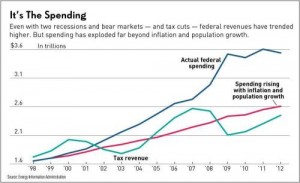

Back in 2012, I shared some superb analysis from Investor’s Business Dailyshowing that the United States never would have suffered $1 trillion-plus deficits during Obama’s first term if lawmakers had simply exercised a modest bit of spending restraint beginning back in 1998.

And the IBD research didn’t assume anything onerous. Indeed, the author specifically showed what would have happened if spending grew by an average of 3.3 percent, equal to the combined growth of inflation plus population.

And the IBD research didn’t assume anything onerous. Indeed, the author specifically showed what would have happened if spending grew by an average of 3.3 percent, equal to the combined growth of inflation plus population.

Remarkably, we would now have a budget surplus of about $300 billion if that level of spending restraint continued to the current fiscal year.

This is a great argument for some sort of spending cap, such as the Swiss Debt Brake or Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights.

But let’s look beyond the headlines to understand precisely why a spending cap is so valuable.

If you look at the IBD chart, you’ll notice that revenues are not very stable. This is because they are very dependent on the economy’s performance. During years of good growth, revenues tend to rise very rapidly. But when there’s a downturn, such as we had at the beginning and end of last decade, revenues tend to fall.

But you don’t have to believe me or IBD. Just look at federal tax revenues over the past 30 years. There have been seven years during which nominal tax revenues have increased by more than 10 percent. But there also have been five years during which nominal tax revenue declined.

This instability means that it doesn’t make much sense to focus on a balanced budget rule. All that means is that politicians can splurge during the growth years. But when there’s a downturn, they’re in a position where they have to cut spending or (as we see far too often) raise taxes.

But if there’s a spending cap, then there is a constraint on the behavior of politicians. And assuming the spending cap is set at a proper level, it means that – over time – there will be shrinking levels of red ink because the burden of government spending will grow by less than the average growth rate of the private economy.

will be shrinking levels of red ink because the burden of government spending will grow by less than the average growth rate of the private economy.

In other words, compliance withmy Golden Rule!

Let’s look at other examples.

Why did Greece get in fiscal trouble? The long answer has to do with ever-growing government and ever-increasing dependency. But the short answer, at least in part, is that a growing economy last decade generated plenty of tax revenue, but rather than cut taxes and/or pay down debt, Greek politicianswent on a spending binge, which then proved to be unsustainable when there was an economic slowdown.*

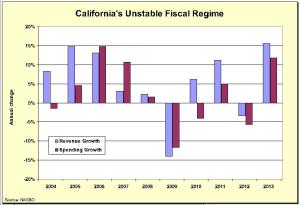

This is also why California periodically gets in fiscal trouble. During years when the economy is growing and generating tax revenue, the politicians can’t resist the temptation to spend the money, oftentimes creating long-run spending obligations based on the assumption of perpetually rapid revenue growth.  These spending commitments then prove to be unaffordable when there’s a downturn and revenues stop growing.

These spending commitments then prove to be unaffordable when there’s a downturn and revenues stop growing.

And as you can see from the accompanying graph, this creates a very unstable fiscal situation for the Golden State. Revenue spikes lead to spending spikes. During a downturn, by contrast, revenues are flat or declining, and this puts politicians in a position of either enacting serious spending restraint or (as you might predict with California) imposing anti-growth tax hikes.

And, in the long run, the burden of spending rises faster than the private sector.

We have another example to add to our list, thanks to some superb research from Canada’s Fraser Institute.

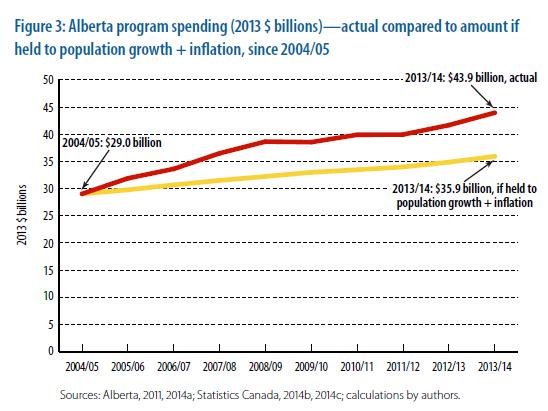

They recently released a study examining fiscal policy in the energy-rich province of Alberta. In particular, the authors (Mark Milke and Milagros Palacios) look at the rapid growth of spending between the fiscal years 2004/05 and 2013/14.

