Just like the swallows return each year to Capistrano, I eagerly await the Congressional Budget Office’s release of its annual Economic and Budget Outlook.

But not just because I’m a fiscal wonk. I also like perusing this publication to find CBO’s “baseline” forecast for government revenue over the next 10 years.

And once I have that data, it’s then a simple matter to figure out the degree of spending restraint that will reduce red ink and balance the budget.*

Let’s conduct that exercise.

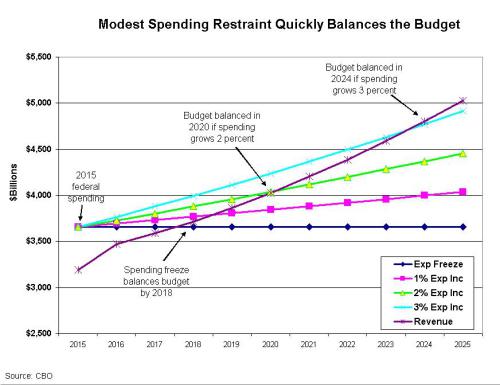

We’ll start by going to page 2 of the report, which reveals that federal tax revenue (assuming there are no changes in law) will grow from $3,189 billion this year to $5,029 billion in 2025. Over that ten-year period, revenues will grow each year by an average of 4.67 percent.

So, at the risk of stating the obvious, this means that red ink will increase if yearly spending increases by more than 4.67 percent, but it also means that the deficit will fall if the burden of federal spending grows by less than 4.67 percent each year.

Indeed, we can easily calculate how easy it is to achieve fiscal balance. Simply take CBO’s estimate of federal spending for the 2015 fiscal year, $3,656, and then look at what happens based on various assumptions for future spending growth.

- A spending freeze means the budget balances in 2018.

- If federal spending increases by 1 percent each year, we balance the budget in 2019.

- If federal spending climbs by 2 percent each year, we balance the budget in 2020.

- And if federal spending jumps by 3 percent each year, we balance the budget in 2024.

Here’s a chart showing these options.

Now let’s explore three implications of this data.

- First, there is no need to cut spending. It would be good to impose genuine spending cuts, to be sure, but progress is possible so long as spending grows slower than revenue. And the real goal should be to make sure that spending grows slower than the private sector.

- Second, there is no need to raise taxes. A lot of beltway types would like voters to believe that our fiscal problems are so huge that tax increases are both necessary and desirable. That’s obviously wrong. Indeed, tax hikes almost surely enable more spending rather than deficit reduction.

- Third, when Washington insiders assert that tax increases are needed to preclude “savage” and “draconian” spending cuts, they’re using the dishonest DC definition of a “cut,” which is when spending doesn’t rise as fast as previously forecast.

At this point, you may be wondering, “Gee, if it’s so simple, why don’t we already have a balanced budget?”

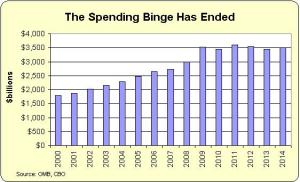

The main problem is that politicians generally don’t like spending restraint. Between 2000 and 2009, for instance, they let spending grow nearly four times faster than revenue.

That being said, we’ve actually made progress over the past five years thanks to a nominal spending freeze.** And as outlined above, we can make more progress in the near future with a few more years of modest spending restraint.

That being said, we’ve actually made progress over the past five years thanks to a nominal spending freeze.** And as outlined above, we can make more progress in the near future with a few more years of modest spending restraint.

The real key is whether we can maintain fiscal discipline. In the long run, there’s very little hope of spending restraint unless there’s genuine entitlement reform.

And getting that type of reform probably won’t be possible if politicians think they can just raise taxes instead. Particularly a value-added tax, which the European evidence shows is a money machine for bigger government.

Probably the best way of getting good policy would be some sort of long-run spending control process, akin to the Swiss Debt Brake. If politicians know they can only increase spending by, say, two percent each year, that will encourage them to finally prioritize the budget and make some long-overdue reforms.

*As I have written, over and over again, restraining the size and scope of the federal government should be the main goal of fiscal policy. Deficits and debtare undesirable, of course, but they’re best viewed as symptoms of the real problem, which is too much spending.

** The good news is that spending grew very slowly beginning in 2010. The bad news is that spending rose so fast last decade (particularly in 2009) that the burden of federal spending is still much larger than it was when Bill Clinton left office.