Here we go again.

The politicians in Washington are whining and complaining that “evil” and “greedy” corporations are bring traitors by engaging in corporate inversions so they can leave America.

The issue is very simple. The United States has a very unfriendly and anti-competitive tax system. So it’s very much in the interest of multinational companies to figure out some way of switching their legal domicile to a jurisdiction with better tax law. There are two things to understand.

First, the United States has the world’s highest corporate tax rate, which undermines job creation and competitiveness in America, regardless of whether there are inversions.

Second, the United States has the most punitive “worldwide” tax system, meaning the IRS gets to tax American-domiciled companies on income that is earned (and already subject to tax) in other nations.

Unfortunately, the White House has no desire to address these problems.

This means American companies that compete in global markets are in an untenable position. If they’re passive, they’ll lose market share and be less able to compete.

And this is why so many of them have decided to re-domicile, notwithstanding childish hostility from Washington.

The Wall Street Journal is reporting, for instance, that the long-rumored inversion of Pfizer is moving forward.

Pfizer Inc. and Allergan PLC agreed on a historic merger deal worth more than $150 billion that would create the world’s biggest drug maker and move one of the top names in corporate America to a foreign country. …The takeover would be the largest so-called inversion ever. Such deals enable a U.S. company to move abroad and take advantage of a lower corporate tax rate elsewhere… In hooking up with Allergan, Pfizer would lower its tax rate below 20%, analysts estimate. Allergan, itself the product of a tax-lowering inversion deal, has a roughly 15% tax rate.

While there presumably will be some business synergies that will be achieved, tax policy played a big role. Here are some passages from a WSJ story late last month.

Pfizer Inc. Chief Executive Ian Read said Thursday he won’t let potential political fallout deter him from pursuing a tax-reducing takeover that could move the company’s legal address outside the U.S… Mr. Read…said he had a duty to increase or defend the value of his company, which he said is disadvantaged by the U.S. tax system.

And the report accurately noted that the United States has a corporate tax system that is needlessly and destructively punitive.

The U.S. has the highest corporate tax rate—35% — in the industrialized world, and companies owe taxes on all the income they earn around the world, though they can defer U.S. taxes on foreign income until they bring the money home. In other countries, companies face lower tax rates and few if any residual taxes on moving profits across borders.

And when I said America’s tax system was “needlessly and destructively punitive,” that wasn’t just empty rhetoric.

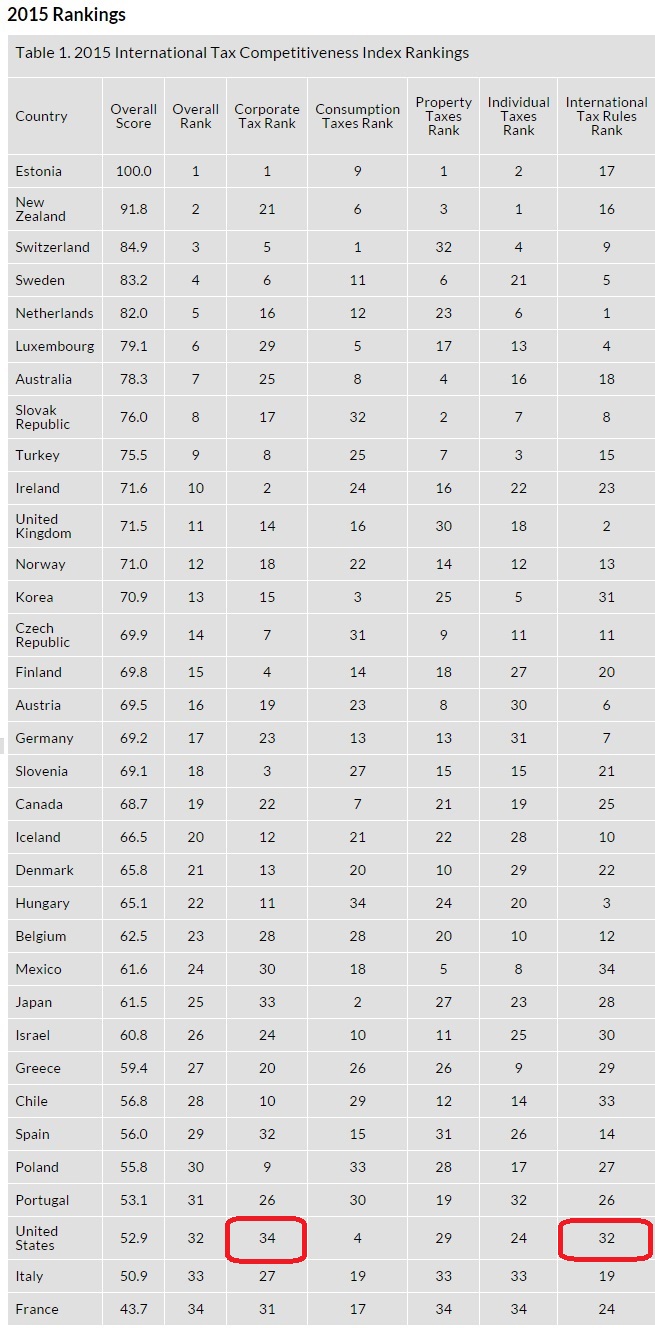

The Tax Foundation has an International Tax Competitiveness Index, which ranks the tax systems of industrialized nations. As you can see, America does get a good grade.

