When asked about the most worrisome statistic for a nation, I don’t say it’s the top marginal tax rate, even though I think class-warfare taxation is very poisonous for long-run economic performance.

Nor do I say it’s the burden of government spending relative to private economic output, even though the size of the public sector gives us a good idea of the degree to which labor and capital are being poorly allocated.

I don’t even say that a nation’s score in the Economic Freedom of the World index is the most important number, even though that’s the best and most comprehensive measure of the quality of a country’s economic policy.

My answer, for what it’s worth, is that a nation is doomed when a majority of its people decide that it is morally and economically okay to live off the labor of others and want to use the coercive power of government to make it happen.

For lack of a better term, we can call this a country’s Dependency Ratio, and it’s a measure of eroding social capital. To what degree, in other words, has the entitlement mentality replaced the work ethic and the spirit of self reliance?

But before continuing further, I want to provide two important caveats.

1) The Dependency Ratio is not the percentage of households that get money from the government. That’s an important number, to be sure, but it includes people who get money but don’t have an entitlement mentality. A good example is that Social Security recipients in America get checks from Uncle Sam, but only because they had no choice but to pay into the system and did not have the freedom to use that money instead for a personal retirement account. In many if not most cases, they don’t see themselves as part of a “takers” coalition.

2) From a practical perspective, the Dependency Ratio is a good concept, but I’m not aware of a methodologically sound way to calculate a nation’s entitlement mentality. And there’s definitely not good data for purposes of doing international comparisons (though this polling data suggests that the problem is much more severe in nations such as France than it is in the United States). So you have to rely on imperfect proxy measures, such as the share of households getting payments, the size and cost of the bureaucracy, and overall social welfare spending.

I’ve shared all these thoughts because they give the necessary background for today’s main topic, which is South Africa’s dismal economic future.

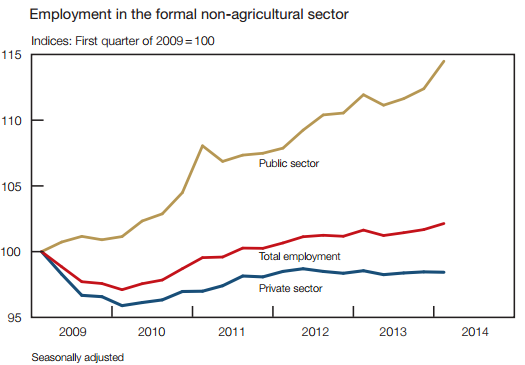

Take a look at this very depressing chart that appeared in my Twitter feed. It shows what has happened over the past five years in South Africa’s labor market.

This isn’t good news. The number of bureaucrats has risen dramatically while there’s been no growth in the number of people working in the economy’s productive sector.

If this trend continues, it’s only a matter of time before South Africa suffers economic collapse. You can’t have an ever-growing class of people living off a non-growing pool of taxpayers.

However, I realize that the chart only shows five years of data, so it could present a misleading view of trends in the country, particularly if there are policy reforms in other areas that might offset the damage of expanding bureaucracy.

So let’s look at other economic sources to confirm whether South Africa is moving in the wrong direction.

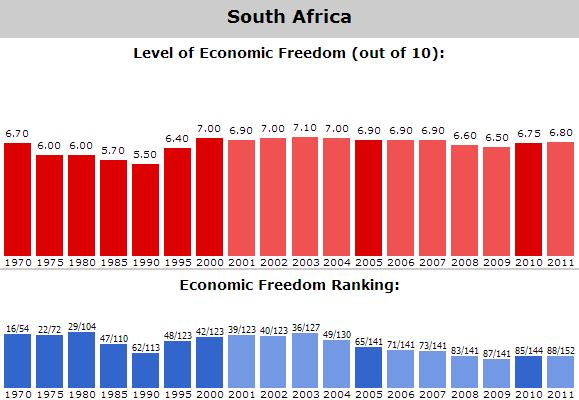

I mentioned above that the Economic Freedom of the World has the best data on the quality of a nation’s economic policy. Here’s South Africa’s performance.

The good news is that South Africa enjoyed a big jump in economic freedom between 1990 and 2000, which isn’t too surprising since the morally abominable Apartheid regime relied on heavy levels of government intervention. Ending that system was a key step in economic liberalization.

But the bad news is that there’s been no improvement since that time. Indeed, South Africa’s score has declined. The fall in the absolute score is minor, but bigger problem is that the nation’s relative score has suffered a big drop. If you look at the blue bars on the bottom, you can see that South Africa had the world’s 36th-freest economy in 2003, but it’s now down to having the world’s 88th-freest economy.

In other words, other nations have moved policy in the right direction while South Africa has been stagnant.

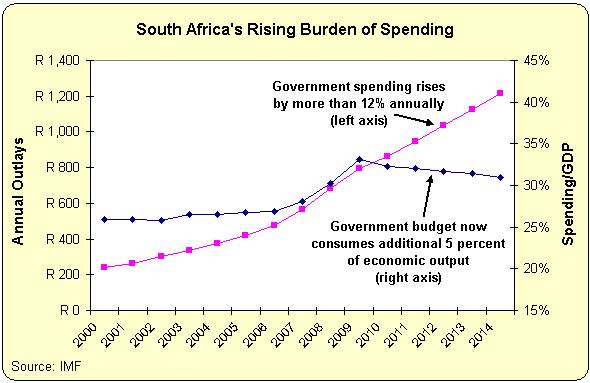

Since I’m a fiscal policy economist, I also looked at what’s been happening to the burden of government spending in South Africa.

As you can see, this chart (based on IMF data) shows that government outlays (left axis) have jumped significantly since the turn of the century.

And since government grew faster than the private sector (violating the Golden Rule), the overall burden of government spending increased (right axis) even when measured as a share of economic output.

I don’t know if the additional spending has been used to pay for additional bureaucrats, social welfare programs, infrastructure, education, or the military.

I suspect all of the above, which helps to explain why South Africa’s fiscal policy score from Economic Freedom of the World has dropped from 6.45 to 5.45 (on a 1-10 scale) since 2000.

More important, I also suspect that the net result is to have lured lots of additional people into government dependency.

That doesn’t bode well for South Africa’s future.