I’ve written many times about the shortcomings of government schools at the K-12 level. We spend more on our kids than any other nation, yet our test scores are comparatively dismal.

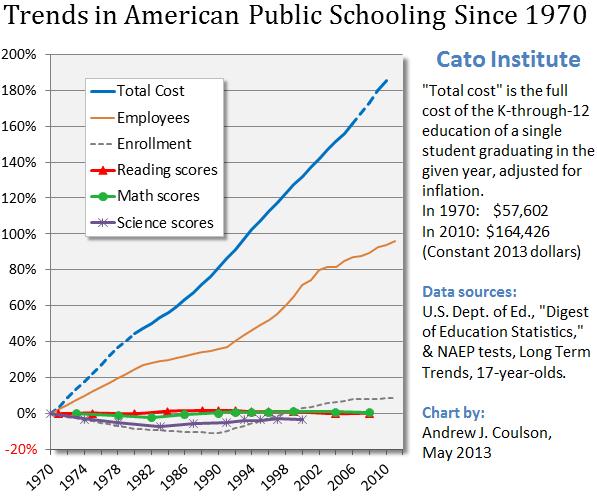

And one of my points, based on this very sobering chart from the Cato Institute’s Andrew Coulson, is that America’s educational performance took a turn in the wrong direction when the federal government became more involved starting about 40-50 years ago.

And one of my points, based on this very sobering chart from the Cato Institute’s Andrew Coulson, is that America’s educational performance took a turn in the wrong direction when the federal government became more involved starting about 40-50 years ago.

Well, the same unhappy story exists in the higher-education sector. Simply stated, there’s been an explosion of spending, much of it from Washington, yet the rate of return appears to be negative.

Let’s take a closer look at this issue.

Writing for the New York Times, Professor Paul Campos of the University of Colorado begins his column by giving the conventional-wisdom explanation of why it costs so much to go to college.

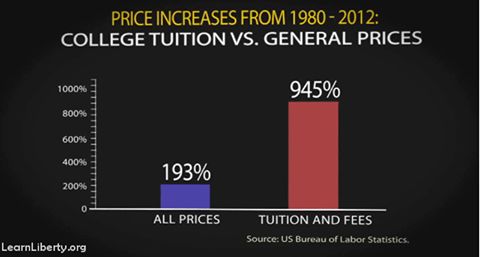

Once upon a time in America, baby boomers paid for college with the money they made from their summer jobs. Then, over the course of the next few decades, public funding for higher education was slashed. These radical cuts forced universities to raise tuition year after year, which in turn forced the millennial generation to take on crushing educational debt loads, and everyone lived unhappily ever after. This is the story college administrators like to tell when they’re asked to explain why, over the past 35 years, college tuition at public universities has nearly quadrupled, to $9,139 in 2014 dollars.

That’s a compelling story, and it surely has convinced a lot of people, but it has one tiny little problem. It’s utter nonsense.

That’s a compelling story, and it surely has convinced a lot of people, but it has one tiny little problem. It’s utter nonsense.

It is a fairy tale in the worst sense, in that it is not merely false, but rather almost the inverse of the truth. …In fact, public investment in higher education in America is vastly larger today, in inflation-adjusted dollars, than it was during the supposed golden age of public funding in the 1960s. Such spending has increased at a much faster rate than government spending in general. For example, the military’s budget is about 1.8 times higher today than it was in 1960, while legislative appropriations to higher education are more than 10 times higher. In other words, far from being caused by funding cuts, the astonishing rise in college tuition correlates closely with a huge increase in public subsidies for higher education. If over the past three decades car prices had gone up as fast as tuition, the average new car would cost more than $80,000.

Unfortunately, little of this money is being used for education.

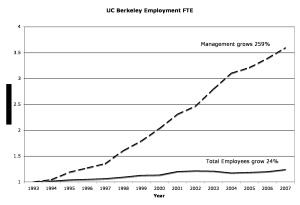

…a major factor driving increasing costs is the constant expansion of university administration. According to the Department of Education data, administrative positions at colleges and universities grew by 60 percent between 1993 and 2009, which Bloomberg reported was 10 times the rate of growth of tenured faculty positions. Even more strikingly, an analysis by a professor at California Polytechnic University, Pomona, found that, while the total number of full-time faculty members in the C.S.U. system grew from 11,614 to 12,019 between 1975 and 2008, the total number of administrators grew from 3,800 to 12,183 — a 221 percent increase.

This is great news, but only if you’re a bureaucrat.

But if you think education dollars should be used to educate, it’s not very encouraging.

For example, check out this very depressing example of bureaucratic bloat at the University of California San Diego.

Now let’s zoom back out to the bigger issue. Professor Richard Vedder from Ohio University is even more critical of handouts for the higher-education sector. Here’s some of what he wrote for National Review.

America’s colleges and universities are terribly inefficient and excessively expensive, foster relatively little learning and ability to think critically, and turn out too many graduates who end up underemployed. These and related problems have grown sharply in the half century since the Higher Education Act of 1965 heralded a major expansion of the federal role in higher education.

Rich correctly points out that the federal government has made matters worse.

Rich correctly points out that the federal government has made matters worse.

Washington is far more the problem than the solution to the current afflictions of American higher education. …Tuition has skyrocketed in the era since federal student-loan and grant programs started to become large in the late 1970s. Colleges have effectively confiscated federal loan and grant money designated for students and used it to help fund an academic arms race that has given us climbing walls, lazy rivers, and million-dollar university presidents — but declining literacy among college students and a massive mismatch between students’ labor-market expectations and the realities of the job market.

And you won’t be surprised to learn that federal handouts have backfired against low-income students.

…the primary goal of the federal student-aid programs was to improve access to college for lower-income persons. Here, the record is one of total failure: A smaller percentage of recent college graduates come from the bottom quartile of the income distribution today than was the case in 1970, when federal student-assistance programs were in their infancy.

To close on a semi-optimistic note, Prof. Vedder highlights some intriguing incremental reforms advanced by Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, including the notion that handouts should be linked to performance.

…he seems to embrace the idea that colleges should have “skin in the game”: They should face financial consequences for admitting, and then failing to graduate, students who default on loans and have marginal educational backgrounds indicating that they were clearly ill prepared for truly higher education. …Users and providers of university services need to feel the pain associated with academic non-performance. Growing federal involvement in higher education has brought rising prices, falling quality, and student underemployment. While it is perhaps politically impossible to radically change the federal student financial-aid programs now, the Alexander move is an important first step to rethinking how we finance higher education.

Ultimately, though, we won’t solve the problem unless the federal government’s role is abolished, which is yet another reason to shut down the Department of Education in Washington.