When the International Monetary Fund endorsed a giant energy tax on the American economy, I was not happy.

And not just because the tax hike would have been more than $5,000 for an average family of four. I also was agitated by the hypocrisy.

…these bureaucrats get extremely generous tax-free salaries, yet they apparently don’t see any hypocrisy in recommending huge tax increases for the peasantry.

And when the similarly un-taxed bureaucrats at the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development added their support for a big tax hike on energy,  I was irked for that reason, and also because they wanted to use much of the money to make government bigger.

I was irked for that reason, and also because they wanted to use much of the money to make government bigger.

…the OECD is basically saying is that an energy tax will be very painful for the poor. But rather than conclude that the tax is therefore undesirable, they instead are urging that the new tax be accompanied by new spending.

Moreover, I also criticized Barack Obama’s former top economist for endorsing a big energy tax.

So does this mean I’m against energy taxation? The answer is yes, but with a big caveat. I want the government to collect tax (hopefully a small amount because we have a small government) in the way that does the least amount of damage to the American economy.

So while my instinct is to oppose any proposed tax, I’m theoretically open to the notion that we can make the tax system less destructive by replacing very bad taxes with taxes that aren’t as bad.

And that’s what some pro-market economists want to do with an energy tax. Here’s some of what Greg Mankiw wrote for the New York Times.

Policy wonks like me have long argued that the best way to curb carbon emissions is to put a price on carbon. The cap-and-trade system President Obama advocates is one way to do that. A more direct and less bureaucratic way is to tax carbon. When polled, economists overwhelmingly support the idea. …It encourages people to buy more fuel-efficient cars, form car pools with their neighbors, use more public transportation, live closer to work and turn down their thermostats. A regulatory system that tried to achieve all this would be heavy-handed and less effective.

In other words, Mankiw argues that not only could the revenue be used to finance equal-sized tax cuts, but the carbon tax would end any need for destructive regulations.

Which creates a win-win scenario, he argues, citing British Columbia as an example.

Bob Inglis, the former Republican congressman from South Carolina, heads the Energy and Enterprise Initiative at George Mason University. A recent winner of the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award, which is given to public officials, he has been pushing for climate change solutions that are consistent with free enterprise and limited government. Environmentalists in the United States would do well to look north at the successes achieved in a Canadian province. In 2008, British Columbia introduced a revenue-neutral carbon tax similar to that being proposed for Washington. The results of the policy have been what advocates promised. The use of fossil fuels in British Columbia has fallen compared with the rest of Canada. But economic growth has not suffered.

Professor Mankiw makes some reasonable points, but now let’s get the other side.

Three of my colleagues at the Cato Institute have just produced a working paper on carbon taxation. They directly address the claims of pro-market advocates of energy taxation.

Within conservative and libertarian circles, a small but vocal group of academics, analysts, and political officials are claiming that a revenue‐neutral carbon tax swap could even deliver a “double dividend”—meaning that the conventional economy would be spurred in addition to any climate benefits. The present study details several serious problems with these claims.

Much of the debate revolves around scientific issues such as the potential long-run harm of carbon emissions.

In the policy debate over carbon taxes, a key concept is the “social cost of carbon,” which is defined as the (present value of) future damages caused by emitting an additional ton of carbon dioxide. …the computer simulations used to generate SCC estimates are largely arbitrary, with plausible adjustments in parameters—such as the discount rate—causing the estimate to shift by at least an order of magnitude. Indeed, MIT economist Robert Pindyck considers the whole process so fraught with unwarranted precision that he has called such computer simulations “close to useless” for guiding policy.

Models about climate change also play a big role.

Additionally, we show some rather stark evidence that the family of models used by the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) are experiencing a profound failure that greatly reduces their forecast utility.

As well as the use of cost-benefit analysis.

…the U.N.’s own report shows that aggressive emission cutbacks—even if achieved through an “efficient” carbon tax—would probably cause more harm than good.

I’m not overly competent to discuss the issues listed above.

But the debate also revolves around what happens with the revenue generated by a carbon tax. For instance, is it used to lower other taxes? Or does it get diverted to fund bigger government?

The Cato authors argue that carbon taxes can be just as damaging – and maybe even more damaging – than existing taxes on labor and capital. And they also fear that revenues from a carbon tax would be used to increase the burden of government spending.

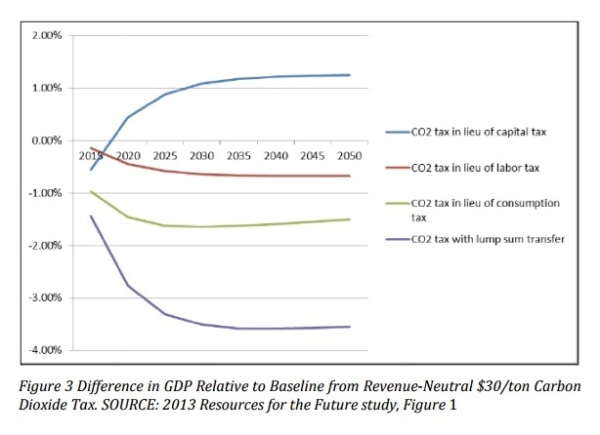

…carbon taxes cause more economic damage than generic taxes on labor or capital, so that in general even a revenue‐ neutral carbon tax swap will probably reduce conventional GDP growth. (The driver of this result is that carbon taxes fall on narrower segments of the economy, and thus to raise a given amount of revenue require a higher tax rate.) Furthermore, in the real world at least some of the new carbon tax receipts would probably be devoted to higher spending (on “green investments”) and lump‐sum transfers to poorer citizens to help offset the impact of higher energy prices. Thus in practice the economic drag of a new carbon tax could be far worse than the idealized revenue‐ neutral simulations depict.

I have mixed feelings about the above passages.

On a per-dollar-raised basis, my gut instinct is that a carbon tax does less damage than revenue sources such as the corporate income tax. So you theoretically would get more growth with a revenue-neutral swap.

But my colleagues are probably right that a carbon tax is more damaging than other taxes, such as the payroll tax (which, after all, is a comparatively less-destructive flat tax on labor income).

Indeed, this is what we see in some of the evidence they cite in their study. You only get better economic performance if carbon tax revenue is used to lower the tax burden on capital.

In any event, the most persuasive argument against the carbon tax is that a big chunk of the new revenue would probably be used to make government even bigger. And this is why I argued back in June that supporters of limited government should reject the siren song of carbon taxation.

Last but not least, I should point out that the evidence from British Columbia is not very persuasive according to the authors of the Cato study.

…in British Columbia—touted as the world’s finest example of a carbon tax—the experience has been underwhelming. After an initial (but temporary) drop, the B.C. carbon tax has not yielded significant reductions in gasoline purchases, and it has arguably reduced the B.C. economy’s performance relative to the rest of Canada.

Now we’re back in an area where I’m unable to provide helpful commentary. Other than a one-time analysis of fiscal policy in Alberta, I’ve never delved into the economic performance and competitiveness of Canadian provinces, so I’ll resist the temptation to make any sweeping statements.

Returning to the big issue, my bottom line is that a carbon tax might be a worthwhile endeavor if Professor Mankiw somehow became economic czar and was allowed to impose policies that never could be altered.

In that scenario, I have confidence that we would get a pro-growth revenue-neutral swap. Which means the negative impact of a carbon tax would be more than offset by the pro-growth effect of eliminating or permanently reducing other taxes.

Unfortunately, we don’t have this scenario in the real world. Instead, I fear that well-meaning proponents of a carbon tax are unwittingly delivering a new source of revenue to a political class in Washington that wants to finance bigger government.