Genuine tax reform would be the second-best fiscal policy reform to boost economic growth.*

With a simple and fair tax system, we could get rid of high tax rates that penalize productive behavior. We could eliminate the double taxation that discourages saving and investment. And we could wipe out the rat’s nest of deductions, credits, exemptions, preferences, exclusions, and other loopholes that bribe people into making economically unwise decisions.

When pushing for tax reform, I normally cite the flat tax, but there are many roads that lead to Rome. I’ve also pointed out that other tax reform plans have similar attributes. Here’s what I wrote, for instance, when comparing the flat tax and national sales tax.

In simple terms, a national sales tax (such as the Fair Tax) is like a flat tax but with a different collection point. …the two plans are different sides of the same coin. The only difference is that the flat tax takes of slice of your income as you earn it and the sales tax takes a slice of your income as you spend it. But neither plan has any double taxation of income that is saved and invested. And neither plan has loopholes to lure people into making economically irrational decisions.

And even though I’m so hostile to the value-added tax that I almost foam at the mouth, I’ve even acknowledged that it would be a good system if you could somehow permanently eliminate all taxes on income.

…like the flat tax and national sales tax, it’s a single-rate system with no double taxation of income that is saved and invested

Some folks think my ecumenical attitude about tax reform is misguided. They argue, from a political perspective, that we won’t make progress unless we unify behind one plan.

That’s probably true at some point in the future, but I would argue that we first need discussion and debate about the principles of tax reform.

And that’s why I’m happy to see that the Heritage Foundation has published a new paper, authored by David Burton, that explains why the major tax reform plans are economically interchangeable.

The four leading conservative tax reform plans are the Hall–Rabushka flat tax, the new flat tax, a national sales tax, and a business transfer tax. Each is a consumption tax with an equivalent tax base. Except for secondary design choices and the choice of which taxes to replace, each would apply the same tax rate to raise a given amount of tax revenue. They would also have the same economic effects. The choice among them, therefore, rests on non-economic grounds.

Perhaps the most important part of that excerpt is where David asserts that all of the big tax reform proposals are consumption taxes.

This point deserves some elaboration. Here’s some of what I wrote on this same issue.

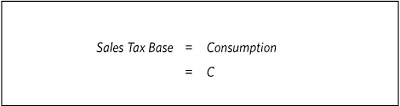

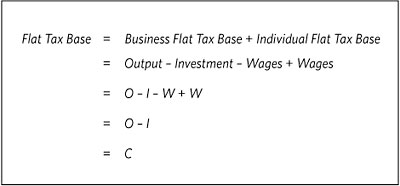

For all intents and purposes, a “consumption tax” is any system that avoids the mistake of double-taxing income that is saved and invested. Both the national sales tax and the value-added tax, for instance, are examples of consumption-based tax systems. But the flat tax also is a consumption tax. It isn’t collected at the cash register like a sales tax, but it has the same “tax base.”

Another way of saying the same thing it to point out that a “consumption tax” is simply a system where income is taxed only one time.

And that’s also true of the subtraction-method VAT, which David refers to as a BTT, along with the “new flat tax,” which is similar to the traditional flat tax except for the method used to prevent double taxation.

In his paper, David has some flowcharts to illustrate the similarities of the various tax reform plans.

Here’s the one for a national sales tax.

And here’s the one for the flat tax.

Let’s close by reminding ourselves about what’s wrong with the current system. Here’s a video produced by Professor Murray Sabrin at Ramapo College in New Jersey. I make a few appearances, beginning about 10-1/2 minutes into the film.

*The best fiscal policy reform would be dramatically shrinking the size of the federal government so that a far greater share of labor and capital in our economy could be allocated by market forces rather than by politicians and bureaucrats. Ideally, the federal government could be reduced to the limited “night watchman” functions envisioned by the Founding Fathers, in which case there would be no need for any broad-based tax.