Since I’m an economist, I generally support competition.

But it’s time to admit that competition isn’t always a good idea. Particularly when international bureaucracies compete to see which one can promote the most-destructive pro-tax policies.

For instance, I noted early last year that the bureaucrats at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) were pushing a new scheme to increase the global tax burden on the business community.

Then I wrote later in the year that the International Monetary Fund was even more aggressive about pushing tax hikes, earning it the label of being the Dr. Kevorkian of the world economy.

That must have created some jealousy at the OECD, so those bureaucrats earlier this year had a taxpalooza party and endorsed a plethora of class-warfare tax hikes.

Now the IMF has responded to the challenge and is pushing additional tax increases all over the world.

For example, the bureaucrats want much higher taxes on energy use, both in the United States and all around the world.

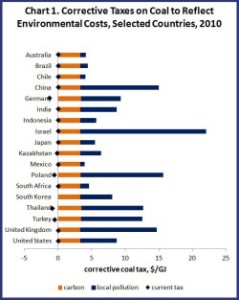

This chart from the IMF shows how much the bureaucracy thinks that the tax should be increased just on coal consumption.

This chart from the IMF shows how much the bureaucracy thinks that the tax should be increased just on coal consumption.

The chart doesn’t make much sense, particularly if you don’t know anything about “gigajoules.” Fortunately, Ronald Bailey of Reason translates the jargon and tells us how this will impact the average American household.

The National Journal reports that the tax rate would be $8 per gigajoule of coal and a bit over $3 per gigajoule of natural gas. Roughly speaking a ton of coal contains somewhere around 25 gigajoules of energy, which implies a tax rate of $200 per ton. …The average American household uses about 11,000 kilowatt hours annually, implying a hike in electric rates of about $1,100 per year due to the new carbon tax. Since the average monthly electric bill is about $107, the IMF’s proposed tax hike on coal would approximately double how much Americans pay for coal-fired electricity. A thousand cubic feet (mcf) of natural gas contains about 1 gigajoule of energy. The average American household burns about 75 mcf of natural gas annually so that implies a total tax burden of $225 per residential customer.

To be fair, the IMF crowd asserts that all these new taxes can be – at least in theory – offset by lower taxes elsewhere.

…we are generally talking about smarter taxes rather than highertaxes. This means re-calibrating tax systems to achieve fiscal objectives more efficiently, most obviously by using the proceeds to lower other burdensome taxes. The revenue from energy taxes could of course also be used to pay down public debt.

Needless to say, I strongly suspect that politicians would use any new revenue to finance a larger burden of government spending. That’s what happened when the income tax was enacted. That’s what happened when the payroll tax was enacted. That’s what happened when the value-added tax was enacted.

If you think something different would happen following the implementation of an energy tax, you win the grand prize for gullibility.

But let’s give the IMF credit. The bureaucrats are equal opportunity tax hikers. They don’t just want higher taxes in the United States. They give the same message everywhere in the world.

Here are some excerpts from an editorial about Spanish fiscal policy in the Wall Street Journal.

Madrid last month cut corporate and personal tax rates, simplified Spain’s personal-income tax system and vowed to close loopholes. That’s good news… So leave it to the austerity scolds at the International Monetary Fund to call for tax increases. …Specifically, the Fund wants Spain to raise value-added taxes, alcohol and tobacco excise taxes, tourism taxes, and various environmental and energy levies: “It will be critical to protect the most vulnerable by increasing the support system for them via the transfer and tax system.”

Gee, I suppose that we should be happy the IMF didn’t endorse higher income taxes as well.

The good news is that the Spanish government may have learned from previous mistakes that tax hikes don’t work.

Rather than heed this bad advice, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and Finance Minister Cristobal Montoro are cutting government spending and eliminating wasteful programs to reduce pressure on the public fisc. Public spending amounted to 44.8% of GDP in 2013, which is still too high but down from 46.3% in 2010. The government projects it will fall to 40% by 2017. …Madrid has also made clear that it believes private growth is the real answer to its fiscal woes. …In other words, economic growth spurred by low taxes and less state intervention yields more revenue over time. If Mr. Montoro can pursue the logic of that insight, there’s hope for Spain’s beleaguered economy.

I’m not overly confident about Spain’s future, but it is worth noting that, according to IMF data, government spending has basically been flat since 2010 (after rising by an average of about 10 percent annually in the previous three decades).

So if the politicians can maintain fiscal discipline by following my Golden Rule, maybe Spain can undo decades of profligacy and become the success story of the Mediterranean.

Let’s hope so. In any event, we know some Spanish taxpayers have decided that they’re tired of being fleeced.

We have one final example of the IMF’s compulsive tax-aholic instincts.

Allister Heath explains that the bureaucracy is pushing for a plethora of new taxes on the U.K. economy.

The IMF wants an increase in the VAT burden.

…the IMF wants to get rid or significantly reduce the zero-rated exemption on VAT, which covers food, children’s clothes and the rest. While it is true that the exemptions reduce economic efficiency, ditching them would necessitate a big hike in benefits and a major uplift in the minimum wage, which would be far more damaging to the economy’s performance and ability to create jobs for the low-skilled. It’s a stupid idea and one which would destroy any government that sought to implement it, with zero real net benefit. It would be a horrendous waste of precious political capital that ought instead to be invested in real reform of the public sector.

And an increase in energy taxes.

The report also calls for a greater reliance on so-called Pigouvian taxes, which are supposed to discourage externalities and behaviour which inflicts costs on others. It mentions higher taxes on carbon and on congestion as examples. But what this really means is that the IMF is advocating a massive tax increase on motorists, even though there is robust evidence which suggests that they already pay much more, in the aggregate, than any sensible measure of the combined cost of road upkeep and development, pollution and congestion.

And higher property taxes.

It gets worse: these days, one cannot read a document from an international body that doesn’t call for greater taxes on property. This war on homeowners is based on the faulty notion that taxing people who own their homes doesn’t affect their behaviour, which is clearly ridiculous. This latest missive from the IMF doesn’t disappoint on this front: it calls for the revaluation of property for tax purposes, which is code for a massive increase in council tax for millions of homes, especially in London and the home counties.

Understandably, Allister is not thrilled by the IMF’s proposed tax orgy.

The tax burden is already too high; increasing it further would be a terrible mistake. The problem is that spending still accounts for an excessively large share of the economy, and the political challenge is to find a way of re-engineering the welfare state to allow the state to shrink and the private sector to expand. The model should be Australia, Switzerland or Singapore, countries that boast low taxes and high quality services.

And I particularly like that Allister correctly pinpoints the main flaw in the IMF’s thinking. The bureaucrats look at deficits and they instinctively think about how to close the gap with tax hikes.

That’s flawed from a practical perspective, both because of the Laffer Curve and because politicians will respond to the expectation of higher revenue by boosting spending.

But it’s also flawed from a theoretical perspective because the real problem is that the public sector is far too large in all developed nations. So replacing debt-financed spending with tax-financed spending doesn’t address the real problem(even if one heroically assumes revenues actually materialize and further assumes politicians didn’t exacerbate the problem with more spending).

Here’s a remedial course for politicians, international bureaucrats, and others who don’t understand fiscal policy.