By the mid-2000s, even though the province was again spending at a level that contributed to deficits in the early 1990s, after 2004/05 the province allowed program spending to escalate even further and beyond inflation and population growth. The result was that by 2013/14, the province spent $10,967 per person on government programs. That was $2,002 higher per person than in 2004/05.

Why did the burden of spending climb so quickly? The simple answer is that bigger government was enabled by tax revenue generated by a prospering energy industry.

Over a nine-year period, politicians spent money based on an assumption that high energy prices were permanent and that tax revenues would always be surging.

But now that energy prices have fallen, politicians are suddenly facing a fiscal shortfall. Simply stated, there’s no longer enough revenue for their spending promises.

This fiscal mess easily could have been avoided if the fecklessness of Alberta politicians had been constrained by some sort of spending cap.

The experts at the Fraser Institute explain how such a limit would have precluded today’s dismal situation.

Had the province increased program spending after 2004/05 but within population growth plus inflation, by 2013/14 the province would have spent $35.9 billion on programs. Instead, the province spent $43.9 billion, an $8 billion difference in that year alone. That $8 billion difference is significant. In recent interviews, Alberta Premier Jim Prentice has warned that the drop in oil prices has drained $7 billion from expected provincial government revenues. Thus, past decisions to ramp up program spending mean that additional provincial spending (beyond inflation and population growth) is at least as responsible for current budget gap as the decline in revenues.

And here’s a chart from the study showing how much money would have been saved with modest fiscal restraint.

Unfortunately, that’s not what happened. So now today’s politicians have to deal with a mess that is a consequence of profligate politicians during prior years.**

…the decision by the province to spend (on programs) above the combined effect of population growth and inflation between 2005/06 and 2013/14 inclusive built in higher annual spending obligations, that, once revenues declined, would open up a fiscal gap in the province’s budget. As of 2013/14, the result of spending more on programs than inflation plus population growth combined would warrant meant program expenses were $8 billion higher in that year alone. The province’s past fiscal choices have now severely constricted present choices on everything from balanced budgets to tax relief to additional capital spending. If the province wishes to have a better menu of choices in the future, it must, obviously, control expenditures more carefully.

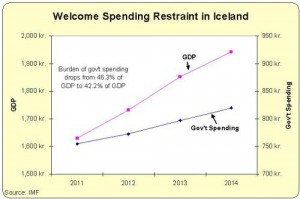

Since I’ve shared all sorts of bad examples of how nations get in trouble by letting spending grow too fast over time, let’s look at a real-world example of a spending cap in action.

As you can see from the chart, Switzerland has enjoyed great success ever since voters imposed the debt brake.

As you can see from the chart, Switzerland has enjoyed great success ever since voters imposed the debt brake.

Indeed, while many other European nations are in fiscal crisis because of big increases in the burden of government spending, the Swiss have experienced economic tranquility in part because the size of the public sector has gradually declined.

The key lesson isn’t that spending restraint is good, though that obviously is important. The most important takeaway is that spending restraint appears to be sustainable only if there is some sort of permanent external constraint on politicians. Like the debt brake. Or like Article 107 of Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

Remember, there are many nations that have enjoyed good results because of multi-year periods of spending restraint. But many of those countries saw their gains evaporate because policies then moved in the wrong direction.

*Greek politicians also took advantage of low interest rates last decade (a result of joining the euro currency) to engage in plenty of debt-financed government spending, which meant the economy was even more vulnerable to a crisis when revenues stopped growing.

**Some of today’s politicians in Alberta are probably long-term incumbents who helped create the mess by over-spending between 2004/05 and today, so I wouldn’t be surprised if they opted for destructive tax hikes instead of long-overdue spending restraint.