It’s remarkable to read that European politicians are agitating to spend more money, supposedly to make up for “spending cuts” and austerity.

To put it mildly, their Keynesian-based arguments reflect a reality-optional understanding of recent fiscal policy on the other side of the Atlantic.

Here’s some of what Leonid Bershidsky wrote for Bloomberg.

Just as France’s and Italy’s poor economic results prompt the leaders of the euro area’s second and third biggest economies to step up their fight against fiscal austerity, it might be appropriate to ask whether they even know what that is.

An excellent question. As I’ve already explained, austerity is a catch-all phrase that includes bad policy (higher taxes) and good policy (spending restraint).

But with a few notable exceptions, European nations have been choosing the wrong kind of austerity (even though Paul Krugman doesn’t seem to know the difference).

As a result, the real problem of bloated government keeps getting worse.

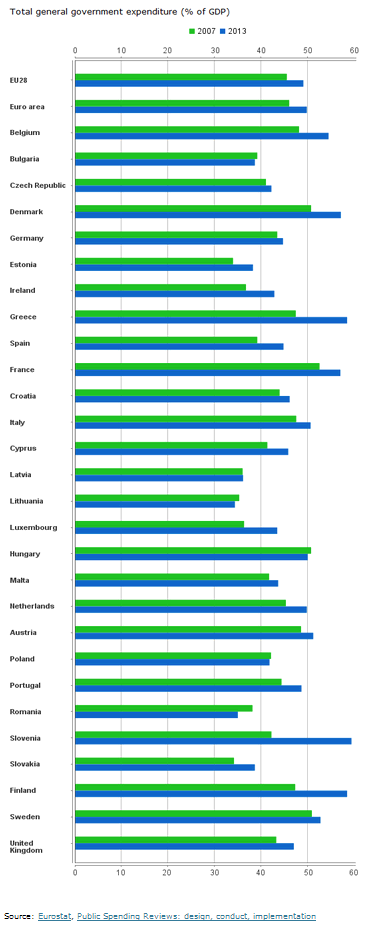

Government spending in the European Union, and in the euro zone in particular, is now significantly higher than before the 2008 financial crisis. …Among the 28 EU members, public spending reached 49 percent of gross domestic product in 2013, 3.5 percentage points more than in 2007.

Here’s a chart showing how the burden of government spending has become more onerous since 2007.

As you can see, all the big nations of Western Europe have moved in the wrong direction.

Only a small handful of countries in Eastern Europe that have trimmed the size of the public sector.

Bershidsky does explain that the numbers today are slightly better than they were at the peak of the economic downturn, though not because of genuine fiscal restraint.

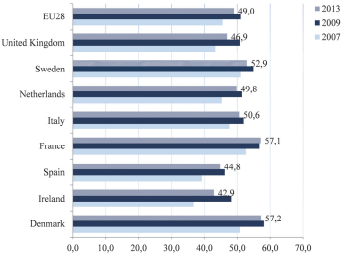

The spending-to-GDP-ratio first ballooned by 2009, exceeding 50 percent for the EU as a whole, and then shrank a little… That, however, was not the result of government’s austerity efforts: Rather, the spending didn’t go down as much as the economies collapsed, and then didn’t grow in line with the modest rebound.

Here are some examples he shared.

I suppose France deserves a special shout out for managing to expand the size of government between 2009 and 2013. That’s what you call real commitment to statism!

The article also cites an example that is both amusing and tragic, at least in the sense that there’s no genuine seriousness about reforming hte public sector.

Even when spending cuts are made…, the whole public spending system’s glaring inadequacy is not affected. …The ushers at the Italian Parliament, whose job is to carry messages in their imposing gold-braided uniforms, made $181,590 a year by the time they retired, but will only make as much as $140,000 after Renzi’s courageous cut. If you wonder what on earth could be wrong with getting rid of them altogether and just using e-mail, you just don’t get European public expenditure.

I particularly embrace Bershidsky’s conclusion.

There is no rational justification for European governments to insist on higher spending levels than in 2007. The post-crisis years have shown that in Italy, and in the EU was a whole, increased reliance on government spending drives up sovereign debt but doesn’t result in commensurate growth. The idea of a fiscal multiplier of more than one — every euro spent by the government coming back as a euro plus change in growth — obviously has not worked. In fact, increased government interference in the economy, in the form of higher borrowing and spending as well as increased regulation, have led to the shrinking of private credit. …Unreformed government spending is a hindrance, not a catalyst for growth.

Amen.

Politicians will never want to hear this message, but government spending undermines economic performance by diverting resources from the the economy’s productive sector.

Here’s my video on the theoretical evidence against government spending.

And here’s the video looking at the empirical evidence against excessive spending.

P.S. Other Europeans who have correctly analyzed Europe’s spending problem include Constantin Gurdgiev and Fredrik Erixon.