When I wrote the other day that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development was the worst international bureaucracy, I must have caused some envy at the International Monetary Fund.

One can imagine the tax-free bureaucrats from the IMF, lounging at their lavish headquarters, muttering “Mitchell obviously hasn’t paid enough attention to our work.”

And they may be right. The IMF has published some new research on inequality and growth that merits our attention. I hoped it would be a good contribution to the discussion, but I was disappointed (albeit not overly surprised) to see that the authors put ideology over analysis.

Widening income inequality is the defining challenge of our time. …Equality, like fairness, is an important value.

Needless to say, they never explain why inequality is a more important challenge than anemic growth.

Moreover, they never differentiate between bad Greek-style inequality that iscaused by cronyism and good Hong Kong-style inequality that is caused bysome people getting richer faster than other people getting richer in a free market.

And they certainly don’t define “fairness” in an adequate fashion.

But let’s not get hung up on the rhetoric. The most newsworthy part of the study is that these IMF bureaucrats produced numbers ostensibly showing that growth improves if more income goes to those at the bottom 20 percent.

…we find an inverse relationship between the income share accruing to the rich (top 20 percent) and economic growth. If the income share of the top 20 percent increases by 1 percentage point, GDP growth is actually 0.08 percentage point lower in the following five years, suggesting that the benefits do not trickle down. Instead, a similar increase in the income share of the bottom 20 percent (the poor) is associated with 0.38 percentage point higher growth.

And this correlation leads them to make a very bold assertion.

…there does not need to be a stark efficiency-equity tradeoff. Redistribution through the tax and transfer system is found to be positively related to growth for most countries.

Followed by some policy suggestions for more class-warfare tax policy to finance additional redistribution.

…the redistributive role of fiscal policy could be reinforced by greater reliance on wealth and property taxes, more progressive income taxation… In addition, reducing tax expenditures that benefit high-income groups most and removing tax relief—such as reduced taxation of capital gains, stock options, and carried interest—would increase equity.

Those are some bold leaps in logic that the authors make. And we’ll look at some new, high-quality research on the efficiency-equity tradeoff below, but first let’s consider the IMF’s supposed empirical findings on growth and income.

Several questions spring to mind:

- Did they cherry pick the data? Why look at the relationship between growth and income gains in the previous five years rather than one year, three yeas, or ten years?

- Why do they assume the correlation they found in the five-year data somehow implies causation for future growth? Roosters crow before the sun comes up, after all, but they don’t cause sunrises.

- Was there any attempt to look at other hypotheses? One thing that instantly came to my mind was the possibility that recessions often are preceded by easy-money policies that create asset bubbles. And since those asset bubbles tend to artificially enrich savers and investors with higher incomes, perhaps that explains the correlation in the IMF’s data.

- Perhaps most important, why assume that faster income growth for the bottom 20 percent automatically means there should be more redistribution through the tax and transfer system? Maybe that income growth is the natural – and desirable – outcome of good Hong Kong-type policies?

There are all sorts of other questions that could and should be asked, but let’s now shift to the IMF’s bold assertion that their ostensible correlation somehow proves that there’s no tradeoff between growth (efficiency) and redistribution (equity).

Kevin Hassett of the American Enterprise Institute investigated the degree to which Arthur Okun was right about a tradeoff between growth and redistribution.

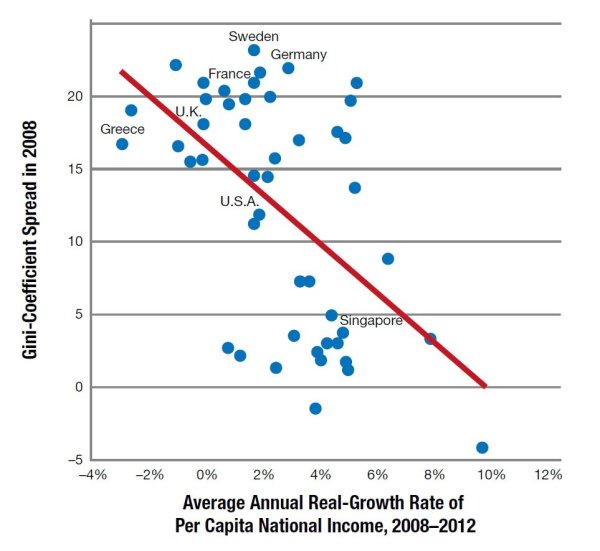

Forty years ago, the economist Arthur Okun wrote a seminal book with a self-explanatory title: Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff. …Okun’s tradeoff seems to be forgotten by many on the left, who advocate expanded government spending at every turn… What is needed is some kind of controlled experiment.. When the financial crisis began, countries varied tremendously in the extent to which they redistributed income. Some, such as Ireland and Sweden, redistributed a lot; others, such as the U.S. and Switzerland, not so much. Now, seven years later, some countries have recovered smartly. Others have not. If we go back and sort countries by how much they redistributed before the crisis, how does the growth experience compare? …The vertical axis plots how much redistribution there was in each country in 2008. The horizontal axis plots the rate of per capita national-income growth that each country averaged during the four years between 2008 and 2012. In some sense, then, the chart asks the question, “To what extent does variation in the size of the welfare state in 2008 explain variation in how economies recovered from the crisis between 2008 and 2012?” …As one can see in the chart, …the data show a clear pattern: the heavy redistributors have done much worse.

