When I wrote last week about “social capital” as a key determinant of long-run prosperity, I didn’t realize I would generate a lot of feedback. Including several requests for more information.

Which creates a small problem since the field is so large that it’s difficult to provide an overview.

If people were asking questions on the flat tax, Laffer Curve, or the economic impact of government spending, I could give succinct and targeted responses. On the topic of social capital, by contrast, I almost don’t know where to start.

The first thing I should say is that scholars have been addressing these issues for centuries, even if in some cases they didn’t use the phrase “social capital” and instead talked about tradition, culture, ethics, morality, or civic attitudes.

Many people know Adam Smith wrote An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, but he also wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments in the 1700s, and that book deals with issues relating to social capital.

Or consider the work of Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote about social capital in Democracy in America in the 1800s. More recently, in the 1970s, Friedrich Hayek discussed ethics and attitudes as part of his three-volume masterpiece on Law, Legislation, and Liberty.

Moving into the 21st Century, the issue of “culture” and economics also was the subject of an in-depth online symposium at the Cato Institute in 2006. Here’s some of what Lawrence Harrison wrote.

Some economists have confronted culture and found it helpful in understanding economic development. Perhaps the broadest statement comes from the pen of David Landes: “Max Weber was right. If we learn anything from the history of economic development, it is that culture makes almost all the difference.” Elaborating on Landes’s theme, Japanese economist Yoshihara Kunio writes, “One reason Japan developed is that it had a culture suitable for it. The Japanese attached importance to (1) material pursuits; (2) hard work; (3) saving for the future; (4) investment in education; and (5) community values.” …More broadly, the analysis of religions suggests that Protestant, Jewish, and Confucian societies do better than Catholic, Islamic, and Orthodox Christian societies because they substantially share the progress-prone Economic Behavior values of the typology whereas the lagging religions tend toward the progress-resistant values. Symbolic of this divide is the persistent ambivalence of the Catholic Church toward market economics… But religion is not the only source of progress-prone economic behavior: the Basques are highly entrepreneurial and highly Catholic; and Chile, boasting the most successful sustained economic performance in Latin America, is also the most Catholic.

And here are portions of Gregory Clark’s contribution.

The standard economist emphasizes that stability, incentives, and laissez-faire are all the magic needed for riches. …attempts to introduce culture into economic discussions so far have been generally either ad hoc, vacuous, blatantly false, or void of testability. …Weber, as is well known, thought that certain types of Protestant ideology were conducive to economic growth. …The Catholics of modern southern Germany, however, would think they have a thing or two to teach their Protestant compatriots of the north about the virtues of hard work and self-reliance. The dour and thrifty Calvinists of my native Scotland look with envy now at the successes of the Catholic Irish, and ask how they can emulate this.…Protestants on average may have values associated with economic growth, but that seems to have nothing to do with their specific theology. Lawrence Harrison may seem to escape some of this problem of identifying cultural variation by using a survey of 25 factors that purports to identify systematically the essential elements of cultures that promote high incomes and growth: universal progress cultures. He divides cultures into the “progress-prone” and the “progress-resistant.” In progress-prone societies, for example, people assert “I can influence my destiny.” In progress-resistant societies “fatalism” rules. Progress-prone societies have better economic performance. …The problem with both the Harrison and McClelland approaches is that the responses may reflect just the realities of the institutional framework people live within, rather than their cultural attitudes. A North Korean who reports “fatalism” or “resignation” is plausibly no different culturally from a South Korean who states “I can influence my destiny.”

My grad school classmate and now Professor Pete Boettke adds his two cents.

…we do need to have market prices to allocate resources efficiently. The “getting the prices right” mantra is not wrong, just incomplete. In order to get market prices, we do need to have private property rights and the enforcement of contracts. The “getting the institutions in place” mantra isn’t wrong either. Many of the significant advances in political economy during the 1990s, when the problems of socialist transition were at the forefront of professional and public policy attention, were related to a change of emphasis from “getting the prices right” to “getting the institutions in place.” …In economic terms, culture is a tool for the self-regulation of behavior, and as such it either lowers or raises the costs of enforcing the rules of the game. A free society works best when the need for policemen is least. If the rules of conduct correlated with high levels of economic well-being are viewed by a culture as illegitimate, then those rules will be violated unless there are strong monitors. The costs of monitoring may be so high that the social order cannot in fact be sustained. …Scholars such as Joel Moykr in The Levers of Riches have documented the great technological innovations that fueled growth during the Industrial Revolution, but Mokyr also documents the underlying belief systems and attitudes that had to be present for those innovations to be discovered, implemented, and put into common practice. Without that underlying cultural commitment to scientific discovery, innovation would have been stifled. We can say the same for beliefs and attitudes that undermine private property, mutually beneficial exchange, and commercial development. …Whatever advantages a culture may have, they will not be realized under bad institutions. And whatever disadvantages a culture may have, they will slowly erode, and the culture will improve, when people get to live under institutions of political and economic freedom. Culture can act as a constraint, but it is also a malleable constraint.

James Robinson uses China and Chile as examples that suggest good policies and institutions are key.

If the Chinese do well in Indonesia because they have such a good culture, then why is China one of the world’s poorest countries? …surely the culture which supposedly is conducive to prosperity in China is an old one and long predates the acceleration of growth which took place in the late 1970s. …culture was held constant and institutions and policies changed while growth accelerated. From this it seems to follow that the reasons countries are poor has nothing to do with culture but rather policies and institutions that do not create the right incentive environment. …What about Chile, the one Latin American success story? Lawrence Harrison argues that Chile has a unique culture, but then why did it manifest itself so recently? It is only since the mid-1980s that the growth path of Chile has distinguished it from other Latin American countries. …culture might matter, but doubters like me will not be convinced by the evidence here.

