Back in 2010, I described the “Butterfield Effect,” which is a term used to mock clueless journalists for being blind to the real story.

A former reporter for the New York Times, Fox Butterfield, became a bit of a laughingstock in the 1990s for publishing a series of articles addressing the supposed quandary of how crime rates could be falling during periods when prison populations were expanding. A number of critics sarcastically explained that crimes rates were falling because bad guys were behind bars and invented the term “Butterfield Effect” to describe the failure of leftists to put 2 + 2 together.

Here are some of my favorite examples, all of which presumably are caused by some combination of media bias and economic ignorance.

- A newspaper article that was so blind to the Laffer Curve that it actually included a passage saying, “receipts are falling dramatically short of targets, even though taxes have increased.”

- Another article was entitled, “Few Places to Hide as Taxes Trend Higher Worldwide,” because the reporter apparently was clueless that tax havens were attacked precisely so governments could raise tax burdens.

- In another example of laughable Laffer Curve ignorance, the Washington Post had a story about tax revenues dropping in Detroit “despite some of the highest tax rates in the state.”

- Likewise, another news report had a surprised tone when reporting on the fully predictable news that rich people reported more taxable income when their tax rates were lower.

Now we have a new example for our collection.

Here are some passages from a very strange economics report in the New York Times.

There are some problems that not even $10 trillion can solve. That gargantuan sum of money is what central banks around the world have spent in recent years as they have tried to stimulate their economies and fight financial crises. …But it has not been able to do away with days like Monday, when fear again coursed through global financial markets.

I’m tempted to immediately ask why the reporter assumed any problem might be solved by having governments spend $10 trillion, but let’s instead ask a more specific question. Why is there unease in financial markets?

The story actually provides the answer, but the reporter apparently isn’t aware that debt is part of the problem instead of the solution.

Stifling debt loads, for instance, continue to weigh on governments around the world. …high borrowing…by…governments…is also bogging down the globally significant economies of Brazil, Turkey, Italy and China.

So if borrowing and spending doesn’t solve anything, is an easy-money policy the right approach?

…central banks like the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have printed trillions of dollars and euros… Central banks can make debt less expensive by pushing down interest rates.

The story once again sort of provides the answer about the efficacy of monetary easing and artificially low interest rates.

…they cannot slash debt levels… In fact, lower interest rates can persuade some borrowers to take on more debt. “Rather than just reflecting the current weakness, low rates may in part have contributed to it by fueling costly financial booms and busts,” the Bank for International Settlements, an organization whose members are the world’s central banks, wrote in a recent analysis of the global economy.

This is remarkable. The reporter seems puzzled that deficit spending and easy money don’t help produce growth, even though the story includes information on how such policies retard growth. It must take willful blindness not to make this connection.

Indeed, the story in the New York Times originally was entitled, “Trillions Spent, but Crises like Greece’s Persist.”

Indeed, the story in the New York Times originally was entitled, “Trillions Spent, but Crises like Greece’s Persist.”

Wow, what an example of upside-down analysis. A better title would have been “Crises like Greece’s Persist Because Trillions Spent.”

The reporter/editor/headline writer definitely deserve the Fox Butterfield prize.

Here’s another example from the story that reveals this intellectual inconsistency.

Debt in China has soared since the financial crisis of 2008, in part the result of government stimulus efforts. Yet the Chinese economy is growing much more slowly than it was, say, 10 years ago.

Hmmm…, maybe the Chinese economy is growing slower because of the so-called stimulus schemes.

At some point one might think people would make the connection between economic stagnation and bad policy. But journalists seem remarkably impervious to insight.

The Economist has a story that also starts with the assumption that Keynesian policies are good. It doesn’t explicitly acknowledge the downsides of debt and easy money, but it implicitly shows the shortcomings of that approach because the story focuses on how governments have less “fiscal space” to engage in another 2008-style orgy of Keynesian monetary and fiscal policy

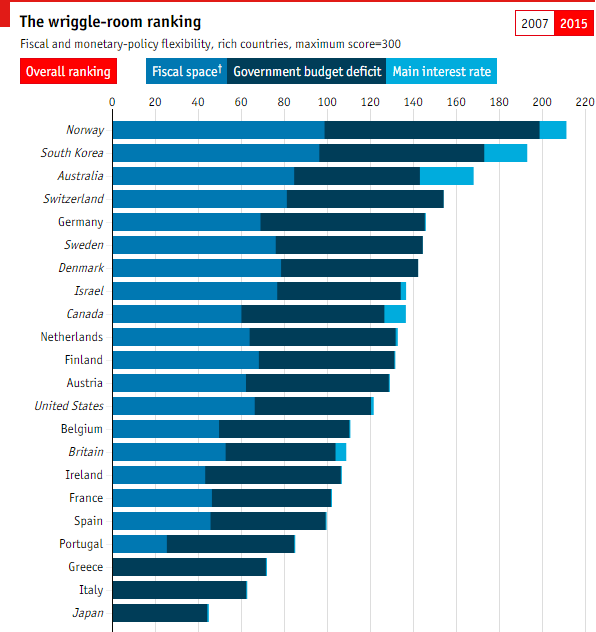

The analysis is misguided, but the accompanying chart is useful since it shows which nations are probably most vulnerable to a fiscal crisis.

If you’re at the top of the chart, because you have oil like Norway, or because you’re semi-sensible like South Korea, Australia, and Switzerland, that’s a good sign. But if you’re a nation like Japan, Italy, Greece, and Portugal, it’s probably just a matter of time before the chickens of excessive spending come home to roost.