During periods of economic weakness, governments often respond with “loose” monetary policy, which generally means that central banks will take actions that increase liquidity and artificially lower interest rates.

I’m not a big fan of this approach.

- If an economy is suffering from bad fiscal policy or bad regulatory policy,why expect that an easy-money policy will be effective?

- What if politicians use an easy-money policy as an excuse to postpone or avoid structural reforms that are needed to restore growth?

- And shouldn’t we worry that an easy-money policy will cause economic damage by triggering systemic price hikes or bubbles?

Defenders of central banks and easy money generally respond to such questions by assuring us that QE-type policies are not a substitute or replacement for other reforms.

And they tell us the downside risk is overstated because central bankers will have the wisdom to soak up excess liquidity at the right time and raise interest rates at the right moment.

I hope they’re right, but my gut instinct is to worry that central bankers are not sufficiently vigilant about the downside risks of easy-money policies.

But not all central bankers. While I was in London last week to give a presentation to the State of the Economy conference, I got to hear a speech byKristin Forbes, a member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.

She was refreshingly candid about the possible dangers of the easy-money approach, particularly with regards to artificially low interest rates.

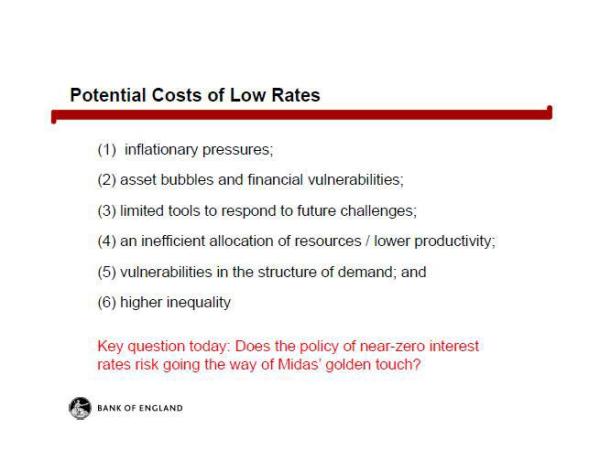

Here is one of the charts from her presentation.

Those of us who are old enough to remember the 1970s will be concerned about her first point. And this is important. It would be terrible to let the inflation genie out of the bottle, particularly since there may not be a Ronald Reagan-type leader in the future who will do what’s needed to solve such a mess.

But today I want to focus on her second, fourth, and fifth points.

So here are some of the details from her speech, starting with some analysis of the risk of bubbles.

…when interest rates are low, investors may “search for yield” and shift funds to riskier investments that are expected to earn a higher return – from equity markets to high-yield debt markets to emerging markets. This could drive up prices in these other markets and potentially create “bubbles”. This can not only lead to an inefficient allocation of capital, but leave certain investors with more risk than they appreciate. An adjustment in asset prices can bring about losses that are difficult to manage, especially if investments were supported by higher leverage possible due to low rates. If these losses were widespread across an economy, or affected systemically-important institutions, they could create substantial economic disruption. This tendency to assume greater risk when interest rates are low for a sustained period not only occurs for investors, but also within banks, corporations, and broader credit markets. Studies have shown that during periods of monetary expansion, banks tend to soften lending standards and experience an increase in their assessed “riskiness”. There is evidence that the longer an expansion lasts, the greater these effects. Companies also take advantage of periods of low borrowing costs to increase debt issuance. If this occurs during a period of low default rates – as in the past few years – this can further compress borrowing spreads and lead to levels of debt issuance that may be difficult to support when interest rates normalize. There is a lengthy academic literature showing that low interest rates often foster credit booms, an inefficient allocation of capital, banking collapses, and financial crises. This series of risks to the financial system from a period of low interest rates should be taken seriously and carefully monitored.

Her fourth and fifth points are particularly important since they show she appreciates the Austrian-school insight that bad monetary policy can distort market signals and lead to malinvestment.

Here’s some of what she shared about the fourth point.

…is there a chance that a prolonged period of near-zero interest rates is allowing less efficient companies to survive and curtailing the “creative destruction” that is critical to support productivity growth? Or even within existing, profitable companies – could a prolonged period of low borrowing costs reduce their incentive to carefully assess and evaluate investment projects – leading to a less efficient allocation of capital within companies? …For further evidence on this capital misallocation, one could estimate the rate of “scrappage” during the crisis and the level of capital relative to its optimal, steady-state level. Recent BoE work has found tentative evidence of a “capital overhang”, an excess of capital above that judged optimal given current conditions. Usually any such capital overhang falls quickly during a recession as inefficient factories and plants are shut down and new investment slows. The slower reallocation of capital since the crisis could partly be due to low interest rates.

And here is some of what she said about the fifth point.

A fifth possible cost of low interest rates is that it could shift the sources of demand in ways which make underlying growth less balanced, less resilient, and less sustainable. This could occur through increases in consumption and debt, and decreases in savings and possibly the current account. …if these shifts are too large – or vulnerabilities related to overconsumption, overborrowing, insufficient savings, or large current account deficits continue for too long – they could create economic challenges.

In her speech, Ms. Forbes understandably focused on the current environment and speculated about possible future risks.

But the concerns about easy-money policies are not just theoretical.

Let’s look at some new research from economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the University of California, and the University of Bonn.

In a study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, they look at the connections between monetary policy and housing bubbles.

How do monetary and credit conditions affect housing booms and busts? Do low interest rates cause households to lever up on mortgages and bid up house prices, thus increasing the risk of financial crisis? And what, if anything, should central banks do about it? Can policy directed at housing and credit conditions, with monetary or macroprudential tools, lead a central bank astray and dangerously deflect it from single- or dual-mandate goals?

It appears the answer is yes.

This paper analyzes the link between monetary conditions, credit growth, and house prices using data spanning 140 years of modern economic history across 14 advanced economies. …We make three core contributions. First, we discuss long-run trends in mortgage lending, home ownership, and house prices and show that the 20th century has indeed been an era of increasing “bets on the house.” …Second, turning to the cyclical fluctuations of lending and house prices we use novel instrumental variable local projection methods to show that throughout history loose monetary conditions were closely associated with an upsurge in real estate lending and house prices. …Third, we also expose a close link between mortgage credit and house price booms on the one hand, and financial crises on the other. Over the past 140 years of modern macroeconomic history, mortgage booms and house price bubbles have been closely associated with a higher likelihood of a financial crisis. This association is more noticeable in the post-WW2 era, which was marked by the democratization of leverage through housing finance.

So what’s the bottom line?

The long-run historical evidence uncovered in this study clearly suggests that central banks have reasons to worry about the side-effects of loose monetary conditions. During the 20th century, real estate lending became the dominant business model of banks. As a result, the effects that low interest rates have on mortgage borrowing, house prices and ultimately financial instability risks have become considerably stronger. …these historical insights suggest that the potentially destabilizing byproducts of easy money must be taken seriously

In other words, we’re still dealing with some of the fallout of a housing bubble/financial crisis caused in part by the Fed’s easy-money policy last decade.

Yet we have people in Washington who haven’t learned a thing and want to repeat the mistakes that created that mess.

Even though we now have good evidence about the downside risk of easy money and bubbles!

Sort of makes you wonder whether the End-the-Fed people have a good point.