When major changes occur, especially if they’re bad, people generally will try to understand what happened so they can avoid similar bad events in the future.

This is why, when we’re looking at major economic events, it’s critical to realize that narratives matter.

For instance, generation after generation of American students were taught that the Great Depression was the fault of capitalism run amok. But we now have lots of evidence that bad government policy caused the Great Depression and that the downturn was made more severe and longer lasting thanks to further policy mistakes by Hoover and Roosevelt.

The history textbooks are probably still wrong, but at least there’s a chance that interested students (and non-students) will come across more accurate explanations of what happened in the 1930s.

More recently, the same thing happened after the financial crisis. The statists immediately tried to convince people that the 2008 mess was a consequence of “Wall Street greed” and “deregulation.”

Fortunately, many experts were available to point out that the real problem was bad government policy, specifically easy money from the Fed and the corrupt system of subsidies from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

So hopefully future history books won’t be as wrong about the financial crisis as they were about the Great Depression.

I raise these examples because I want to address another historical inaccuracy.

Let’s go back about 100 years ago to the s0-called “progressive era.” The conventional story is that this was a period when politicians reined in some of the excesses of big business. And if it wasn’t for that beneficial government intervention, we’d all still be oppressed peasants working in sweatshops.

There’s just one small problem with this narrative. It’s utter nonsense.

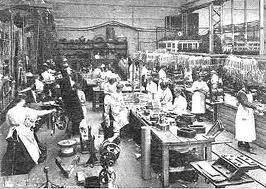

Let’s look specifically at the issue of sweatshops. Writing for the Independent Institute, Ben Powell looks at the history of sweatshops and whether workers were being mistreated.

He starts with a bit of history.

Sweatshops are an important stage in the process of economic development. As Jeffery Sachs puts it, “[S]weatshops are the first rung on the ladder out of extreme poverty”. …Working conditions have been harsh and standards of living low throughout most of human history. …Prior to the Industrial Revolution, textile production was decentralized to the homes of many rural families or artisans, and output was limited to what could be produced on the spinning wheel and hand loom. …Yarn spinning was mechanized in 1767 with the invention of the spinning jenny, and water power was harnessed shortly thereafter. With these inventions and steam power later, large-scale textile factories that are similar to today’s sweatshops emerged. The conditions in these early sweatshops were worse than those in many Third World sweatshops today. In some factories, workers toiled for sixteen hours a day, six days per week.

Then he looks at what actually happened in Great Britain, which is where sweatshops began.

Yet workers flocked to the mills. …sweatshop workers…were attracted by the opportunity to earn higher wages than they could elsewhere. In fact, economist Ludwig von Mises defended the factory system of the Industrial Revolution,…writing, “The factory owners did not have the power to compel anybody to take a factory job. They could only hire people who were ready to work for the wages offered to them. Low as these wage rates were, they were nonetheless more than these paupers could earn in any other field open to them.” …Mises’s argument is supported by historical evidence. Economist Joel Mokyr reports that workers earned a wage premium of 15 to 30 percent by working in the factories compared with other alternatives. The transformation of Great Britain during this time was dramatic. As economist and historian Donald McCloskey describes it, “In the 80 years or so after 1780 the population of Britain nearly tripled, the towns of Liverpool and Manchester became gigantic cities, the average income of the population more than doubled… Peter Lindert and Jeffery Williamson similarly find impressive gains in the standard of living between 1781 and 1851. Farm labor’s standard of living went up more than 60 percent, blue-collar workers’ standard increased more than 86 percent, and overall workers’ standard increased more than 140 percent. Along with this increase in the standard of living came a decrease in the share of women and children working beginning sometime between 1815 and 1820.

Ben then looks at the American experience.  Once again, he finds that sweatshops allowed workers to earn more income than they could by staying on the farm.

Once again, he finds that sweatshops allowed workers to earn more income than they could by staying on the farm.

