Politicians and bureaucrats are very creative in their pursuit of bad policy.

In some case, I’m not even sure how to classify their actions.

When the government squandered $224,000-plus for research on condom sizes, for instance, I thought that story easily could be classified as wasteful spending. But then I discovered the research was related to the fact that the government limits the types of condoms that manufacturers can offer, so maybe this was an example of mindless over-regulation.

Now I’m facing another quandary about how to classify a story. I’m not sure to add the following nightmare to my ever-growing list of theft-by-government stories, or whether it belongs in my collection of stupid-drug-war stories.

Here’s some background from a report in Reason by Jacob Sullum. It’s about a robbery at an airport.

When he visited relatives in Cincinnati the winter before last, Charles Clarke, a 24-year-old college student, took with him $11,000 that he had saved from wages, financial aid, and family gifts because he did not want to lose it. He did not count on the armed robbers at the airport, who took every last cent as he was about to board a flight back to Orlando in February 2014.

So did Mr. Clarke call the cops to report the theft?

Well, not exactly.

…the thieves were cops, who justified confiscating Clarke’s life savings by claiming his luggage and cash smelled like pot.

But the cops didn’t arrest Mr. Clarke for possession of marijuana (they didn’t find any). Nor did they charge him with having smoked marijuana (I guess even cops realize that would be a pointless waste of resources).

However, they did take his money on the very tenuous (and completely unproven) proposition that it may have been connected with a drug deal.

Even more amazing, the burden of proof is now on Mr. Clarke to prove his money is innocent, so the presumption of innocence granted by the Constitution doesn’t apply!

More than a year later, Clarke is still trying to get his money back… But the federal prosecutors who are pursuing forfeiture of Clarke’s money do not have to prove he was a drug dealer. …the government keeps the cash based on “probable cause that it was proceeds of drug trafficking or was intended to be used in an illegal drug transaction,” and the burden is on Clarke to recover it.

Why is this happening?

Well, I’ve written many times that incentives matter. That’s true for taxpayers and it’s true for bureaucrats.

And true for cops as well.

…the number of seizures by police at the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport exploded from a couple dozen a year in the late 1990s to nearly 100, totaling $2 million, in 2013. By pursuing forfeiture under federal law through the Justice Department’s Equitable Sharing Program, the airport cops can keep up to 80 percent of the loot while letting the feds do most of the work.

Yup, this is what’s called “policing for profit.”

This is so outrageous that even some folks who like big government are on Mr. Clarke’s side. Here are some excerpts from a report published by Vox.

Under federal and state laws that allow what’s called “civil forfeiture,” law enforcement officers can seize someone’s property without proving the person was guilty of a crime; they just need probable cause to believe the assets are being used as part of criminal activity, typically drug trafficking. Police can then absorb the value of this property — be it cash, cars, guns, or something else — as profit: either through state programs, or under a federal program known as Equitable Sharing that lets local and state police get up to 80 percent of the value of what they seize as money for their departments. So police can not only seize people’s property without proving involvement in a crime, but they have a financial incentive to do so.

Not only is there no presumption of innocence, the government actually puts the money on trial rather than the person.

In typical criminal cases, the government has to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that someone is guilty of a crime. But in civil forfeiture cases, the government only has to show that it’s more likely than not that the property was intended to buy drugs or obtained from selling drugs. The bar is so low in part because it’s the property itself on trial, not the person whose property was taken — and due process rights cover people, not property. So in Clarke’s situation, the case is literally called United States of America v. $11,000.00 in United States Currency. (No, this is not a joke.)

The Vox report also looks at the perverse incentives created by this system.

…under the federal program, 13 different law enforcement agencies from Ohio and Kentucky are seeking a cut of Clarke’s $11,000 — even though 11 of those agencies weren’t involved in the seizure. The competition should show how lucrative these kind of seizures are in the eyes of law enforcement: they’re an opportunity to turn a costly counter-narcotics operation into a profitable venture for the law enforcement agencies involved (or even not, in Clarke’s case).

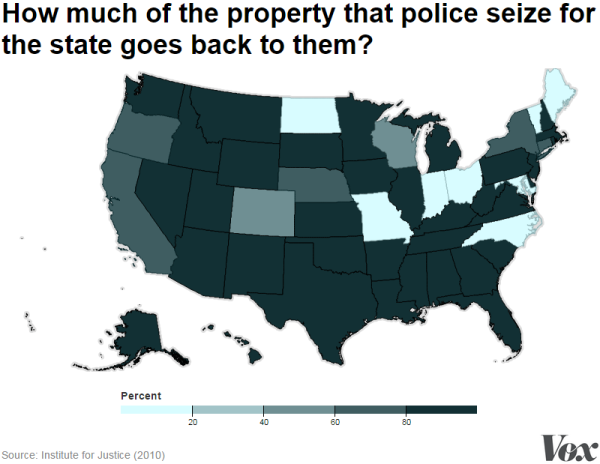

And here’s a look at how different states approach the issue.

The darker the state, the bigger the incentive for law enforcement agencies to steal money.

There’s also good evidence that these venal laws target minorities.

A bulk of forfeiture cases also appear to disproportionately afflict minorities. Clarke, who’s black, said he felt like he was racially profiled. Of the 400 federal court cases reviewed by the Post in which people challenged a seizure and got some money back, most of the victims were black, Hispanic, or another racial minority.

This is a good opportunity to say something about race relations.

I don’t have any tolerance for racial grievance mongers like Jesse Jackson or Al Sharpton, and I don’t automatically assume racism when a black man like Eric Garner dies because of an interaction with cops.

But I do have great sympathy for law-abiding African-Americans who have to deal getting hassled for “driving while black.” Not to mention “riding trains while black.” And as we see from Mr. Clarke’s plight, we also have to include “flying while black.”

By the way, I’m not arguing that profiling is always illegitimate. As Walter Williams has explained, it’s sometimes just common sense.

But if profiling – or even the perception of profiling – causes resentment, then doesn’t it make sense to make sure it isn’t being used promiscuously? Shouldn’t it be reserved for situations where law enforcement is seeking to protect life, liberty, or property? Needless to say, civil asset forfeiture and the drug war are definitely not good reasons to utilize a tool with societal downsides.