Using a comparison of Jamaica and Singapore, I recently argued that growth should trump inequality.

Simply stated, a growing economic pie is much better for poor people that incentive-sapping redistribution programs that trap people in dependency.

In other words, nations with smaller government and less intervention produce better results than nations with bloated governments and lots of meddling.

You see that relationship by comparing Jamaica and Singapore, and you also see it when examining other nations.

This is fresh in my mind since I just spoke at the Kyiv stop on the Free Market Road Show.

I told the audience about the reforms that Ukraine needs to strengthen economic performance, but I probably should have simply read what one expert recently wrote about Ukraine and Poland.

Here’s some of what Allister Heath had to say for London’s City A.M.

In the dreadful communist days, Ukraine and Poland used to be equally poor. The former was part of the Soviet Union, and Poland was one of the USSR’s satellite nations, belonging to the Warsaw pact. In 1990, both countries had roughly the same GDP per capita – their economies were eerily similar. A quarter of a century later, everything has changed… It’s a tale of two economic models, and a central reason why Russia – a waning world power desperate to cling on to its historic zone of influence – has felt able to bully Ukraine in such a shocking way. …The big difference is that Poland has pursued free-market policies, reducing the size of its state, introducing a strict rule of law and respect for property rights, privatising in a sensible way, avoiding the kleptocracy and corruption that has plagued regimes in Kiev, and embracing as much as possible Western capitalism.

Allister cites World Bank data to state that “Poland’s GDP per capita is now 3.3 times greater than Ukraine’s.”

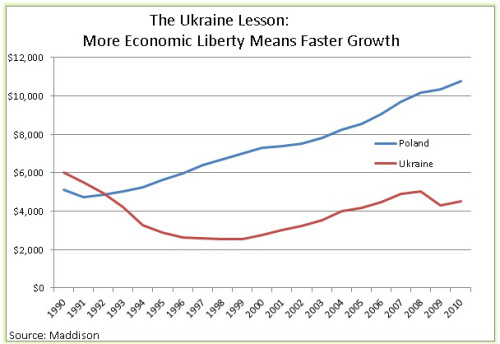

I prefer the Angus Maddison data, which doesn’t show quite the same divergence. But if you look at the chart, you still see an amazing change in relative living standards in the two nations.

These numbers are shocking. Even with the Maddison data, Poland quickly passed Ukraine after the collapse of communism and now enjoys more than twice the level of per-capita output (and would probably have about three times as much per-capita GDP if the numbers were updated through 2014).

This doesn’t mean, by the way, that Poland is a pro-market paradise. As Allister explains, it’s not exactly Hong Kong or Singapore.

Poland’s tax system remains far too oppressive, the red tape is too strict and the bureaucracy still too redolent of the bad old days, the labour market is excessively regulated, parts of the population rejects elements of the new order and the country remains relatively poor, which explains why so many of its most ambitious folk have moved to the UK and elsewhere. But Poland has been one of the great success stories of the post-communist era, whereas Ukraine, tragically, has been one of the great failures.

To add some details, Freedom of the World ranks Poland as the 59th-freest economy in the world.

That’s not great, but it’s a lot better than Ukraine, which ranks only 126 out of 152 nations (behind even Russia!).

More important, Poland’s overall score was only 3.90 in 1990 and now it is up to 7.20.

Ukraine, by contrast, has only climbed to 6.16.

As I’ve already stated, their big problem is Putinomics. If they want to catch the West, they need free markets and small government.