There’s an old saying that states are the laboratories of democracy. But since I’m a policy wonk, I focus more on the lessons we can learn from the states about public policy.

- Such as the importance of limiting the destructive nature of taxes.

- Such as the economic benefits of not having an income tax.

- Such as the horrible consequences of adopting an income tax.

- Such as the negative effects of excessive compensation of bureaucrats.

- Such as better job creation in states with less government.

But it’s always good to have more data and evidence.

So I was very interested to see that the Mercatus Center at George Mason University has a new report that ranks states based on their fiscal solvency.

Here are some of the details.

Budgetary balance is only one aspect of a state’s fiscal health, indicating that revenues are sufficient to cover a desired level of spending. But a balanced budget by itself does not mean the state is in a strong fiscal position. State spending may be large relative to the economy and thus be a drain on resources. …How can states establish healthier fiscal foundations? And how can states guard against economic shocks or identify long-term fiscal risks? Before taking policy or budgetary action, it is important to identify where states may have fiscal weaknesses. One approach to help states evaluate their ongoing fiscal performance is to use basic financial indicators that measure short- and long-run fiscal position.

Here are some of the findings.

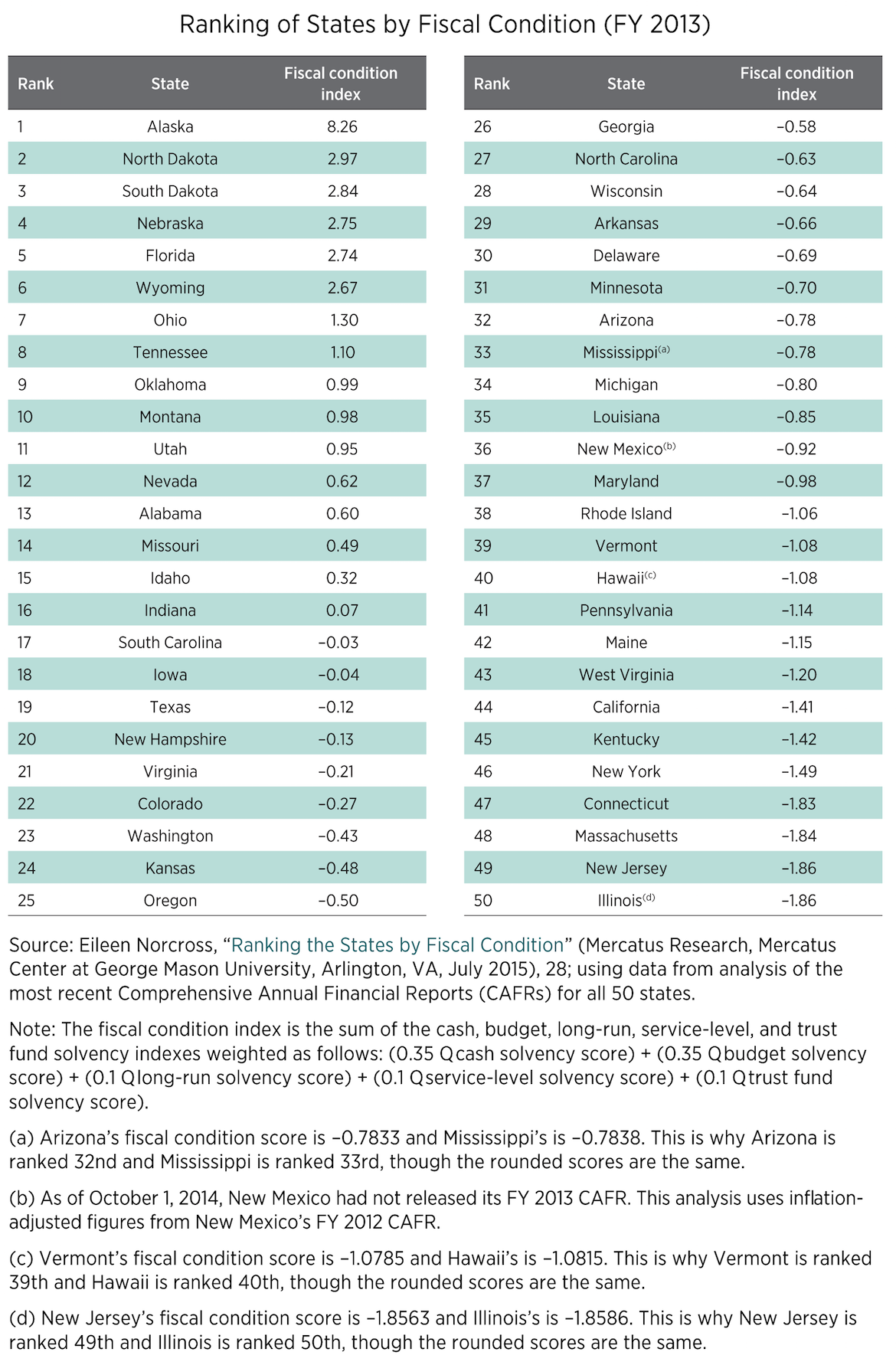

The five dimensions (or indexes) of solvency in this study—cash, budget, long-run, service-level, and trust fund—are…combined into one overall ranking of state fiscal condition. …States with large long-term debts, large unfunded pension liabilities, and structural budgetary imbalances continue to hover near the bottom of the rankings. These states are Illinois, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York. Just as they did last year, states that depend on natural resources for revenues and that have low levels of debt and spending place at the top of the rankings. The top five states are Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Florida.

