I’m not a big fan of the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

That international bureaucracy is controlled by high-tax nations that want to export bad policy to the rest of the world. As such, the OECD frequently advocates policies that are contrary to sound economic principles.

Here are just a few examples of statist policies that are directly contrary to the interests of the American people.

- The OECD has allied itself with the nutjobs from the so-called Occupy movement to push for bigger government and higher taxes in the United States.

- The bureaucrats are advocating higher business tax burdens, which would aggravate America’s competitive disadvantage.

- The OECD is pushing a “Multilateral Convention” that is designed to become something akin to a World Tax Organization, with the power to persecute nations with free-market tax policy.

- It supports Obama’s class-warfare agenda, publishing documents endorsing “higher marginal tax rates” so that the so-called rich “contribute their fair share.”

- The OECD advocates the value-added tax based on the absurd notion that increasing the burden of government is good for growth and employment.

- It even concocts dishonest poverty numbers to advocate more redistribution in the United States.

- The OECD published a report suggesting numerous schemes to increase national tax burdens.

- Earlier this year, the bureaucrats endorsed a big energy tax on American consumers.

- And, most recently, the OECD embraced quota-driven interventionism on wages for men and women.

With a list like that, you can understand why I’m so upset that American taxpayers subsidize this pernicious bureaucracy. Heck, I’m so opposed to the OECD that I was almost thrown in a Mexican jail for fighting against their anti-tax competition project.

But the point of today’s column isn’t to bash the OECD. The above list is simply to make clear that nobody could accuse the Paris-based bureaucracy of being in favor of small government and free markets.

So if the OECD actually admits that the spending cap in the Swiss Debt Brake is a very effective fiscal rule, that’s a remarkable development. Sort of like criminals admitting that a certain alarm system is effective.

And that’s exactly the message in a report on The State of Public Finances 2015, which was just released by the OECD. Here are some key findings from the preface.

It is understandable that citizens ask why public financial management processes did not guard, in a more effective way, against the vagaries of the economic cycle…the OECD’s recent Recommendation on Budgetary Governance…spells out a number of simple, clear yet ambitious principles for how countries should manage their budgets and fiscal policy processes. …the most salient lesson…is not to seek to avoid altogether the fiscal shocks and cyclical downturns, to which our economies are subject from time to time. The real challenge is to build resilience into our national framework…to mitigate these fiscal shocks. …As to fiscal resilience, this report underpins the wisdom of…fiscal rules.

But what fiscal rules actually work?

This is where the OECD bureaucrats deserve credit for acknowledging an approach with a proven track record, even though the organization often advocates for bigger government. Here are some excerpts from the report’s executive summary.

The European Union’s Stability and Growth Pact…proved largely ineffective in protecting countries from the effects of the fiscal crisis. …Simple and clear fiscal anchors – e.g., the Swiss and German debt brake rules – appear to have been more effective in influencing effective fiscal management.

And here is some additional analysis from the body of the report.

Switzerland’s “debt brake” constitutional rule has proven a model for some OECD countries, notably Germany. …Germany adopted a debt brake rule in 2009… In addition, the United Kingdom recently announced (June 2015) its plan… Furthermore,…it is preferable to combine a budget balance rule with an expenditure rule.

And here are some of the findings from a separate OECD study published earlier this year. Switzerland’s debt brake isn’t explicitly mentioned, but the key feature of the Swiss approach – a spending cap – is warmly embraced.

A combination of a budget balance rule and an expenditure rule seems to suit most countries well. …well-designed expenditure rules appear decisive to ensure the effectiveness of a budget balance rule and can foster long-term growth. …Spending rules entail no trade-off between minimising recession risks and minimising debt uncertainties. They can boost potential growth and hence reduce the recession risk without any adverse effect on debt. Indeed, estimations show that public spending restraint is associated with higher potential growth.

