What’s the most effective way of screwing up a sector of the economy? Since I’m a fiscal policy economist, I’m tempted to say that bad tax policy is the fastest way of causing damage. And France might be my top example.

But other forms of government intervention also can have a poisonous effect. Regulation, for instance, imposes an enormous burden on our economy.

Today, though, we’re going to look at how subsidies can result in costly distortions. More specifically, using examples from the health sector and higher-ed sectors, we’re going to see how “third-party payer” is a very expensive form of intervention.

We’ll start with the example from the healthcare sector. Writing for the Institute for Policy Innovation, Merrill Matthews has a must-read article about an unintended consequences of Obamacare.

He starts with a very sensible point about the effect of third-party payer.

Health care actuaries will tell you that when people have to spend more out of pocket for health care, they tend to spend less. And when a third party—employers, health insurers or the government—insulates consumers from the cost of care they tend to spend more. Just imagine how much more people would spend on cars if they could have any car they wanted for a $20 copay.

The car-buying example is great. I’ve previously tried to make the same point about third-party payer by using the examples of home insurance and car insurance, but I may have to steal Merrill’s argument since it’s so intuitively effective.

But that’s a digression. Merrill has a far more important point about what’s actually happening today in the health care sector.

…out-of-pocket spending on health care has declined for decades—until the Affordable Care Act kicked in. In 1961, Americans forked over 43 cents out of their own pocket for every dollar spent on health care. That out-of-pocket spending steadily declined over the years so that by 2010 consumers were only spending about 12 cents out of pocket. …Enter Obamacare in 2010. By 2012 out-of-pocket spending had risen to 14.8 percent of total health care spending, and by 2013 it was up to 15.2 percent, according to the Health Care Cost Institute. With people spending more out of pocket, they will naturally curb their spending. And expect to be spending more out of pocket in the future. That’s in part because so many Americans have had to shift to very high deductible policies in order to afford Obamacare’s very expensive coverage. Thank you, President Obama! …The upshot of these higher deductibles is that people will spend less on health care, and that is helping to slow the growth in health care spending—giving Obama his boasting point. Rising deductibles aren’t the only factor, but they are an important one.

Yet Obama doesn’t really deserve to boast.

But here’s the irony: Obama never intended any of this. He thought Obamacare would reduce out-of-pocket spending. And he and most Democrats have railed against high-deductible policies for years, claiming that greedy health insurers were taking people’s money but didn’t have to pay any claims (because of the high deductibles). And yet under Obamacare deductibles have never been so high. The fact is that moving to higher deductibles, especially when accompanied by a tax-free health care spending account for smaller and routine expenditures, is good policy.

And let’s not forget that Obama’s “Cadillac tax” on employer-provided health insurance also is good policy (though it was implemented the wrong way).

So maybe, as that policy also takes effect, we’ll get even further reductions over time in third-party payer!

Which might cause me adjust my overall assessment of Obamacare. In the past, I’ve said it was awful policy because it expanded the Medicaid entitlement while also mucking up the private insurance market.

All that’s still true, but we’re getting some unintended consequences that are positive. Not only are some states refusing to expand Medicaid, but Merrill’s big point is that the private insurance market is evolving in ways that have some good effects.

So maybe instead of Obamacare shifting us from a 68-percent-government-controlled healthcare system to one where government has 79-percent control, as I speculated back in 2013, maybe we’ll wind up with a system that’s “only” 73-percent dictated by government.

Not a victory, to be sure, but at least we’re going in the wrong direction at a slower pace.

Now let’s shift to the higher-ed sector.

Paul Campos, a law professor at the University of Colorado, writes in The Atlantic about the surging level of subsidies for higher education.

…when considering government support for American higher education as a whole, subsidies for colleges and universities are—even on a per-student basis and despite the enrollment explosion—greater than ever before. In particular, per-capita government subsidies are far higher now than they were 35 years ago, when tuition was drastically lower. …The federal government is currently spending approximately $80 billion per year on subsidies for higher education—a figure that almost exactly matches the combined higher-ed spending of the 50 legislatures. …The Pell grant program has expanded rapidly, more than tripling in size since 2000. …What’s far less known…is the remarkable extent to which the federal tax code has been amended in ways that benefit colleges and universities. According to the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation’s most recent estimates of federal tax expenditures, the IRS is currently redistributing approximately $45.7 billion annually in tax revenue in ways that directly and indirectly support American higher education. (This represents a 675 percent increase in such spending since 1990.)

Even though I agree with his analysis, I get agitated when tax preferences are referred to as “spending.”

But that’s not particularly relevant today. What matters is that there’s been an unbroken increase in handouts and subsidies for the higher-ed sector over the past few decades.

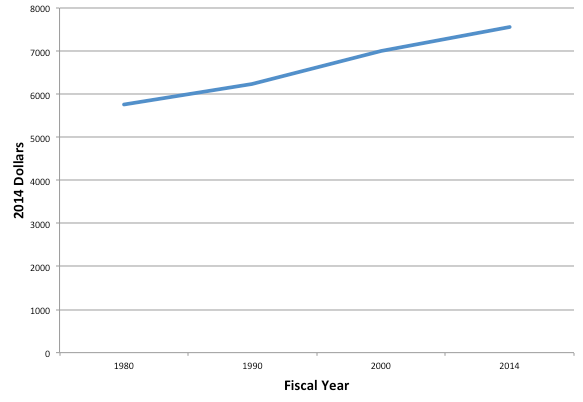

Here’s a chart from his article.

Now let’s look at the policy implications. Mr. Campos outlines a series of problems in the higher-education sector.

…total per-student government support for higher education has increased. Yet this increase has failed to stop or even slow massive tuition increases at both public and private schools. …many higher-ed institutions have become increasingly bloated and inefficient—even as they’ve relied on a growing population of poorly paid contingent faculty members and on hundreds of billions of dollars of federal student loans, only a small percentage of which are currently being repaid in a timely manner. …roughly half of recent college graduates in the U.S. find themselves either unemployed or seriously underemployed. And many graduates struggle to pay educational debts that, unlike almost all other debts in American society, typically can’t be settled via bankruptcy.

But he doesn’t really connect the dots, other than to point out that it is absurdly dishonest when some people (like Senator Bernie Sanders) want others to believe that we need even more intervention and more handouts to compensate for non-existent budget cuts.

Claiming that skyrocketing tuition has been caused by “cuts” in government subsidies only helps delay American higher education’s inevitable day of fiscal reckoning.

If he did connect the dots, he would have explained that the higher-ed sector is needlessly expensive and pointlessly inefficient because of all the subsidies from government.

He may even agree with that assessment, though he isn’t explicit about the connection. Though Professor Richard Vedder doesn’t hesitate in pointing outthat bad government policy deserves the blame.

And if you want to learn more, here’s a great video from Learn Liberty explaining why subsidies have translated into higher tuition.

Last but not least, here’s my two cents on the issue, including my dour prediction that the higher-ed bubble won’t pop until and unless we stop the handouts from government.

Yet another reason why we should dismantle the Department of Education.