The conventional wisdom, pushed by the IMF and others, is that Greece’s economy will never recover unless there is substantial debt relief.

Translated into English, that means the Greek government should be allowed to break the contracts it made with the people and institutions that lent money to Greece. That may mean a “haircut,” which would mean lenders (often called creditors) only get back some of what they’ve been promised, or a “default,” which would mean they get none of the money they were promised.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Greece has a full or partial default. And that actually might not be a bad result if it meant an end to bailouts and Greece was immediately forced to balance its budget.

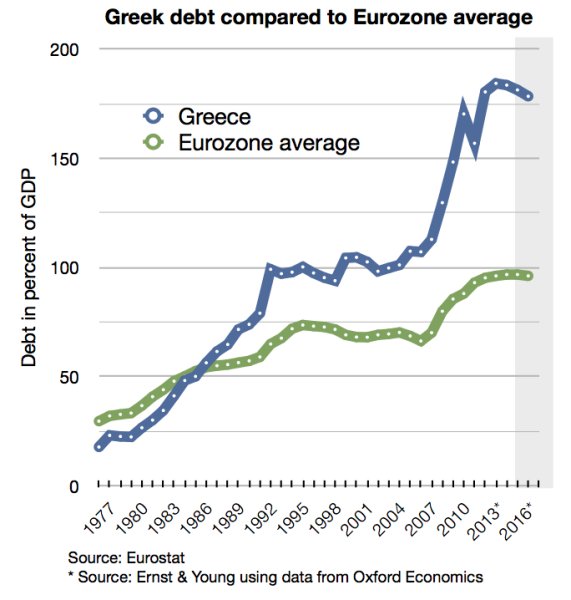

But let’s set that issue aside and look at the specific issue of whether Greece’s debt is unsustainable. Here’s a look at Greek government debt, measured as a share of economic output.

As you can see, when the crisis started in Greece, government debt was about 100 percent of GDP.

Was Greece doomed at that point?

Well, if the situation was hopeless, then someone needs to explain why the United States didn’t collapse after World War II.

As you can see from this chart, debt climbed to more than 100 percent of economic output because of the heavy expense of defeating Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Yet the American economy rebounded after the war (notwithstanding dire predictions from Keynesians) and the debt burden shrank.

So maybe the more interesting issue is to look at how America reduced its debt burden after 1945, which may give us some insights into what should happen (or should have happened) in Greece.

Here’s one question to consider: Did the burden of the federal debt drop between the end of World War II and the 1970s because of big budget surpluses?

Nope. If you look at Table 7.1 of OMB’s Historical Tables, you’ll see that there was a steady increase in the amount of government debt in America after 1945. Yes, there were a few years with budget surpluses, but those surpluses were more than offset by years with budget deficits.

The reason that the national debt shrank as a share of economic output was completely the result of the economy growing faster than the debt.

Here’s an analogy. Imagine you graduate from college and you have $20,000 of credit card debt. That might be a very big burden relative to your income.

But in your 50s and (hopefully) earning a lot more money, you might have $40,000 of credit card debt, yet be in a much stronger financial position.

So the real issue for Greece (and Spain, and Japan, and the United States, etc) is not so much whether the amount of debt shrinks. It’s whether debt is constrained compared to private-sector growth.

That doesn’t require any sort of miracle. Yes, it would be nice if Greece and other nations decided to become like Hong Kong and Singapore, high-growth economies thanks to small government and non-interventionism.

But all that’s needed is a semi-sincere effort to avoid big deficits, combined with a semi-decent amount of economic growth. Which is an apt description of U.S. policy between WWII and the 1970s.

Is it unreasonable to ask Greece to follow that model?

Some may say Greece is now in a different situation because debt levels have climbed too high. Debt in the United States peaked a bit above 100 percent of GDP at the end of World War II, whereas government debt in Greece is now closer to 200 percent of GDP.

It’s certainly true that today’s debt burden in Greece is higher than America’s post-WWII debt burden. So let’s look at another example.

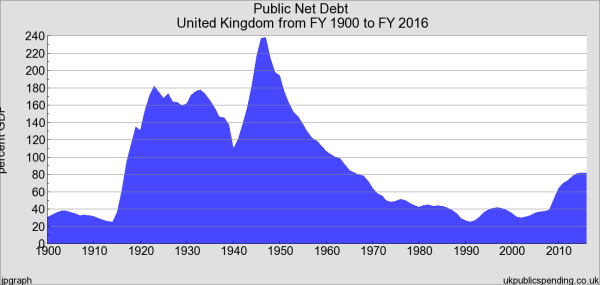

Government debt in the United Kingdom jumped to almost 250 percent of economic output by the end of the World War II.

Did that cause the U.K. economy to collapse? Did Britain have to default?

The answer to both questions is no.

The United Kingdom simply did what America did. It combined a semi-sincere effort to avoid big deficits with a semi-decent amount of economic growth.

And the result, as you can see from the above graph, is that debt fell sharply as a share of GDP.

In other words, Greece can fulfill its promises and pay its bills. And the recipe isn’t that difficult. Simply impose a modest bit of spending restraint and enact a modest amount of pro-growth reforms.

Unfortunately, prior bailouts have given Greece an excuse to avoid reforms. Though the IMF, ECB and European Commission (the so-called troika) have learned somewhat from those mistakes and are now making greater demands of the Greek government as a condition of another bailout.

The problem is the troika doesn’t seem to understand what’s really needed in Greece. They’re pushing for lots of tax increases, which will make it hard for Greece’s private sector to generate growth. The only good news (or, to be more accurate, less bad news) is that the troika doesn’t want as many tax hikes as the Greek government would like.

In other words, don’t be too optimistic about the long-run outcome. Which is basically what I said in this interview on Canadian TV.

The bottom line is that a rescue of the Greek economy is possible. But so long as nobody with any power wants to make the right kind of reforms, don’t hold your breath waiting for good results.