More than two years ago, I cited some solid research from the Tax Foundation to debunk some misguided analysis from the New York Times about the taxation of multinational companies.

Well, it’s déjà vu all over again, as the late Yogi Berra might say. That’s because we once again find something in the New York Times that cries out for correction.

Here’s some of what Patricia Cohen recently wrote about ostensibly generating lots of tax revenue by pillaging America’s top-1 percent taxpayers.

…what could a tax-the-rich plan actually achieve? As it turns out, quite a lot…the government could raise large amounts of revenue exclusively from this small group, while still allowing them to take home a majority of their income.

Oh, how generous of her for deciding that the awful, evil rich people can keep perhaps keep 50.1 percent of what they earn. Sounds like she should join the other cranks advising Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom.

But I’m getting distracted. Let’s focus on the more important topic, which is her claim that it’s easy to generate a lot of tax revenue by soaking the rich.

The top 1 percent on average already pay roughly a third of their incomes to the federal government, according to a Treasury Department analysis…how much more revenue could be generated by asking the rich to pay a larger share of their income in taxes?

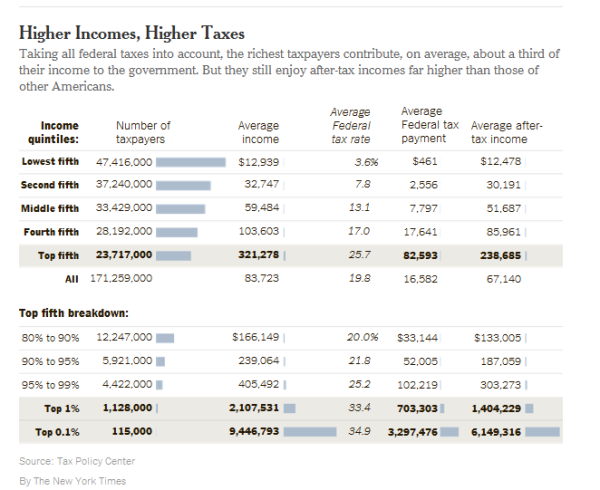

Interestingly, Ms. Cohen shares some data showing that the rich already are paying far higher tax rates than the rest of us. Here’s the table that accompanied her article.

Normal people would look at those numbers, or at similar data produced by the IRS, and conclude that we’re already selectively over-penalizing upper-income taxpayers.

But statists see income in the private sector as belonging to the state, so there’s no such thing as too much money for government.

And Ms. Cohen seems to have this attitude. She engages in some simplistic calculations to estimate how much loot could be seized.

Raising their total tax burden to, say, 40 percent would generate about $157 billion in revenue the first year. Increasing it to 45 percent brings in a whopping $276 billion. …Move a rung down the ladder and expand the contribution of those in the 95th to 99th percentile — who earn on average $405,000. Raising their total tax rate to 30 percent from a quarter of their total yearly income would generate an additional $86 billion. …A 35 percent share produces $176 billion.

Gee, how easy, at least on paper. If the politicians can figure out how to raise average tax rates to 45 percent for the rich (and 35 percent for the upper-middle class), then they get about $450 billion of additional tax revenue every year.

And you can buy a lot of votes with that much of other people’s money.

But sometimes things that are simple on paper are not so simple in reality.

It turns out that raising someone’s average tax rate (total tax payments/total income) requires some very big (and very bad) decisions on marginal tax rates (tax paid on the last dollar of income/last dollar of income).

Scott Greenberg of the Tax Foundation does that heavy lifting and his analysismakes mincemeat out of Ms. Cohen’s argument.

…how exactly would Congress go about raising the effective tax rate of the 1% from 33.4 percent to 45 percent? The article is not specific about this point. In fact, the article acknowledges that it is “sidestepping… the messy question of just which taxes would be increased.” This is irresponsible policy analysis… When one examines exactly which taxes would have to be increased to raise the effective tax rate of the 1% from 33.4 percent to 45 percent, the endeavor begins to appear much more difficult than the New York Times portrays.

For instance.

…the top tax bracket on ordinary income is 39.6%. How high would Congress have to raise this rate, in order to raise the effective tax rate of the 1% to 45 percent? According to our estimates, Congress would have to raise the top rate on ordinary income to 74 percent, in order to raise the effective rate of the 1% from 33.4 percent to 45 percent. …What if Congress decided to increase, not only the top rate on ordinary income, but also the top rate on capital gains and dividends? …According to our estimates, Congress would have to raise the top rate on ordinary income, capital gains, and dividends to 56 percent, in order to increase the effective rate of the 1% to 45 percent.

In other words, if you target the rich with higher income tax rates, you’d have to have a rate higher than the confiscatory structure that existed before any of the Reagan tax cuts.

Or you could boost the top rate “only” to 56 percent, but only by also dramatically increasing the double taxation of dividends and capital gains.

And that might not be very smart, at least if you care about economic performance. Scott explains.

The high rates that would need to be in place to tax the 1% at a 45 percent effective rate would almost certainly have negative economic consequences. According to our Taxes and Growth model, raising the top rate on ordinary income to 74 percent would shrink the size of the U.S. economy by 3.5 percent in the long run, by discouraging labor and pass-through business. While this tax increase would raise $3.49 trillion over 10 years under conventional scoring, after taking its economic effects into account, it would only raise $2.37 trillion. This is a significantly smaller figure than that cited by the New York Times. Furthermore, raising the top rate on ordinary income, capital gains, and dividends to 56 percent would lead to an even larger decline in GDP, of 4.9 percent. This is because taxes on investment income are especially harmful to long-term economic growth. After taking economic effects into account, this proposal would only raise $1.96 trillion over 10 years.

So the politicians would still have some extra revenue, but they would destroy several dollars of private economic activity for every one dollar of revenue they would collect.

In what world would that be a good trade?

Oh, and by the way, those revenue estimates overstate how much money the politicians would collect. In the real world, higher tax rates also would increase tax avoidance and tax evasion.

…none of these figures take into account the effects of increased tax evasion and profit shifting by wealthy Americans that would surely occur in response to such high rates. After all, when taxes rise, taxpayers have more incentives to avoid them. And it is well-documented that, when rates on capital gains rise, shareholders simply defer their realizations, making it difficult to raise much revenue from tax increases on capital gains income.

So here’s the bottom line.

…the New York Times claims that the federal government could raise large amounts of revenue by taxing the rich just a little bit more. In fact, taxes on the rich would have to go up enormously in order to bring in the sorts of revenue figures cited by the article. The negative economic effects of these tax increases would then reduce these revenues considerably.

I’d like to think Scott’s analysis will change minds and cause statists to reassess their desire to impose high tax rates.

But I’m not overly hopeful. Let’s not forget that some of these people aren’t particularly interested in generating more revenue for politicians. Their real motive is hate and envy.