Remember the big debt limit fight of 2013? The political establishment at the time went overboard with hysterical rhetoric about potential instability in financial markets.

They warned that a failure to increase the federal government’s borrowing authority would mean default to bondholders even though the Treasury Department was collecting about 10 times as much revenue as would be needed to pay interest on the debt.

And these warnings had an effect. Congress eventually acquiesced.

I thought it was a worthwhile fight, but not everyone agrees.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO), for instance, recently released a report about that experience and they suggest that there was a negative impact on markets.

During the 2013 debt limit impasse, investors reported taking the unprecedented action of systematically avoiding certain Treasury securities—those that matured around the dates when the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) projected it would exhaust the extraordinary measures that it uses to manage federal debt when it is at the limit. …Investors told GAO that they are now prepared to take similar steps to systematically avoid certain Treasury securities during future debt limit impasses. …industry groups emphasized that even a temporary delay in payment could undermine confidence in the full faith and credit of the United States and therefore cause significant damage to markets for Treasury securities and other assets.

The GAO even produced estimates showing that the debt limit fight resulted in a slight increase in borrowing costs.

GAO’s analysis indicates that the additional borrowing costs that Treasury incurred rose rapidly in the final weeks and days leading up to the October 2013 deadline when Treasury projected it would exhaust its extraordinary measures. GAO estimated the total increased borrowing costs incurred through September 30, 2014, on securities issued by Treasury during the 2013 debt limit impasse. These estimates ranged from roughly $38 million to more than $70 million, depending on the specifications used.

I confess that these results don’t make sense since it is inconceivable to me that Treasury wouldn’t fully compensate bondholders if there was any sort of temporary default.

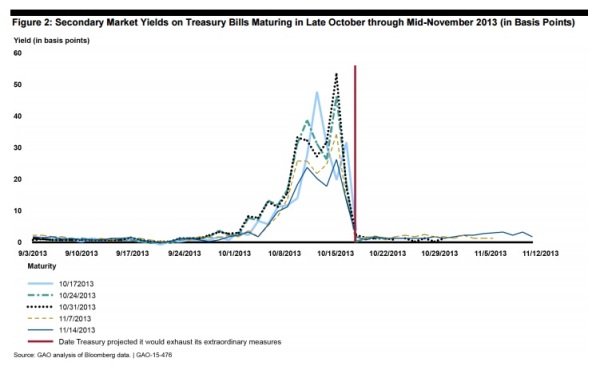

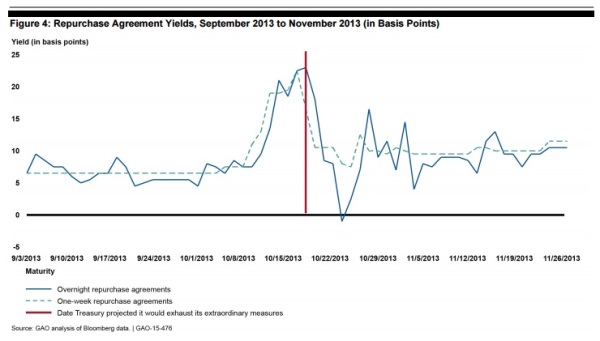

But GAO included some persuasive evidence that investors didn’t have total trust in the government. Here are a couple of charts looking at interest rates.

Both of them show an uptick in rates as we got closer to the date when the Treasury Department said it would run out of options.

Given this data, the GAO argues that it would be best to eviscerate the debt limit.

The bureaucrats propose three options, all of which would have the effect of enabling automatic or near-automatic increases in the federal government’s borrowing authority.

GAO identified three potential approaches to delegating borrowing authority. …Option 1: Link Action on the Debt Limit to the Budget Resolution …legislation raising the debt limit to the level envisioned in the Congressional Budget Resolution would be…deemed to have passed… Option 2: Provide the Administration with the Authority to Increase the Debt Limit, Subject to a Congressional Motion of Disapproval… Option 3: Delegating Broad Authority to the Administration to Borrow…such sums as necessary to fund implementation of the laws duly enacted by Congress and the President.

So is GAO right? Should we give Washington a credit card with no limits?

I don’t think so, but I’m obviously not very persuasive because I actually had a chance to share my views with GAO as they prepared the report.

Here are the details about GAO’s process for getting feedback from outside sources.

…we hosted a private Web forum where selected experts participated in an interactive discussion on the various policy proposals and commented on the technical feasibility and merits of each option. We selected experts to invite to the forum based on their experience with budget and debt issues in various capacities (government officials, former congressional staff, and policy researchers), as well as on their knowledge of the debt limit, as demonstrated through published articles and congressional testimony since 2011. …we received comments from 17 of the experts invited to the forum. We determined that the 17 participants represented the full range of political perspectives. We analyzed the results of the forum to identify key factors that policymakers should consider when evaluating different policy options.

Given the ground rules of this exercise, it wouldn’t be appropriate for me to share details of that interactive discussion.

But I will share some of my 2013 public testimony to the Joint Economic Committee.

Here’s some of what I told lawmakers.

I explained that Greece is now suffering through a very deep recession, with record unemployment and harsh economic conditions. I asked the Committee a rhetorical question: Wouldn’t it have been preferable if there was some sort of mechanism, say, 15 years ago that would have enabled some lawmakers to throw sand in the gears so that the government couldn’t issue any more debt? Yes, there would have been some budgetary turmoil at the time, but it would have been trivial compared to the misery the Greek people currently are enduring. I closed by drawing an analogy to the situation in Washington. We know we’re on an unsustainable path. Do we want to wait until we hit a crisis before we address the over-spending crisis? Or do we want to take prudent and modest steps today – such as genuine entitlement reform and spending caps – to ensure prosperity and long-run growth.

In other words, my argument is simply that it’s good to have debt limit fights because they create a periodic opportunity to force reforms that might avert far greater budgetary turmoil in the future.

Indeed, one of the few recent victories for fiscal responsibility was the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA), which only was implemented because of a fight that year over the debt limit. At the time, the establishment was screaming and yelling about risky brinksmanship.

But the net result is that the BCA ultimately resulted in the sequester, whichwas a huge victory that contributed to much better fiscal numbers between 2009-2014.

By the way, I’m not the only one to make this argument. The case for short-term fighting today to avoid fiscal crisis in the future was advanced in greater detail by a Wall Street expert back in 2011.