The United States places 32nd out of the 34 OECD countries on the ITCI. There are three main drivers behind the U.S.’s low score. First, it has the highest corporate income tax rate in the OECD at 39 percent (combined marginal federal and state rates). Second, it is one of the few countries in the OECD that does not have a territorial tax system, which would exempt foreign profits earned by domestic corporations from domestic taxation. Finally, the United States loses points for having a relatively high, progressive individual income tax (combined top rate of 48.6 percent) that taxes both dividends and capital gains, albeit at a reduced rate.

Here’s the table showing overall scores and ranking for major categories.

You’ll have to scroll to the bottom portion to find the United States. And I’ve circled (in red) America’s ranking for corporate taxation and international tax rules. So perhaps it’s now easy to understand why Pfizer will be domiciled in Ireland.

y the way, while I’m a huge admirer of the Tax Foundation, I don’t fully agree with this ranking because there’s no component score for aggregate tax burden.

I don’t say that because it would boost America’s score (though that would help bump up the United States), but rather because I think it’s important to have some measure showing the degree to which resources are being diverted from the economy’s productive sector to government.

But I’m digressing. Let’s now return to the main issue of Pfizer and corporate inversions.

Our friends on the left have a blame-the-victim approach to this issue. Here’s what the Wall Street Journal wrote in September, before the Pfizer-Allergan merger.

Remember last year when the Obama Treasury bypassed federal rule-making procedures to stop U.S. companies from moving overseas? It didn’t work. …Watching U.S. firms skedaddle, President Obama might have thought that perhaps the U.S. should stop taxing earnings generated outside its borders, since almost no one else on the planet does. Or he might have pondered whether the industrialized world’s highest corporate income tax rate is good for business. Being Barack Obama, the President naturally sought to bar companies from leaving. And his Treasury, being part of the Obama Administration, naturally skipped the normal process of proposing new rules and allowing the public to comment on them.

But even this lawless administration hasn’t been able to block inversions by regulatory edict.

…in the year since the Treasury Department “tightened its rules to reduce the tax benefits of such deals, six U.S. companies have struck inversions, compared with the nine that did so the year before.” Meanwhile, foreign takeovers of U.S. firms, which have the same effect of preventing the IRS from capturing world-wide earnings, are booming. These acquisitions exceed $379 billion so far this year, …far above any recent year before Treasury acted against inversions. So the policy won’t generate the revenue that Mr. Obama wants to collect, but it is succeeding in moving control of U.S. businesses offshore.

This should be an argument for a different approach, but Obama is too ideological to compromise on this issue.

And his leftist allies also don’t seem open to reason. Here’s some of what Jared Bernstein wrote a couple of days ago for the Washington Post.

There are three parts of his column that cry out for attention. First, he gives away his real motive by arguing that Washington should have more money.

…an eroding tax base is a bad thing. …we will need more, not less, revenue in the future.

In the context of inversions, he’s saying that it’s better for politicians to seize business earnings rather than to leave the funds in the private sector.

He then makes two assertions that simply are either untrue or misleading.

For instance, he puts forth an Elizabeth Warren-type argument that firms that engage in inversions are dodging their obligation to “contribute” to the system that allows them to earn money.

…the main thing the inverting company changes here is its tax mailbox and thus where it books its profits, not its actual location. So it’s still taking advantage of our infrastructure, our markets, and our educated workforce — it’s just significantly cutting what it contributes to them.

Utter nonsense. Every inverted company (and every foreign company of any kind) pays tax to the IRS on income earned in the United States.

All that happens with an inversion is that a company no longer pays tax to the IRS on income that is earned in other nations (and already subject to tax by governments in those nations!).

But that’s income that the United States shouldn’t be taxing in the first place.

Jared than argues that America’s corporate tax rate isn’t very high if you look at average tax rates.

…isn’t the problem that when it comes to corporate taxes, we’re the high-tax country? Not really. Our statutory corporate tax rate (35 percent) may be higher than that in many other countries, but because of all these tax avoidance schemes, the effective corporate rate is closer to 20 percent.

Once again, he’s off base. What matters most from an economic perspective is the marginal tax rate. Because that 35 percent marginal rate is what impacts incentives to earn more income, create more jobs, and expand investments.

And that marginal tax rate is what’s important for purposes of a company competing with a foreign competitor.

Here’s a briefing I gave to Capitol Hill staffers last year. The issues haven’t changed, so it’s still very appropriate for today’s debate.

Now perhaps you’ll understand why I’m a big fan of this poster.