And this was part of a process that enabled the United States to become much richer over time.

…workers flocked to the mills. At first, in the cities north of Boston it was mainly rural women and girls who left the farm to populate the early textile mills. During the 1830s in Lowell, a woman could earn $12 to $14 a month (in 1830s dollars) and after paying $5 for room and board in a company boarding house would have the rest left over for clothing, leisure, and savings. It wasn’t uncommon for women to return home to the farm after a year with $25 to $50 in a bank account. This was far more money than they could have earned on the farm and often more disposable cash than their fathers had. …much like in Great Britain, living standards improved over time. In 1820, before the Industrial Revolution, annual per capita income in the United States stood at a little more than $2,000. By 1850, it had grown by 50 percent to more than $3,000 and then doubled again by 1900 to more than $6,600. Along with the rise in incomes came improvements in working conditions and greater consumption.

Eventually, of course, the sweatshops disappeared. But Ben explains that it was because of higher living standards rather than government intervention.

Sweatshops are eliminated mainly through the process of industrialization that raises a country’s income. The increased income comes from increased worker productivity, which raises the upper bound of compensation. The increased productivity isn’t just in one firm, but in many firms and industries, and thus workers’ next-best alternatives improve, raising the lower bound of compensation. As the economy grows, the competitive process pushes wages up. Because health, safety, leisure, and so on are normal goods, workers demand more of their compensation on these margins as their total compensation increases. The result is the eventual disappearance of sweatshops.

Now let’s look at the broader issue of whether the “progressive era” was bad news for big business.

The answer is yes and no. Politicians imposed lots of legislation that was bad for the free market, but the crony capitalists of that era were big supporters of intervention.

Tim Carney elaborates in a column for the Washington Examiner.

Every American knows the fable of the Progressive Era and that “trust buster” Teddy Roosevelt wielding the big stick of federal power to battle the greedy corporations. We would be better off if more people knew the work of the man who dismantled this myth: historian Gabriel Kolko… His thesis: “The dominant fact of American political life” in the Progressive Period “was that big business led the struggle for the federal regulation of the economy.”

Here’s what really happened.

Many corporate titans in the early 20th Century, buying into the pervasive hubris of the day, believed that a state-managed economy was the inevitable end of a rational society—the conclusion of what Standard Oil’s top lobbyist Samuel Dodd called the “march of civilization.” Competition, in their eyes, was destructive redundancy. “Competition is industrial war,” James Logan of the U.S. Envelope Company wrote in 1901. “Ignorant, unrestricted competition carried to its logical conclusion means death to some of the combatants and injury for all.” Steel baron Andrew Carnegie constantly strove to turn the steel industry into a cartel and keep prices high. Competition, however, always had a way pulling prices down. As Carnegie wrote in 1908, “It always comes back to me that Government control, and that alone, will properly solve the problem.” Kolko also showed how the socialists welcomed corporate-state collusion to advance monopoly as part of “progress.”

And, as Tim explains, it’s still happening today.

This has its echoes in contemporary progressive politics… When conservatives challenged Obamacare’s individual mandate, the White House had the backing of the insurance industry and the hospital lobby. After Obama won at the Supreme Court, liberal Bill Scher wrote in the New York Times that progressive victories historically flow from the Left’s alliances with Big Business. …Liberal scholar William Galston at the Brookings Institution explains the economics at play. “Corporations have sizeable cash flows and access to credit markets, which gives them a cushion against adversity and added costs,” he wrote in 2013, explaining why the big guys often welcome regulation.

In other words, big business often is the enemy of genuine capitalism and free markets.

Not only did the big companies, including insurance and pharmaceuticals, support Obamacare.

They’re now supporting the corrupt Import-Export Bank.

And they’re perfectly happy to support higher taxes, at least when the rest of us are being victimized.

They also supported the sleazy TARP bailout.

The moral of the story is not just the big business can be just as bad as big labor. The real moral of the story is captured by this poster.