsibility for the economic catastrophe that has been unfolding in the country. However, it is not its creditors that are holding Greece back – rather, it is the lack of domestic leadership and ownership of economic reforms.

And what gives Mikloš and Roháč the credibility to make this assertion?

Simple, they’re from Slovakia and that nation faced a bigger mess after the collapse of the Soviet Empire and the peaceful breakup of Czechoslovakia.

As Slovaks, we have learned a fair bit about these matters. Once home to much of Czechoslovakia’s heavy industry – exporting arms and heavy machinery to the former Soviet bloc – Slovakia bore a disproportionate share of the costs incurred by the transition from communism in the early 1990s. …At the time of the country’s break-up, in 1992, the per capita income in Slovakia, expressed in purchasing power parity, was merely 62 per cent of that in the Czech Republic.The years that followed were not happy. The lingering sense of victimhood fostered nationalism and authoritarianism, as well as cronyism and corruption… By the time of the parliamentary election of 1998, Slovakia was on the brink of a financial meltdown.

But the election didn’t result in victory of crazed leftists, as we see with Syriza’s takeover in Greece.

Instead, the Slovak people elected reformers who decided to reduce the size and scope of the public sector.

The new government, formed by a coalition of pro-Western parties, restructured the banking sector, brought the public deficit under control… The parliamentary election of 2002 opened a unique window of opportunity. Slovakia’s novel tax reforms, spearheaded by domestic reformers under the auspices of Prime Minister Mikuláš Dzurinda, were seen by the IMF at the time as far too radical. However, the new, simpler, and leaner tax system, alongside other structural reforms, incentivized investment and turned Slovakia, nicknamed the “Tatra Tiger”, into the fastest-growing economy in the EU.

And a handful of other EU nations have followed the right path.

In 2008, instead of devaluing its currency – as recommended by the IMF – Latvia slashed public spending, cutting the salaries of civil servants by 26 per cent. The economy rebounded quickly to a growth rate of 5 per cent in 2011.

Here’s the bottom line.

Today, Slovakia’s per capita income rivals that of the Czech Republic. Together with Poland and the Baltic states, these countries have been catching up with their advanced Western European counterparts.

And the lesson for Greece should be clear, both politically and economically.

The purpose of economic reforms should not be to please the Troika, but to restore durable, shared prosperity. Deep, domestically led reforms need not be a form of political suicide, either. In 2006, after eight years of deep – and sometimes painful – reforms, Slovakia’s leading reformist party recorded its best electoral result in history. Similarly, many of the radical reformers in the Baltic states did well in subsequent elections. And a Greek leader who turns his country into a “Mediterranean Tiger” will most certainly not go down in infamy.

Unfortunately, the slim odds of good policy being adopted in Greece are partly the fault of the United States.

Or, to be more accurate, the Obama Administration is being very unhelpful by urging bailouts instead of reform.

Here’s some of what is being reported by the U.K.-based Guardian.

The Greek television channel, citing a senior German official, described the US treasury secretary, Jack Lew, imploring his German counterpart Wolfgang Schäuble to “support Greece” only to be told: “Give €50bn euro yourself to save Greece.” Mega’s Berlin-based correspondent told the station that the US official then said nothing “because, as is always the case according to German officials when it comes to the issue of money, the Americans never say anything”.

I’m not a big fan of Wolfgang Schäuble. The German Finance Minister is a strident opponent of tax competition, and some of his bad ideas are cited in the CF&P study that I wrote about yesterday.

But I greatly appreciate the fact that he basically told Obama’s corrupt Treasury Secretary to go jump in a lake.

And I’m also happy that Congress has done the right thing so that Obama and his team don’t have leeway to bail out Greece either directly or indirectly.