It’s time for a lesson in tax economics.

Though hopefully today’s topic won’t be as dry and boring as my missives on more technical issues like depreciation and worldwide taxation.

That’s because we’re going to talk about the taxation of workers, which is something closer to home for most of us.

And our lesson comes from Belgium, where the government wants a “new social contract” based on lower “direct” taxes on workers in exchange for higher “indirect” taxes on consumers.

Here are some excerpts from a Bloomberg column by Jean-Michel Paul.

Belgium’s one-year-old government announced measures, radical by that country’s standards, to move the burden of taxation to consumption from labor. The measures are being hailed as the start of a new social contract in the heart of Europe.

But before discussing this new contract, let’s look at how Belgium’s system evolved. Monsieur Paul explains that his nation has a bloated welfare state, which has resulted in heavy taxes on workers (vigorous tax competition precludes onerous taxes on capital).

…In order to sustain large government expenses of more than 50 percent GDP on top of servicing its debt, Belgium became the OECD’s second most-taxed economy. …Belgium made a choice: It decided to heavily tax labor, which it figured, wrongly, was stuck. At the same time, it decided to provide attractive tax treatment to highly mobile capital. The gambit meant that Belgium attracted a large number of wealthy families from higher tax countries, particularly France and the Netherlands, eager to take advantage of the low rates of tax on capital. However, Belgian workers got hammered. In 2014 Belgian workers were the most taxed labor in the developed world, taking home only 46 percent of employers’ labor costs.

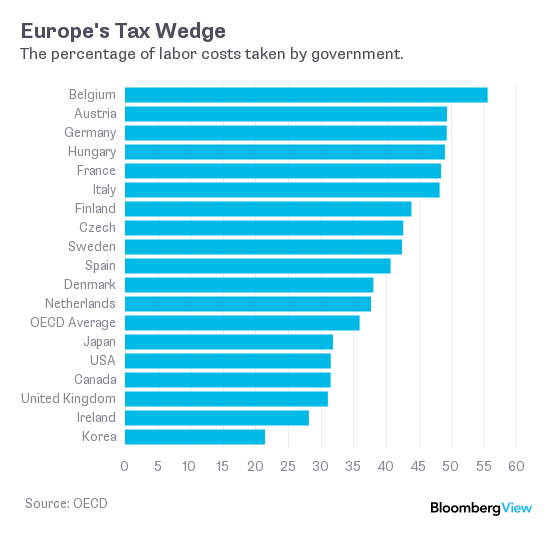

Here’s a chart from the article, showing that Belgian workers are the most mistreated in the developed world.

Keep in mind, by the way, that average rates only measure the overall burden of taxation.

Marginal tax rates, which are what matters most for incentives, are even higher.

According to Wikipedia, the personal income tax has a top rate of 50 percent, and that punitive rate hits a lot of ordinary workers (it’s imposed on income “in excess of €37750”). But there’s also a 13 percent payroll tax on workers and a concomitant payroll tax of more than 30 percent on employers (which, needless to say, is borne by workers).

So an ambitious Belgian worker who wants to earn more money will be confronted by the ugly reality that the government will get the lion’s share of any additional income. Geesh, no wonder Belgium gets a high score (which is not a good outcome) in the World Bank’s “tax effort report card.”

Not surprisingly, high tax rates on labor have led to some predictably bad consequences.

The entrepreneurial class is voting with its feet and regular workers are being taxed into the unemployment line.

This unusual policy mix has increasingly created problems. …Educated professionals and entrepreneurs, those most in demand in other countries, have voted with their feet in borderless Europe. As a result, productivity growth has been limited and Belgium’s economy remained low-growth. Its business start-up rate is the second lowest of the EU. …Whole segments of the country’s industrial tissue, such as the automobile sector, have gradually closed down… This has led to what the European Commission described as “a chronic underutilisation of labour” (read: unemployment) especially among the least qualified and the young. Youth unemployment stands at over 22 percent. …In its 2015 country report the Commission noted that this “reflects Belgium’s high social security charges on labour, which add to the large tax wedge”

Given these horrid numbers, it’s understandable that some policy makers in Belgium want to make changes.

But as Americans have learned (very painfully), “change” doesn’t necessarily mean better policy.

So let’s see what Belgian policy makers have in mind.

The new policy…is to reduce taxes on labor and increase indirect taxes to compensate. Social Security taxes on companies are being reduced to 25 percent from 33 percent over the next two years, bringing an increase in the net after-tax income of 100 euros ($113) per month for low and middle-wage earners. This is mainly financed by an increase in value added tax on electricity consumption. …Belgium is the first to implement what some call a “social VAT” (a tax on consumption to finance social security). …it rewards work and may well change the entitlement mind-set that has hampered innovation and job growth for decades. …a significant step in the right direction, correcting some of the worst distortions of Belgium’s social model.

In other words, politicians in Belgium want to rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Workers will be allowed to earn more of their income when they earn it, but the government will grab more of their income when they spend it.

Now for the economics lesson.

People work because they want to earn money. And they want to earn money so they can spend it. In other words, as Adam Smith observed way back in 1776, “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production.”

Now ask yourself whether the change in Belgian tax policy will boost employment when there’s no change in the tax wedge between pre-tax income (the income you generate) and post-tax consumption (the income you get to spend)?

The answer presumably is no.

This doesn’t mean that the proposed reform is completely useless. It appears that the VAT increase is achieved by ending a preferential tax rate on electricity consumption. And since I don’t like distorting tax preferences, I’m guessing the net effect of the overall package is slightly positive.

In other words, the lower payroll tax rate is unambiguously good and the increase in the VAT burden is only partially bad (I would be more critical if the proposal included an increase in the VAT rate rather than the elimination of a preference).

That being said, now let’s address Belgium’s real problem. Simply stated, it’s impossible to have a good tax system when government spending consumes more than 50 percent of economic output.

In no uncertain terms, an excessive burden of government spending is the problem that needs to be solved.