And here’s Kevin’s chart, and it clearly shows the redistribution-oriented nations had relatively slow growth (the top left of the chart).

The bottom line is that Kevin’s hypothesis and data are much more compelling that the junky analysis from the IMF.

But you don’t need to be an expert in economic jargon or statistical analysis to reach that conclusion.

Just look around the globe. The real-world evidence is so strong that only an international bureaucrat could miss it. The nations that follow the IMF’s advice, with lots of redistribution and class-warfare taxation, are the ones that languish.

After all, Greece, Italy, and France are not exactly role models.

While jurisdictions such as Hong Kong and Singapore routinely set the standard for growth.

And nations with medium-sized welfare states, such as Switzerland, Australia, and the United States, tend to fall in the middle. We out-perform Europe’s big-government economies, but we lag behind the small-government economies.

Let’s close by looking at some additional findings from the IMF study.

I was actually surprised to see that the bureaucrats admitted that inequality (more properly defined as some people getting richer faster than others get richer) was the natural result of positive economic developments.

We find that less-regulated labor markets, financial deepening, and technological progress largely explain the rise in market income inequality in our full sample over the last 30 years.

So why, then, is “inequality” a “defining challenge”?

Needless to say, the IMF never gives us a good answer.

I also was struck by this passage from the IMF study.

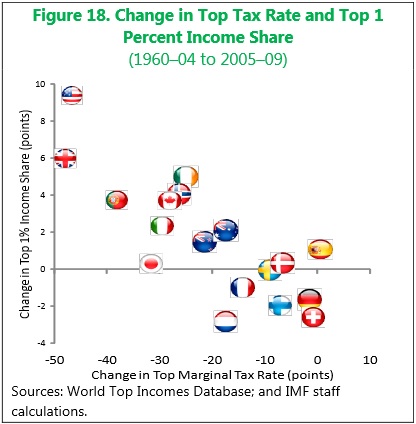

Figure 18 indicates that rising pre-tax income concentration at the top of the distribution in many advanced economies has also coincided with declining top marginal tax rates (from 59 percent in 1980 to 30 percent in 2009).

And here is the chart, which the IMF would like you to believe is evidence that lower tax rates have contributed to inequality (even though the bureaucrats already admitted that natural forces have led some to get richer faster than others).

Yet this chart simply shows that supply-siders were right. Reagan, Kemp, and other tax cutters argued that lower tax rates would lead rich people to earn – and declare – more taxable income.

And that’s exactly what happened!

Heck, I’ve already shared incredibly powerful data from the IRS on this occurring during the 1980s in the United States, so it’s no surprise it happened in other nations as well.

But I don’t want to be reflexively critical of the IMF. The study did have some useful data.

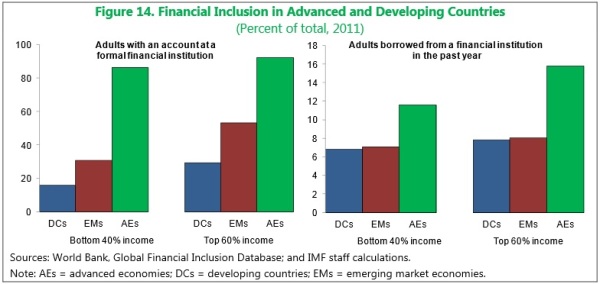

And there was even one very good recommendation for helping the poor by cutting back on misguided anti-money laundering laws.

Country experiences also suggest that policies such as granting exemptions from onerous documentation requirements, requiring banks to offer basic accounts, and allowing correspondent banking are useful in fostering inclusion.

Since I’ve written that anti-money laundering laws are ineffective at fighting crime while putting costly burdens on those with low incomes, I’m glad to see the IMF has reached the same conclusion.

And here’s a chart from the IMF study showing how poor people are less likely to have accounts at financial institutions.

By the way, the World Bank has produced some very good research on how the poor are hurt by inane anti-money laundering rules.

So kudos to some international bureaucracies for at least being sensible on that issue.

But speaking of international bureaucracies, I started this column by joking about the contest to see which one produced the worst research with the worst recommendations.

And while the IMF’s new inequality study definitely deserves to be mocked, I must say that it’s not nearly as bad as the drivel that was published by the OECD.

So our friends in Paris can rest on their laurels, confident that they do the best job of squandering American tax dollars.