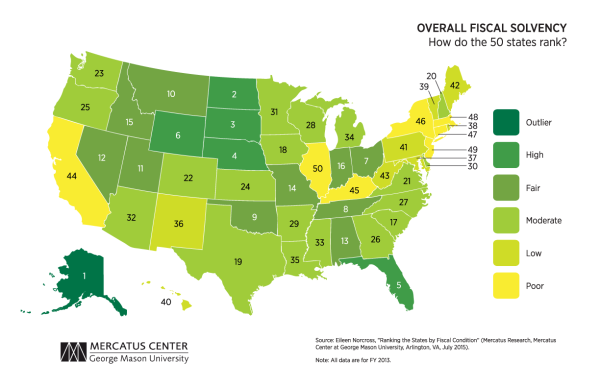

And here’s a map so you can see the rankings of each state. Dark green is good and yellow is bad.

I’m shocked and amazed to see California, Illinois, and New York near the bottom of the list.

Here’s the same information, but in a table so you can see the specific scores for each state.

So what should we learn from these rankings?

According to an editorial from Investor’s Business Daily, there are some very obvious lessons.

What do the most fiscally sound states have in common? Good weather? Oil? Blind luck? Or is it conservative policies such as keeping taxes low, regulations reasonable and spending under control? …There’s only one factor these fiscal winners and losers share in common. And that’s their political leanings. …if you look at the 25 best-performing states, only three could be considered reliably liberal. …There’s only one factor these fiscal winners and losers share in common. And that’s their political leanings. Of the top 10 states in the Mercatus ranking, just two — Florida and Ohio — voted for the Democratic presidential candidate in the past four elections, and just one — Montana — has a Democratic governor. Even if you look at the 25 best-performing states, only three could be considered reliably liberal.

Now let’s shift from policy lessons to political implications. There are several governors and former governors running for President.

Based on the Mercatus ranking, can we draw any conclusions about whether these candidates are in favor of taxpayers? Or do they support big government instead?

We’ll start with the current governors.

- Kasich – Ohio ranks surprisingly high on the list, particularly given the Ohio governor’s expansion of Obamacare in the state. Maybe the state’s #7 ranking is due to fiscal restraint by his predecessors.

- Christie – New Jersey ranks low on the list, and this isn’t a surprise. The relevant question is whether Christie can argue, based on some of the fights he’s had, that the state legislature is an insurmountable impediment to pro-growth reforms.

- Jindal – The governor of Louisiana has proposed some big reforms, but the state’s #35 ranking doesn’t give him any bragging rights on fiscal policy (though the state is leading the way on education reform).

- Walker – Thanks to his high-profile fight with unionized bureaucrats, Walker has a very strong reputation. But his state doesn’t rank very high, and he can’t blame the legislature because it’s GOP-controlled as well. But perhaps the low ranking is a legacy of the state’s historically left-wing orientation.

What about former governors?

Well, there’s probably not much we can say because we don’t have long-run data. There was a similar Mercatus study last year, but that obviously doesn’t help with the analysis of governors that left office years ago.

Nonetheless, here are a few observations.

- Bush – I’m very suspicious of politicians who express an openness to tax hikes, and Bush is in that group. But he did govern Florida for a couple of terms and never flirted with imposing an income tax. And former governors, particularly from recent history, presumably can take some credit for Florida’s relatively high ranking.

- Pataki – Since New York is one of the worst states, Pataki has guilt by implication. But he did lower a few taxes during his tenure, and you also have the same issue that exists with Christie, which is whether a governor should be blamed when the state legislature is hostile to good policy.

- Perry – It’s hard to argue with the success Texas has enjoyed in recent years, and Perry (like Bush) never even hinted at the imposition of a state income tax. Though the #19 ranking shows that there are issues that should have been addressed during Perry’s several terms in office.

- Huckabee – There aren’t many conclusions to draw about Arkansas and Huckabee. He’s been out of office for a while and the state is in the middle of the pack.

The bottom line is that the Mercatus study is very helpful in identifying well-governed (and not-so-well-governed) states, but the newness of the project means we can’t make any sweeping statements about governors because of limited data.

Fortunately, the Cato Institute for years has been publishing a Report Card that grades governors based on fiscal policy. So fans (or opponents) of different candidates can peruse past issues to see the degree to which governors pushed policy in the right or wrong direction.