Let me now add my two cents. The research from the OECD on spending caps is good, but incomplete. The main omission is that both the report and the study don’t explain that spending caps primarily are effective because they prevent excessive spending increases when the economy is strong.

As I’ve explained before, citing examples such as Greece, Alberta, Puerto Rico,California, and Alaska, politicians have a compulsive tendency to create new spending commitments during periods when a robust economy is generating lots of tax revenue. But when the economy stumbles and revenues go flat, these spending commitments become unsustainable.

And, all too often, politicians respond with higher taxes.

Speaking of which, the more recent OECD report also has some interesting data on how countries have dealt with fiscal policy in recent years.

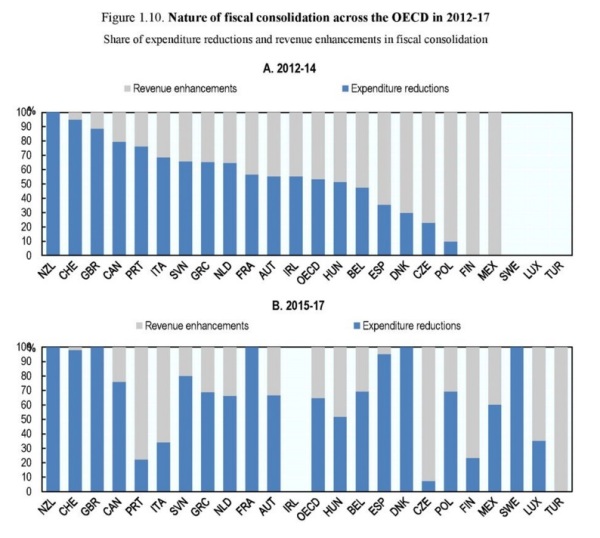

Here are two charts showing fiscal changes from 2012-2014 and projected fiscal changes from 2015-2017.

I’m not sure why the United States isn’t on the list. After all, we actually had some very good changes in 2012-2014 period (though we’ve recently regressed).

But let’s look at some of the other nations (keeping in mind “expenditure reductions” are mostly just reductions in planned increases, just like in the U.S.).

Kudos to New Zealand (NZL), Switzerland (CHE), and the United Kingdom (GBR), all of which took steps to constrain spending over the past three years and all of which intend to be similarly prudent over the next three years.

Cautious applause to France (FRA), Spain (ESP), Denmark (DNK), and Sweden (SWE), all of which at least claim they’ll be prudent in the future.

And jeers to Mexico (MEX) for bad policy in the past and Turkey (TUR) for bad policy in the future, while both the Czech Republic (CZE) and Finland (FIN) deserve scorn for pursuing lots of tax increases in both periods.

Let’s take a moment to elaborate on the nations that have made responsible choices. I’ve already written about fiscal restraint in Switzerland, and I’ve also noted that the United Kingdom has moved in the right direction (even though the current government made some tax mistakes that led me to be very pessimistic when it first took control).

So let’s focus on New Zealand, which is yet another case study showing the value of Mitchell’s Golden Rule.

During the 2012-2014 period, government spending grew by less than 1 percent annually according to IMF data. The government doesn’t intend to be as prudent for the 2015-2017 period, which spending projected to grow by 3 percent annually. But in both cases, nominal spending is growing slower than nominal GDP, and that’s the key to fiscal progress.

Indeed, if you check the OECD data on the overall burden of government spending, the public sector in New Zealand today is consuming 40.5 percent of economic output, which is far too high, but still lower than 44.7 percent of GDP, which was the amount of GDP consumed by government in 2011.

And don’t forget that New Zealand has the world’s freest economy for non-fiscal factors, ranking even above Hong Kong and Singapore.

Let’s conclude by circling back to the issue of spending caps.

It is a noteworthy development that even the OECD has embraced expenditure limits. Especially since the IMF also has endorsed spending caps.

And since spending caps also have widespread support among fiscal experts from think thanks, maybe, just maybe, there’s a chance for real reform.