In conversations with statists, I’ve learned that many of them actually believe the economy is a fixed pie. This misconception leads them to think that rich people get rich only by somehow making others poor.

In this simplistic worldview, a bigger slice for one person means less for everyone else.

In reality, though, their fixation on the distribution of income leads them to support policies that hinder growth.

And here’s the ironic part. When you have statist policies such as high taxes and lots of redistribution, the economy weakens and the result is a stagnant pie.

In other words, the zero-sum society they fear only occurs when their policies are in effect!

To improve their understanding (and hopefully to make my leftist friends more amenable to good policy ideas), I oftentimes share two incontestable facts based on very hard data.

1. Per-capita economic output has increased in the world (and in the United States), which obviously means that the vast majority of people are far better off than their ancestors.

2. There are many real-world examples of how nations with sensible public policy enjoy very strong growth, leading to huge increases in living standards in relatively short periods of time.

I think this is all the evidence one needs to conclude that free markets and small government are the right recipe for a just and prosperous society.

But lots of statists are still reluctant to change their minds, even if you get them to admit that it’s possible to make the economic pie bigger.

I suspect in many cases their resistance is because (at least subconsciously) they resent the rich more than they want to help the poor. That’s certainly the conclusion that Margaret Thatcher reached after her years in public life.

So, in hopes of dealing with this mindset, let’s augment the two points listed above.

3. There is considerable income mobility in the United States, which means today’s rich and today’s poor won’t necessarily be tomorrow’s rich and tomorrow’s poor.

Let’s look at some evidence for this assertion.

And we’ll start with businesses. Here’s what Mark Perry of the American Enterprise Institute found when he investigated changes in the Fortune 500.

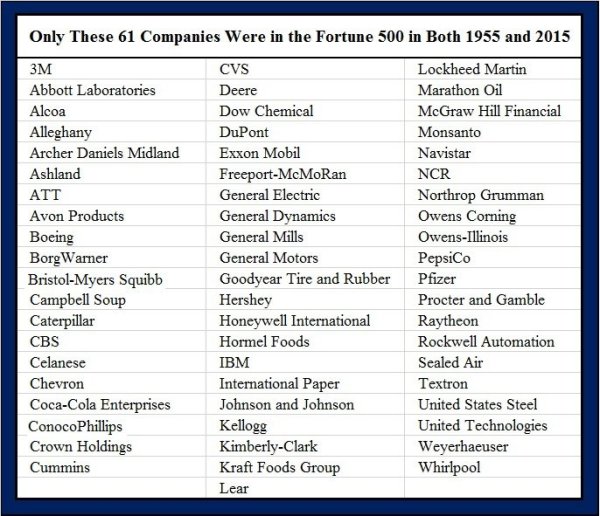

Comparing the 1955 Fortune 500 companies to the 2015 Fortune 500, there are only 61 companies that appear in both lists… In other words, only 12.2% of the Fortune 500 companies in 1955 were still on the list 60 years later in 2015… The fact that nearly 9 of every ten Fortune 500 companies in 1955 are gone, merged, or contracted demonstrates that there’s been a lot of market disruption, churning, and Schumpeterian creative destruction… The constant turnover in the Fortune 500 is a positive sign of the dynamism and innovation that characterizes a vibrant consumer-oriented market economy, and that dynamic turnover is speeding up in today’s hyper-competitive global economy.

Here’s the list of the companies that have managed to stay at the top over the past six decades.

Now let’s shift from companies to people.

The most famous ranking of personal wealth is put together by Forbes.

Is this a closed club, with the same people dominating the list year after year?

Well, there’s considerable turnover in the short run, as noted by Professor Don Boudreaux.

…21 of the still-living 100 richest Americans of only five years ago are no longer in that group today. That’s a greater than 20 percent turnover in a mere half-decade.

There’s a lot of turnover – more than 50 percent – in the medium run, as revealed by Mark Sperry.

