I’m a big advocate of the Laffer Curve.

Simply stated, it’s absurdly inaccurate to think that taxpayers and the economy are insensitive to changes in tax policy.

Yet bureaucracies such as the Joint Committee on Taxation basically assume that the economy will be unaffected and that tax revenues will jump dramatically if tax rates are boosted by, say, 100 percent.

In the real world, however, big changes in tax policy can and will lead to changes in taxable income. In other words, incentives matter. If the government punishes you more for earning more income, you will figure out ways to reduce the amount of money you report on your tax return.

In the real world, however, big changes in tax policy can and will lead to changes in taxable income. In other words, incentives matter. If the government punishes you more for earning more income, you will figure out ways to reduce the amount of money you report on your tax return.

This sometimes means that people will choose to be less productive. Why bust yourderrière, after all, if government confiscates a big chunk of your additional earnings? Why make the sacrifice to set aside some of your income when the government imposes extra layers of tax onsaving and investment? And why allocate your money on the basis of economic efficiency when you can reduce your taxable income by dumping your investments into something like municipal bonds that escape the extra layers of tax?

Or people can decide to hide some of the money they earn from the grasping claws of the IRS. Contractors can work off the books. Workers can take wages under the table. Business owners can overstate their expenses in order to reduce taxable income.

To reiterate, people respond to incentives. And that means you can’t estimate what will happen to tax revenues simply by looking at changes in tax rates. You also need to look at what’s happening to the amount of income people are willing to both earn and report.

Which is why I’m interested in some new research from two Canadian economists, one from the University of Toronto and one from the University of British Columbia. They looked at how rich people in Canada responded when their tax rates were altered.

Here are some excerpts from the study, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

In this paper we estimate the elasticity of reported income using the sub-national variation across Canadian provinces.

…Comparing across provinces and through time, we find that elasticities are large for incomes at the top of the income distribution… The provincial tax rates for high earners vary strongly across the country, ranging from a low of 10 percent in Alberta to a high of 25.75 in Quebec. …at the top of the income distribution…these taxpayers have access to substantial financial advice that may facilitate tax avoidance. …We pay particular attention to the categories for $250,000 and those that report income between $150,000 and $250,000 as that income range is the closest to the P99 cutoff on which we focus.

Interestingly, the economists state that upper-income taxpayers should be less sensitive to tax rates today because less of their income is from investments.

…the source of incomes among those at the top has shifted substantially over the last half century from capital income toward earned income. All else equal, this change would tend to make income shifting or tax avoidance more difficult now than in earlier times.

Yet their results suggest that the taxable income of highly productive Canadians (those with incomes in the top 1 percent or the top 1/10th of 1 percent) is very sensitive to changes in tax rates.

The third column has the results for the bottom nine tenths of the top one percent, P99 to P99.9. Here, the estimate is a positive and significant 0.364. Finally, the top P99.9 percentile group shows an elasticity of 1.451, which is highly significant and large. …our estimate of 0.689 for P99 is high, and 1.451 for P99.9 very high.

And because rich people can raise or lower their taxable income in response to changing tax rates, this has big Laffer Curve implications.

According to the research, the revenue-maximizing tax rate for the top 1 percent is 44.4 percent and the revenue-maximizing tax rate for the even more successful top 1/10th of 1 percent is 27.5 percent!

The magnitude of our estimates can be put into context by calculating the revenue-maximizing tax rate τ∗, which is the rate corresponding to the peak of the so-called ‘Laffer Curve’. At this point, an incrementally higher rate will raise no further net revenue as the mechanical effect of the tax increase will be completely offset by the behavioural response of lower taxable income. …Plugging a = 1.81 and e = 0.689 into equation (8) yields an estimate for τ∗ of 44.4 percent. In Figure 1, four provinces have a top marginal tax rate for 2013 under 44.4 percent and six provinces are higher. Using the P99.9 estimate of 1.451, the revenue maximizing tax rate τ∗ would be only 27.5 percent. If true, this would suggest all provinces could increase revenue by lowering the tax rate for those in income group P99.9.

By the way, you read correctly, the revenue-maximizing tax rate for the super rich is lower than the revenue-maximizing tax rate for the regular rich.

This almost certainly is because very rich taxpayers get a greater share of their income from business and investment sources, and thus have more control over the timing, level, and composition of their earnings. Which means they can more easily suppress their income when tax rates go up and increase their income when tax rates fall.

That’s certainly what we see in the U.S. data and I assume Canadians aren’t that different.

But now it’s time for a big caveat.

I don’t want to maximize revenue for the government. Not from the top 1/10th of 1 percent. Not from the top 1 percent. I don’t want to maximize the amount of revenue coming from any taxpayers. If tax rates are near the revenue-maximizing point, it implies a huge loss of private output per additional dollar collected by government.

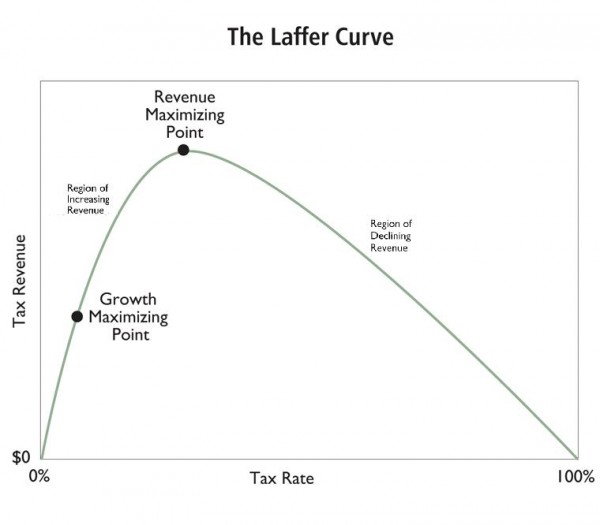

As I’ve repeatedly argued, we want to be atthe growth-maximizing point on the Laffer Curve. And that’s the level of tax necessary to finance the few legitimate functions of government.

As I’ve repeatedly argued, we want to be atthe growth-maximizing point on the Laffer Curve. And that’s the level of tax necessary to finance the few legitimate functions of government.

That being said, the point of this blog post is to show that Obama, Krugman, and the rest of the class-warfare crowd are extremely misguided when they urge confiscatory tax rates on the rich.

Unless, of course, their goal is to punish success rather than to raise revenue.

P.S. Check out the IRS data from the 1980s on what happened to tax revenue from the rich when Reagan dropped the top tax rate from 70 percent to 28 percent.

I’ve used this information in plenty of debates and I’ve never run across a statist who has a good response.

P.P.S. I also think this polling data from certified public accountants is very persuasive.

I don’t know about you, but I suspect CPAs have a much better real-world understanding of the impact of tax policy than the bureaucrats at the Joint Committee on Taxation.