When giving speeches outside the beltway, I sometimes urge people to be patient with Washington. Yes, we need fundamental tax reform and genuine entitlement reform, but there’s no way Congress can make those changes with Obama in the White House.

But there are some areas whether progress is possible, and people should be angry with politicians if they deliberately choose to make bad decisions.

For instance, the corrupt Export-Import Bank has expired and there’s nothing that Obama can do to restore this odious example of corporate welfare. It will only climb from the grave if Republicans on Capitol Hill decide that campaign cash from big corporations is more important than free markets.

Another example of a guaranteed victory – assuming Republicans don’t fumble the ball at the goal line – is that there’s no longer enough gas-tax revenue coming into the Highway Trust Fund to finance big, bloated, and pork-filled transportation spending bills. So if the GOP-controlled Congress simply does nothing, the federal government’s improper and excessive involvement in this sector will shrink.

Unfortunately, Republicans have no desire to achieve victory on this issue. It’s not that there’s a risk of them fumbling the ball on the goal line. By looking for ways to generate more revenue for the Trust Fund, they’re moving the ball in the other direction and trying to help the other team score a touchdown!

The good news is that Republicans backed away from awful proposals to increase the federal gas tax.

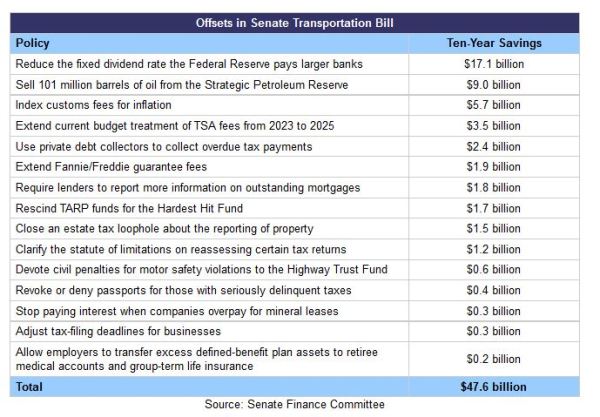

But the bad news is that they’re coming up with other ideas to transfer more of our income to Washington. Here’s a look at some of the revenue-generating schemes in the Senate transportation bill.

Since the House and Senate haven’t agreed on how to proceed, it’s unclear which – if any – of these proposals will be implemented.

But one thing that is clear is that the greed for more federal transportation spending is tempting Republicans into giving more power to the IRS.

Republicans and Democrats alike are looking to the IRS as they try to pass a highway bill by the end of the month. Approving stricter tax compliance measure is one of the few areas of agreement between the House and the Senate when it comes to paying for an extension of transportation funding. …the Senate and House are considering policy changes for the IRS ahead of the July 31 transportation deadline. …With little exception, the Senate bill uses the same provisions that were in a five-month, $8 billion extension the House passed earlier this month. The House highway bill, which would fund programs through mid-December, gets about 60 percent of its funding from tax compliance measures. …it’s…something of a shift for Republicans to trust the IRS enough to back the new tax compliance measures. House Republicans opposed similar proposals during a 2014 debate over highway funding, both because they didn’t want to give the IRS extra authority and because they wanted to hold the line on using new revenues to pay for additional spending.

Gee, isn’t it swell that Republicans have “grown in office” since last year.

But this isn’t just an issue of GOPers deciding that the DC cesspool is actually a hot tub. Part of the problem is the way Congress operates.

Simply stated, the congressional committee system generally encourages bad decisions. If you want to understand why there’s no push to scale back the role of the federal government in transportation, just look at the role of the committees in the House and Senate that are involved with the issue.

Both the authorizing committees (the ones that set the policy) and the appropriating committees (the ones that spend the money) are among the biggest advocates of generating more revenue in order to enable continued federal government involvement in transportation.

Why? For the simple reason that allocating transportation dollars is how the members of these committees raise campaign cash and buy votes. As such, it’s safe to assume that politicians don’t get on those committees with the goal of scaling back federal subsidies for the transportation sector.

And this isn’t unique to the committees that deal with transportation.

It’s also a safe bet that politicians that gravitate to the agriculture committees have a strong interest in maintaining the unseemly system of handouts and subsidies that line the pockets of Big Ag. The same is true for politicians that seek out committee slots dealing with NASA. Or foreign aid. Or military bases.

The bottom line is that even politicians who generally have sound views are most likely to make bad decisions on issues that are related to their committee assignments.

So what’s the solution?

Well, it’s unlikely that we’ll see a shift to random and/or rotating committee assignments, so the only real hope is to have some sort of overall cap on spending so that the various committees have to fight with each other over a (hopefully) shrinking pool of funds.

That’s why the Gramm-Rudman law in the 1980s was a step in the right direction. And it’s why the spending caps in today’s Budget Control Act also are a good idea.

Most important, it’s why we should have a limit on all spending, such as what’s imposed by the so-called Debt Brake in Switzerland.

Heck, even the crowd at the IMF has felt compelled to admit spending caps are the only effective fiscal tool.

Maybe, just maybe, a firm and enforceable spending cap will lead politicians in Washington to finally get the federal government out of areas such astransportation (and housing, agriculture, education, etc) where it doesn’t belong.

One can always hope.

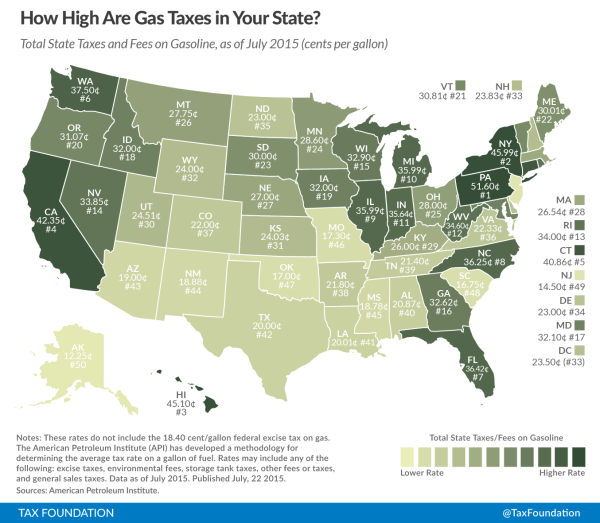

In the meantime, since we’re on the topic of transportation decentralization, here’s a map from the Tax Foundation showing how gas taxes vary by states.

This data is useful (for instance, it shows why drivers in New York and Pennsylvania should fill up their tanks in New Jersey), but doesn’t necessarily tell us which states have the best transportation policy.

Are the gas taxes used for roads, or is some of the money siphoned off for boondoggle mass transit projects? Do the states have Project Labor Agreements and other policies that line the pockets of unions and cause needlessly high costs? Is there innovation and flexibility for greater private sector involvement in construction, maintenance, and operation?

But this is what’s good about federalism and why decentralization is so important. The states should be the laboratories of democracy. And when they have genuine responsibility for an issue, it then becomes easier to see which ones are doing a good job.

So yet another reason to shut down the Department of Transportation.