Because of the budgetary implications, I think it’s more important to deal with Medicaid and Medicare than it is to address Social Security.

If left on autopilot, Social Security will eventually consume an additional 2 percent of the private economy.

That’s not good news, but Medicaid (which now includes a big chunk of Obamacare) and Medicare are much bigger threats.

Hopefully, though, we don’t need to engage in fiscal triage and we can reform all the big entitlement programs.

So let’s look at why Social Security needs to be modernized.

First and foremost, the programs is about $40 trillion in the red. And that’s after adjusting for inflation!

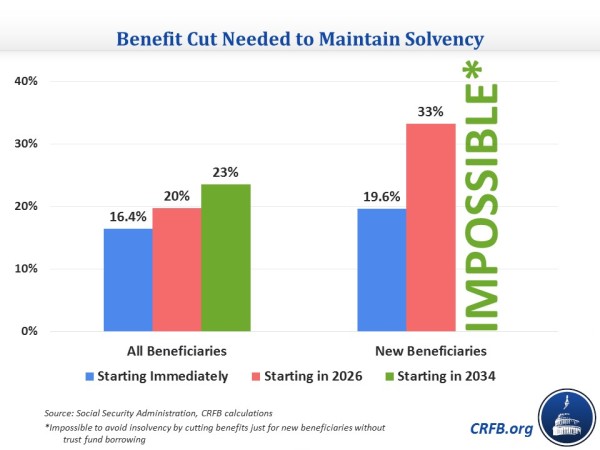

Moreover, the longer we wait, the more difficult reform will be. I don’t always agree with the policy prescriptions of the Committee for a Responsible Budget, but they are very sober-minded in their analysis. And this chart from one of their recent publications shows that waiting until 2026 or 2034 will require more radical changes.

So it should be obvious we need reform, but now the question is what kind of reform.

Some people think the key goal is making the program solvent, but that’s the wrong focus. Sort of like making balance the goal of budgetary policy.

Instead, the goal should be creating a freer society and smaller footprint for government. And that’s why I think personal retirement accounts are the right goal.

And to understand the implications, consider these excerpts from a column in today’s Wall Street Journal. Professor Jeremy Siegel of the University of Pennsylvania explains how the Social Security system has made his retirement less comfortable.

Last month I turned 70 and, thanks to my earnings, became entitled to Social Security’s maximum benefit, currently $3,500 a month, or $42,000 a year. And so, if I live to 90, I will receive $840,000 worth of (inflation-adjusted) benefits. Over the past 50 years, according to the Social Security Administration, the combined taxes paid into the system by me and my employers equaled $329,640. This sounds like a good deal… But the benefits are only about one-third the $2.27 million I would have accumulated had the taxes instead been invested, over time, in a stock index fund. …the benefits I would collect are even less than the $1.28 million I would have accumulated if my “contributions,” as Social Security taxes are euphemistically called, had been placed in U.S. Treasury bonds. …are affluent seniors making out like bandits? Not at all. The bandit is the federal government, which provides benefits that are millions of dollars short of what anyone whose earnings are at or above the tax cap easily could have accumulated on his own.

In effect, Professor Siegel has been forced to pay for a steak and he’s getting a hamburger. Which is a good description of how all entitlement programs operate.

And it’s not just high-income people who get a bad deal. Social Security isparticularly bad for young people. And many minorities also are disadvantagedbecause of their shorter life lifespans.

Moreover, everyone will pay more for their steak and get even less hamburger if politicians deal with the program’s giant shortfall by imposing the wrong type of reform.

But it’s not just that Social Security is bad for individuals. It’s also a burden on the overall economy.

Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute looks at how private savings is impacted by government-run retirement schemes

…fixing Social Security by raising taxes – or, going further, expanding Social Security as many progressives favor – won’t increase retirement income so much as shift it from households to government. …A new report from Canada’s Fraser Institute looks at how Canadian households’ personal saving habits responded to increases in the tax rates used to finance the Canada Pension Plan (CPP). …The Fraser study, authored by Charles Lammam, François Vaillancourt, Ian Herzog and Pouya Ebrahimi, found that for each dollar of additional CPP contributions, Canadian households reduced their personal saving by around 90 cents. As a result, total saving – and thus total future retirement income – would increase by a lot less than you’d think. Households would receive more income from the CPP but less from their own saving.

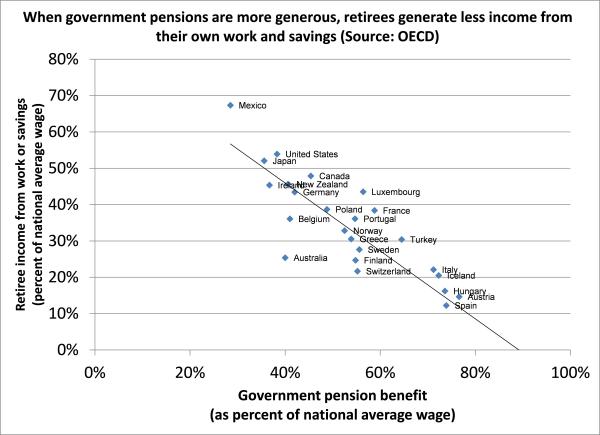

These results are similar to what’s been found in other nations.

I found a similar result across OECD countries: when a country’s government provided an additional dollar of retirement benefits, retirees provided for themselves about 93 cents less in income from savings and work in retirement. …a 2003 analysis by Suzanne Rohwedder and Orazio Attanasio which found that, for the United Kingdom’s earnings-related pension system, individuals reduced personal saving by 65 to 75 cents for each dollar of benefits they expected to receive from the government.

Here’s a very powerful chart on the relationship between private savings and government retirements benefits from another one of Andrew’s articles.

Wow, that’s a powerful relationship. And Biggs isn’t the only expert to produce these results.

All of which underscores why I think we should have a system similar to what they have in Australia or Chile (or even the Faroe Islands).

Here’s my video making the case for personal retirement accounts.

P.S. Two economists at the Federal Reserve produced a study examining why Social Security was first created. It might seem obvious that it was a case of politicians trying to buy votes by creating dependency, but they actually go through the calculations in order to explain how it made sense (from the perspective of people alive at the time) to create a program that now undermines the well-being of the nation.

A well-established result in the literature is that Social Security tends to reduce steady state welfare in a standard life cycle model. However, less is known about the historical effects of the program on agents who were alive when the program was adopted. …we estimate that the original program benefited households alive at the time of the program’s adoption with a likelihood of over 80 percent, and increased these agents’ welfare by the equivalent of 5.9% of their expected future lifetime consumption. …Overall, the opposite welfare effects experienced by agents in the steady state versus agents who experienced the program’s adoption might offer one explanation for why a program that potentially reduces welfare in the steady state was originally adopted.

Gee, what a shocker. Ponzi schemes benefit people who get in at the beginning of the scam.