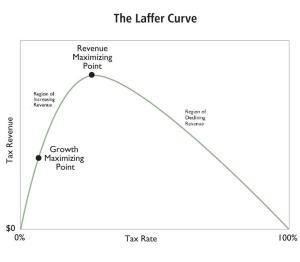

In my writings on the Laffer Curve, I probably sound like a broken record because I keep warning that a nation should never be at the revenue-maximizing point.

That’s because there’s lots of good research showing that there are ever-increasing costs to the economy as tax rates approach that level.

That’s because there’s lots of good research showing that there are ever-increasing costs to the economy as tax rates approach that level.

So the question that policy makers should ask themselves is whether they’re willing to impose $10 or $20 of damage to the private sector in order to collect $1 of additional revenue.

New we have further evidence. Let’s take a look at a new study by economists from Spain, Arizona, and California. Here’s the issue they decided to study.

As top earners account for a disproportionate share of tax revenues and face the highest marginal tax rates, such proposals lead to a natural tradeoff regarding tax revenue. On the one hand, increases in tax revenue are potentially non-trivial given the income generated by high-income households. On the other hand, the implementation of such proposals would increase marginal tax rates precisely where they are at their highest levels, and thus where the individual responses are expected to be larger. Therefore, revenue increases might not materialise.

And here’s what they found.

…the increase in overall tax collections – including tax collections at the local and state level and from corporate income taxes – is much smaller: 1.6%. Figure 2 shows why. As τ increases there is a substantial decline in labour supply, the capital stock, and aggregate output across steady states. Aggregate output, for example, declines by almost 12% when τ = 0.13. Hence, the government collects taxes from a smaller economy… The message from these findings is clear. There is not much available revenue from revenue-maximising shifts in the burden of taxation towards high earners…and that these changes have non-trivial implications for economic aggregates.

The key takeaways from that passage are the findings about “a smaller economy” and the fact that there are “non-trivial implications for economic aggregates.”

That means less prosperity.

And the authors even acknowledge that the damage to the productive sector is presumably larger than what they found in this research.

…it is important to reflect on the absence of features in our model that would make our conclusions even stronger. First, we have abstracted away from human capital decisions that would be negatively affected by increasing progressivity. Since investments in individual skills are not invariant to changes in tax progressivity, larger effects on output and effective labour supply – relative to a case with exogenous skills – are to be expected. Second, we have not modelled individual entrepreneurship decisions and their interplay with the tax system. Finally, we have not modelled a bequest motive, or considered a dynastic framework more broadly. In these circumstances, it is natural to conjecture that the sensitivity of asset accumulation decisions to changes in progressivity would be larger than in a life-cycle economy. Hence, even smaller effects on revenues would follow.

Richard Rahn’s latest column in the Washington Times also looks at this issue, reviewing the work of James Mirrlees, an economist who was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1996.

Back in 1971, a Scottish economist by the name of James A. Mirrlees wrote a groundbreaking paper, in which he attempted to answer the question of what an optimum income-tax regime would look like… Mr. Mirrlees had been an adviser to the British Labor Party, which supported the high tax rates in effect at that time. He did a careful analysis of the variation of people’s skills and the effect tax rates had on their incentives to earn. Much to his surprise, he found the optimum tax rate on high earners was about 20 percent… In his 1971 paper, Mr. Mirrlees concluded, “I must confess that I had expected the rigorous analysis of income taxation in the utilitarian manner to provide an argument for high tax rates. It has not done so.”

In other words, tax rates above 20 percent ultimately are self-defeating – even if you’re a statist and you want to maximize the size of the welfare state.

And there’s plenty of data from around the world on specific case studies that show the negative impact of class-warfare taxation, including research from theUnited States, Denmark, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom.

And here’s Part II of my video series on the Laffer Curve, which provides additional evidence.

P.S. If you want some good data showing why Krugman and other class warriors are wrong about tax rates, Alan Reynolds did a very good job of skewering their analysis.