I’m a huge fan of a simple and fair flat tax.

Simply stated, if we’re going to have some sort of broad-based tax, it makes sense to collect revenue in the least-damaging fashion possible.

And a flat tax achieves that goal by adhering to the principles of good tax policy.

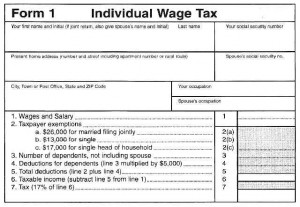

- A low tax rate – This is the best-known feature of the flat tax. A low tax rate is designed to minimize the penalty on work, entrepreneurship, and other forms of productive behavior.

- No double taxation of saving and investment – The flat tax gets rid of the tax bias against income that is saved and invested. The capital gains tax, double tax on dividends, and death tax are all abolished. Shifting to a system that taxes economic activity only one time will boost capital formation, thus facilitating an increase in productivity and wages.

- No distorting loopholes – With the exception of a family-based allowance designed to protect lower-income people, the flat tax eliminates all deductions, exemptions, shelters, preference, exclusions, and credits. By creating a neutral tax system, this ensures that decisions are made on the basis of economic fundamentals, not tax distortions.

All three features are equally important, sort of akin to the legs of a stool. And if we succeeded with fundamental reform, it would mean an end to the disgraceful internal revenue code.

But just because an idea is good policy doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s also good politics.

So let’s delve into the debate over whether the flat tax is a winning political issue as well as a pro-growth reform.

Writing for the Weekly Standard, Steve Moore of the Heritage Foundation thinks the flat tax has political legs.

…the flat tax is again the rage in a presidential primary. A number of GOP candidates, including Rand Paul, Rick Perry, Ted Cruz, and Scott Walker, are looking to go flat with a radically simplified postcard tax return. …Ripping up the 70,000-page tax code has visceral appeal to voters. …The way to sell the flat tax is as the ultimate Washington versus America issue. The only people who benefit from a complicated, barnacle-encrusted 70,000-page tax code are tax attorneys, accountants, lobbyists, IRS agents, and politicians who use the tax code as a way to buy and sell favors. The belly of the beast of corruption in American politics is the IRS tax code. The left keeps saying it wants to end the corrupting influence of big money in politics. Fine. By far the best way to do that is enact a flat tax and D.C. becomes the Sahara Desert.

I like what Steve is saying.

And I specifically agree that the best way of selling tax reform is to point out that it’s a Washington-versus-America issue.

When I first started giving speeches about the flat tax in the 1990s, I focused on the pro-growth and pro-competitive impact of lower marginal tax rates and reductions in double taxation.

I focused on the pro-growth and pro-competitive impact of lower marginal tax rates and reductions in double taxation.

People largely agreed with those points, but they didn’t get excited.

I soon learned that they instinctively liked the flat tax because they saw it as a way of cleaning out the stables of a corrupt system. In other words, they wanted tax reform mostly for reasons of fairness.

But with fairness properly defined, meaning all taxpayers playing by the same rules. Not the left’s definition, which is based on punishing success with high marginal tax rates.

Steve concurs.

So can the flat tax catch the populist tide of voter rage and angst over an economy that has squeezed the middle class for nearly a decade? Who knows? What seems certain is Democrats will run a class warfare campaign of raising tax rates on the rich. But envy isn’t an economic revival policy. Republicans can win this debate by going on the offensive and reminding voters that the best way to grow the economy, create jobs, and increase tax payments by the rich is to flatten the code. Flat is the new fair.

So does this mean the flat tax is a slam-dunk issue?

Ramesh Ponnuru of National Review is unconvinced. Here’s some of what he wrote about the candidates pushing fundamental reform.

They may have some creative ideas to get around problems with previous flat-tax proposals. But I have my doubts about whether a flat tax could be…as politically attractive as Moore suggests.

Ramesh is particularly skeptical whether the flat tax can be more appealing than the Lee-Rubio tax plan.

I have my doubts about whether a flat tax could be free from the objections Moore raises against Lee-Rubio… A 15 percent flat tax could also expose many more millions of people to tax increases than Lee-Rubio does; and it seems highly unlikely to reduce tax bills for as many people as Lee-Rubio does.

At the risk of sounding like a politician, I agree with both Steve and Ramesh.

Taking them in reverse order, Ramesh is correct that a flat tax faces an uphill battle. He specifically warns that a flat tax might result in higher fiscal burdens for millions of middle-class taxpayers.

Ultimately, that would depend on the tax rate, the size of the family-based allowance, and whether tax reform also was a tax cut. And those choices could be easier to make if Republicans actually demonstrated some political acumen and modernized the revenue-estimating system at the Joint Committee on Taxation.

And Ramesh also points out, quite appropriately, that the flat tax will create strong opposition from interest groups that benefit from provisions in the current system.

But Steve is correct that people want bold reform, which is a proxy for ending tax-code corruption. I’ve already praised the Lee-Rubio plan, which Ramesh likes, but I have a hard time imagining that such a plan will seize the public imagination like a flat tax.

Moreover, the Lee-Rubio plan is a huge tax cut. Since I think good reform is more likely if a plan lowers the overall tax burden, I consider that to be a feature rather than a bug.

But it does mean you have to fight a two-front war, battling both those who benefit from the current system as well as those who don’t want to reduce the flow of revenue to Washington.

These are big obstacles, whether we’re talking about an incremental plan like Lee-Rubio or big-picture reform like a flat tax.

Which is why, regardless of what happens with elections, I’m not overly optimistic about making progress. Unless, of course, we figure out some way of dealing the growing burden of federal spending. Which necessarily requires genuine entitlement reform.