The modern welfare state is a disaster. But rather than go into lengthy details, let’s simply look at some very powerful images (click for enlarged view).

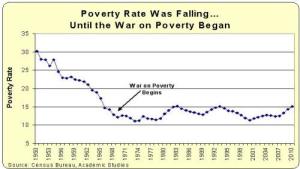

Probably the most damning evidence is that the poverty rate in America was steadily falling after World War II. But then Lyndon Johnson declared a “war on poverty” and got Washington more involved in the business of income redistribution. So what happened? The poverty rate stopped falling.

Probably the most damning evidence is that the poverty rate in America was steadily falling after World War II. But then Lyndon Johnson declared a “war on poverty” and got Washington more involved in the business of income redistribution. So what happened? The poverty rate stopped falling.

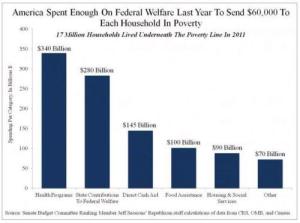

But it’s also sobering to see how much money is being spent on income-redistribution programs. Taxpayers at the federal, state, and local level are coughing up more than $1 trillion every year to subsidize poverty. To give an idea of how much inefficiency and waste permeates the system, this is enough to give every poor household $60,000.

But it’s also sobering to see how much money is being spent on income-redistribution programs. Taxpayers at the federal, state, and local level are coughing up more than $1 trillion every year to subsidize poverty. To give an idea of how much inefficiency and waste permeates the system, this is enough to give every poor household $60,000.

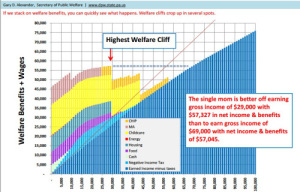

Poor people are among the biggest victims of the welfare state. Redistribution programs create a dependency trap because of very high implicit tax rates on productive behavior. Simply stated, handouts are so generous that poor people who enter the labor force generally will have lower living standards than those who remain wards of the state.

Poor people are among the biggest victims of the welfare state. Redistribution programs create a dependency trap because of very high implicit tax rates on productive behavior. Simply stated, handouts are so generous that poor people who enter the labor force generally will have lower living standards than those who remain wards of the state.

So what’s the solution to this mess?

Fortunately, we have a case study that points us in a productive direction.

The Bill Clinton-era welfare reforms, pushed through by Republicans in Congress, were a big success. Here are some excerpts from an article written by an expert at the Brooking Institution.

Between 1994 and 2004, the caseload declined about 60 percent, a decline that is without precedent. The percentage of U.S. children on welfare is now lower than it has been since at least 1970. …More than 40 studies conducted by states since 1996 show that about 60 percent of the adults leaving welfare are employed at any given moment and that, over a period of several months, about 80 percent hold at least one job. …Again, these sweeping changes are unprecedented. …Equally important, with earnings leading the way, the total income of these low-income families increased by more than 25 percent over the period (in constant dollars). Not surprisingly, between 1994 and 2000, child poverty fell every year and reached levels not seen since 1978. In addition, by 2000, the poverty rate of black children was the lowest it had ever been.

This is an older article from 2006, so there was obviously some movement in the wrong direction after the recent recession.

Nonetheless, the big message from welfare reform in the 1990s is that blank-check welfare entitlements are greatly inferior to a federalism-based approachthat allows states to innovate and experiment to see what works best.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is that the Clinton welfare reforms only addressed a minor part of the welfare state. Moreover, the Obama Administration has undermined some of the modest progress that was achieved in the 1990s.

So we need a new offensive to deal with the broader deficiencies of the current system, which is a disaster for both taxpayers and poor people.

But if we use Clinton’s welfare reforms as a model, there is considerable progress that can be achieved. Diana Furchtgott-Roth of Economics 21 has anew study on precisely this topic.

She identifies some of the major redistribution programs in Washington.

This paper examines the evolution of major U.S. welfare programs since 1998—shortly after the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), the 1996 federal welfare reform signed into law by President Clinton, went into effect.

The paper chronicles the average amount of aid provided, as well as length of time on public assistance, focusing on the following programs: SNAP; Temporary Aid to Needy Families, or TANF (established by PRWORA); Medicaid; and Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV).

And she points out these programs are an expensive failure, but proposes a way to address the problem.

…while the U.S. economy has since improved, participation in such programs has generally not declined. This paper concludes that there is ample scope for states to reform welfare, and it proposes two substantial changes: (1) cap welfare spending at the rate of inflation and the number of Americans in poverty; and (2) allow states to direct savings from welfare programs to other budget functions. …this paper finds that federal savings through 2013 would, after accounting for inflation and the number of Americans in poverty, total $1.3 trillion had welfare funding remained at 1998 levels.

The key is federalism.

States should have the freedom to experiment to see what policies are most effective. Under such conditions, successful states would serve as models for other states—and, possibly, models for further federal welfare reform. Indeed, successful welfare reforms have already been observed in North Carolina, New York, Indiana, and Rhode Island. …Providing states increased flexibility to adjust resource levels between welfare programs offers numerous advantages. For instance, states with low food prices but high housing costs might shift resources from SNAP to housing programs. In addition, states could divert funding from existing programs to new ones, such as community-based programs that prove successful.

Her bottom line is that the status quo is a failure.

Antipoverty programs should be judged by how successfully they help lift people out of poverty. By this measure, the country’s welfare programs performed poorly during the Great Recession and its aftermath: welfare costs and eligibility have, as this paper has documented, largely expanded, with few gains in poverty reduction. …The status quo is plainly unacceptable. New solutions, not more funding, are the answer. …empower states to choose welfare policies that best serve their most vulnerable families, as well as those that best fit their political demands.

An excellent study and a very sound proposal.

Though I would make one very important modification.

It’s clearly a step in the right direction if the federal government turns all income-redistribution programs into a block grant so that states can decide how to allocate the money and address poverty.

But the long-run goal should be to eliminate any role for Washington, even as a provider of block grants.

In an ideal world, the block grant should be immediately capped and then gradually phased out. Let state and local governments decide how to tax and spend in this arena.

P.S. The bureaucrats at the OECD (subsidized by our tax dollars) are pushing a new definition of poverty that is really a stalking horse for more income redistribution.