If you look at oil-rich jurisdictions around the world, it’s easy to see why experts sometimes write about the “resource curse.” Simply stated, governments don’t have much incentive to be responsible when they can use oil as a seemingly endless source of tax revenue.

From the perspective of voters, this seems like a good deal. They can get lots of goodies from government without themselves paying much tax.

This is definitely a good description of how fiscal policy operates in Alaska, a state I just visited to give a speech to the Alaska Alliance.

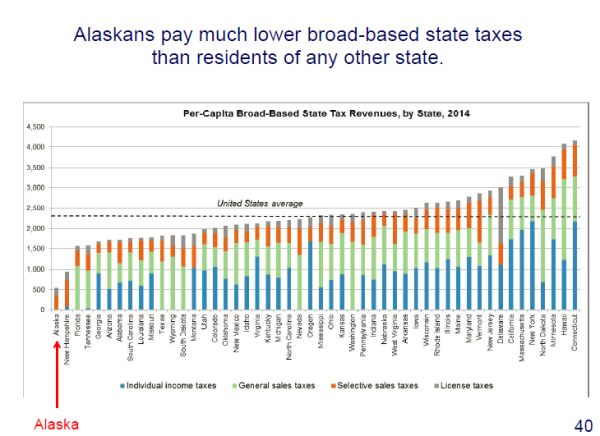

But everything I said during my remarks will be familiar to regular readers, so instead I want to share some state-specific information from a presentationearlier this year by Professor Gunnar Knapp of the University of Alaska Anchorage. As you can see from one of his charts, the tax burden on households is very low.

But the fact that households don’t pay much tax doesn’t mean the Alaska government is starved of money.

That’s because the state, on average, collects 90 percent of its revenue from severance taxes on natural resources.

And since there’s a lot of oil, that adds up to a lot of revenue. A lot.

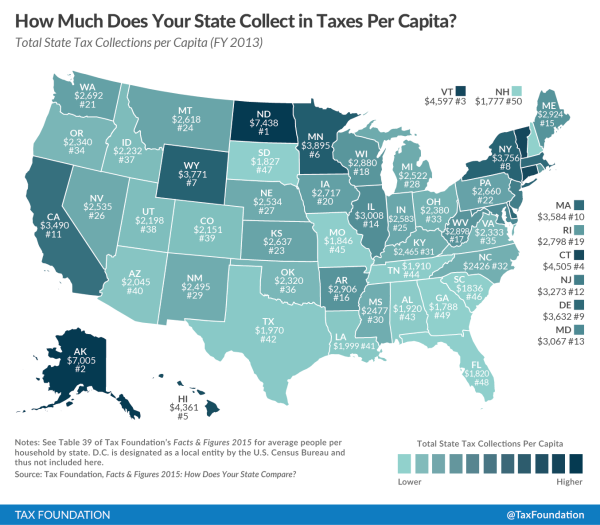

Here’s a map from the Tax Foundation, looking at per-capita state tax collections.

It turns out that Alaska is actually a very high-tax state, collecting more money than 48 other states. It’s just that one sector of the economy pays the overwhelming majority of that tax burden.

By the way, notice that oil-rich North Dakota has the highest tax burden and resource-rich Wyoming has the third-highest tax amount of tax revenue.

I suppose there’s some lesson to learn by comparing Alaska and Wyoming, which have lots of energy-related revenue and no state income taxes, with North Dakota, which has both.

But for purposes of today’s column, I want to emphasize a point about the boom-bust cycle and the value of spending caps.

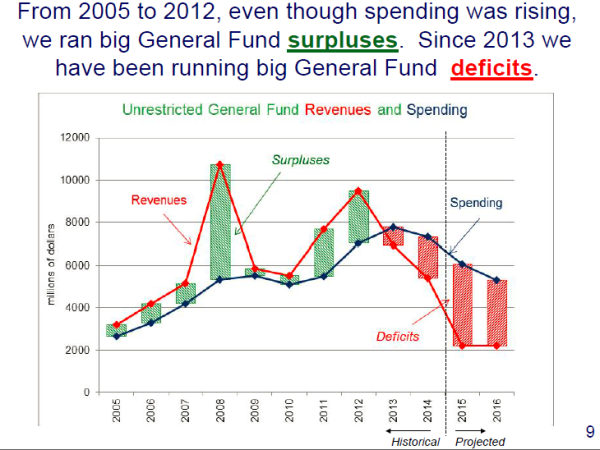

Let’s return to Professor Knapp’s presentation and peruse a chart showing spending, revenue, and fiscal balance from 2005-present. Knapp’s slide puts the focus on surpluses and deficits, but I want to draw your attention to the fact that spending (the blue line) basically tripled from 2005 to 2013.

In other words, politicians in Alaska were not followingMitchell’s Golden Rule, which would have required them to limit spending so that it grew slower than the private sector.

Instead, they responded to the influx of oil revenue during the boom years the same way alcoholics respond to an open bar. They had a spending orgy.

It’s no surprise that more revenue enabled more spending.

That’s why it’s a mistake to “feed the beast.”

But let’s focus on the fact that Alaska is now in the midst of fiscal turmoil and make the very simple point that some sort of spending cap, starting back in 2005, would have prevented the current crisis.

If spending was limited so that it grew by 2 percent annually, outlays today would only be about $500 million higher than they were in 2005. Given the plunge in oil-related revenue, even that might not have been enough to balance the budget for 2015 or 2016, but the state would have had plenty of money in the state’s rainy day funds (technically known as the “statutory budget reserve fund” and the “constitutional budget reserve fund”) to fill in the fiscal gap.

And this is why spending caps are so important. Governments get in trouble because politicians have a hard time resisting the urge to spend money during growth years, when plenty of tax revenue is being generated.

I’ve made this point when looking at data from California. It also applies when looking at the fiscal mess in Puerto Rico. And Greece.

But perhaps most relevant for Alaska, it’s exactly when happened in oil-rich Alberta. Politicians from a supposedly conservative party in that Canadian province also went on a spending binge when energy prices were high. But then oil prices dropped, energy-related tax collections fell, the ruling party was defeated at the polls, and a new leftist government has used the over-spending mess as an excuse to impose additional taxes.

Yet none of that would have happened if Alberta had a spending cap.

Just as the crisis in Alaska wouldn’t exist if there had been some mechanism to stop politicians in Juneau from over-spending.

Needless to say, there’s also a lesson here for Washington (one that actually was heeded between 2009-2014, but the real key is permanent, structural spending restraint).