But this topic gets attention at places other than libertarian think tanks.

Here are some excerpts from a World Bank study looking at the degree to which culture matters for development.

In the abstract there is no doubt a general acceptance that a particular work ethic, a system of personal values and attitudes must have a role in guiding a population along a particular development path; indeed, how could it be otherwise? …Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (2006) conducted a regression analysis combining survey and macroeconomic data across 53 countries and found that “a 10 percentage point increase in the share of people who think thriftiness is a value that should be taught to children is linked to a 1.3 percentage point increase in the national saving rate”. Tabellini (2010) also showed that European regions with a stronger belief in individual effort tend to have higher GDP per capita and GDP growth. …Lee Kuan Yew speaks of a set of values—“thrift, hard work, filial piety and loyalty to the extended family, and, most of all, the respect for scholarship and learning”—as having provided a powerful cultural backdrop for the development of East Asian countries… Max Weber famously made the case about the role of culture in development in his essay “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,” arguing that Protestantism promoted the rise of modern capitalism “by defining and sanctioning an ethic of everyday behavior that conduced to business success” comprising “hard work, honesty, seriousness, the thrifty use of money and time.

Last but not least, let’s consider some practical applications based on a recently published New York Times column by David Brooks.

Twenty-five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the biggest surprise is how badly most of the post-communist nations have done since. …In the bottom group are basket-case nations that haven’t even recovered the level of real income they had in 1990, as measured by real G.D.P. per capita. These failures include Ukraine, Georgia, Bosnia, Serbia and others — about 20 percent of the post-communist world. “Basically,” Milanovic writes, these “are countries with at least three to four wasted generations. …The next group includes those nations that are merely moderate failures, with per capita economic growth rates under 1.7 percent a year. These are nations like Russia and Hungary that continue to fall steadily behind the West — about 40 percent of the post-communist world by population. The third group includes those with growth rates between 1.7 percent and 1.9 percent. These countries, like the Czech Republic and Slovenia, are holding steady with the capitalist world. Finally there are the successes, the nations that are catching up. …There are only five countries that have emerged as successful capitalist economies: Albania, Poland, Belarus, Armenia and Estonia. To put it another way, only 10 percent of the people living in post-communist nations are living in a place that successfully made the transition to capitalism.

I wouldn’t necessarily have listed Albania and Belarus as success stories, but it’s certainly true that the countries that comprised the former Soviet Bloc have seen a lot of divergence.

Heck, check out this graph comparing Ukraine and Poland if you want a remarkable example.

The question is why did they behave differently?

Why did some countries succeed while others failed? First, leaders in some countries simply made better political decisions. Most of these countries enacted economic reforms, like deregulating prices and privatizing nationalized companies. Some nations like Estonia and Poland enacted reforms radically and quickly… The quick and radical group saw a slightly bigger output drop over the near term but much more prosperity over the long run. …Finally, and most important, there is the level of values. A nation’s economy is nestled in its moral ecology. Economic performance is tied to history, culture and psychology. …[Some] countries lacked this cultural brew. Worse, life was marked by fear, by arbitrary power, by suspicion that people are watching you, by distrust. People raised in this atmosphere of distrust have trouble forming companies and associations. They are more likely to be driven by a grab-what-you-can logic — a culture of corruption and appropriation. …The lesson of the past 25 years is that democratic prosperity is built on layers of small achievements 10,000 fathoms deep. Communism ripped at all that bottom-up society-making and damaged the psyches of its victims. Healing from those wounds is gradual.

So what’s the bottom line?

I’m not really sure, other than to assert that we will never triumph over statism if Americans think it is morally acceptable to live off their neighbors via the coercive power of government.

In many of my fiscal policy speeches, I explain that we face a major crisis because of demographics and poorly designed entitlement programs, but then tell audiences that we can solve the problem with structural program reforms.

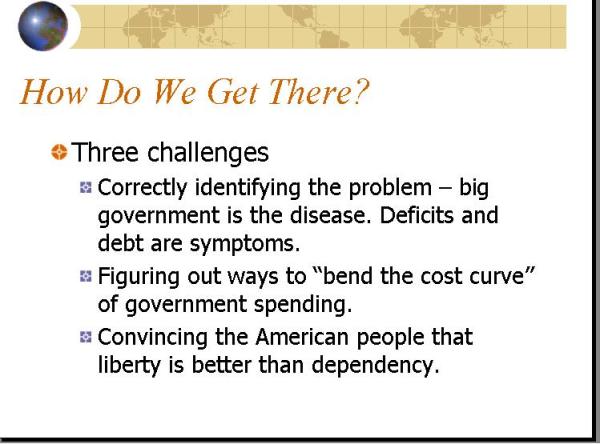

To wrap things up, I often close with this Powerpoint slide. As you can see, the first two themes are very familiar to regular readers. Our problem is too much government spending and the solution is my Golden Rule of spending restraint.

But the third bullet point is really about social capital.

In other words, we can share all sorts of evidence about how some nations grow faster with small government and free markets.

We can also highlight how statist policies slow growth.

But none of those arguments will mean much in the long run if people prefer to be wards of the state.