Of the 400 people in the 2001 Forbes list of the wealthiest Americans, 230 were not in the 1989 list.

And there’s almost wholesale turnover in the long run, as discovered by Will McBride of the Tax Foundation.

Of the original Forbes 400 from the first edition in 1982, only 35 remain on the list. …Of those on the 1987 Forbes 400 list, only 73 remain there in 2013.

In other words, it’s not easy to stay at the top. New entrepreneurs and investors constantly take the place of those who don’t manage to grow their wealth.

So far, we’ve focused on the biggest companies and the richest people.

But what about ordinary people? Is there also churning for the rest of us?

The answer is yes.

Here are some remarkable findings from a New York Times column by Professor Mark Rank of Washington University.

I looked at 44 years of longitudinal data regarding individuals from ages 25 to 60 to see what percentage of the American population would experience these different levels of affluence during their lives. The results were striking. It turns out that 12 percent of the population will find themselves in the top 1 percent of the income distribution for at least one year. What’s more, 39 percent of Americans will spend a year in the top 5 percent of the income distribution, 56 percent will find themselves in the top 10 percent, and a whopping 73 percent will spend a year in the top 20 percent of the income distribution. …This is just as true at the bottom of the income distribution scale, where 54 percent of Americans will experience poverty or near poverty at least once between the ages of 25 and 60…this information casts serious doubt on the notion of a rigid class structure in the United States based upon income.

A thoroughly footnoted study from the National Center for Policy Analysis has more evidence.

…83 percent of adults born into the lowest income bracket exceed their parents’ income as adults. About 40 percent of people in the lowest fifth of income earners in 1986 moved to a higher income bracket by 1996, and roughly half of the people in the lowest income quintile in 1996 moved to a higher income bracket by 2005. …In both the 1970s and 1980s, 8 percent of children born in the bottom fifth of the income distribution rose to the top fifth. About 20 percent of children born in the middle fifth of the income distribution later rose to the top fifth.

And here’s some of Ronald Bailey’s analysis, which I cited last year.

Those worried about rising income inequality also often make the mistake of assuming that each income quintile contains the same households. They don’t. …In 2009, two economists from the Office of Tax Analysis in the U.S. Treasury compared income mobility in two periods, 1987 to 1996 and 1996 to 2005. The results, published in the National Tax Journal, revealed that “over half of taxpayers moved to a different income quintile and that roughly half of taxpayers who began in the bottom income quintile moved up to a higher income group by the end of each period.” …The Treasury researchers updated their analysis of income mobility trends in a May 2013 study for the American Economic Review, finding that about 75 percent of taxpayers between 35 and 40 years of age in the second, middle and fourth income quintiles in 1987 had moved to a different quintile by 2007.

Last but not least, let’s look at some of Scott Winship’s recent work.

…for today’s forty-somethings who grew up in the middle fifth around 1970…19 percent ended up in the top fifth, 23 percent in the middle fifth, and 14 percent in the bottom fifth… Among those raised in the bottom fifth, 43 percent remain there as adults. …30 percent made it to the top three-fifths… Mobility among today’s adults raised in the top fifth displays the mirror image: 40 percent remain at the top, 37 percent fall to the bottom three-fifths.

The bottom line is that there is considerable income mobility in the United States.

To be sure, different people can look at these numbers and decide that there needs to be even more churning.

My view, for what it’s worth, is that the correct distribution of income is whatever naturally results from voluntary exchange in an unfettered market economy.

I’m far more concerned with another economic variable. Indeed, it’s so important that we’ll close by adding to the three points above.

4. For those who genuinely care about the living standards of the less fortunate, the only factor that really matters in the long run is economic growth.

This is why, like Sisyphus pushing the rock up a hill, I keep trying to convince my leftist friends that growth is the best way to help the poor. I routinely share new evidence and provide real-world data in hopes that they will realize that good results are more important than good intentions.