I don’t know whether it’s because I’m a libertarian or because I’m an economist, but I get very frustrated by the issue of corporate inversions.

It galls me to hear demagogic politicians like Obama make absurd statements about “unpatriotic” corporations that re-domicile overseas when the problem is entirely the result of bad policy that penalizes U.S.-domiciled firms trying to compete in global markets.

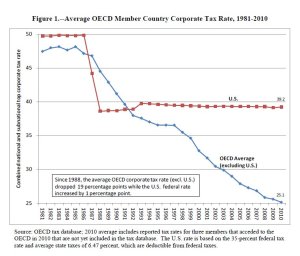

- The United States imposes the world’s highest corporate tax rate.

- The United States is one of the few countries to impose “worldwide tax” on domestic firms.

- The United States maintains very anti-competitive tax rules.

So when politicians grouse about “Benedict Arnold” companies, my reaction is to be happy that companies are taking steps to protect workers, consumers, and shareholders.

But, given what he’s done on amnesty and Obamacare, you won’t be surprised to learn that the President has unilaterally changed policy to make inversions more difficult.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that the President’s bad policy doesn’t change reality.

An editorial in the Wall Street Journal looks at the latest example of an American company getting a new address.

Ireland-based drug company Actavis on Monday announced a $66 billion agreement to buy California’s Allergan , maker of the Botox anti-wrinkle treatment. …the tax savings…could be hundreds of millions a year beginning in 2015.

The folks at the WSJ make the obvious point about bad American tax laws.

…the deal highlights how desperately U.S. tax policy needs a makeover. …As if a combined state and local corporate tax rate of 40%—the highest in the industrialized world—isn’t harsh enough, the U.S. is also one of the few countries in which the government demands to be paid even on earnings that have already been taxed in foreign jurisdictions. Given this competitive disadvantage for U.S.-based firms, it’s no coincidence that both of the suitors that have been seeking to acquire Allergan are based overseas.

And what’s really remarkable is that both the suitors used to be U.S.-based companies!

Both Actavis and Valeant used to be based in the U.S. but moved their headquarters offshore in so-called inversion transactions in which they adopted the home country of businesses they acquired. Moving offshore allows businesses to invest more in the U.S., as Actavis has already done with its recent purchase of New York’s Forest Laboratories.

But hold on a second, didn’t the Obama Administration enact rules to prevent inversions?

President Obama views such rational decisions as unpatriotic, because he wants to tax both foreign and U.S. operations. So this fall Treasury Secretary Jack Lew reinterpreted longstanding tax regulations to make it more expensive to execute such deals—a punishment for companies that didn’t exit the U.S. when they had the chance. …Mr. Lew has decided the best response to foreign tax competition is to bolt the door to prevent more corporate escapes.

But here’s the catch. The White House and Treasury Department did make it more costly for companies to re-domicile, but the Administration can’t actually prohibit cross-border mergers.

So let’s summarize the net effect.

Before the Obama Administration imposed new rules, American-based companies would acquire foreign-based companies and use that maneuver to technically re-domicile in a nation with less punitive corporate taxation. But there’s very little risk of American jobs being lost.

After the rule changes, American-based companies are the ones being acquired by their overseas competitors. This means the White House can’t argue that the change in domicile isn’t real. And it means that there’s a far higher probability of jobs going overseas.

I guess the White House thinks this is a victory.

Let’s now step back and put this issue in context. This is the educational part of today’s column.

Here are some slides from a presentation by Professor Dick Harvey at Villanova University School of Law. He presents lots of information, but here are the three slides that are probably most interesting to non-tax geeks.

First, here’s the key thing to know about inversions. They’re a do-it-yourself version of territorial taxation.

And since territorial taxation is the right policy, nobody should be upset about inversions.

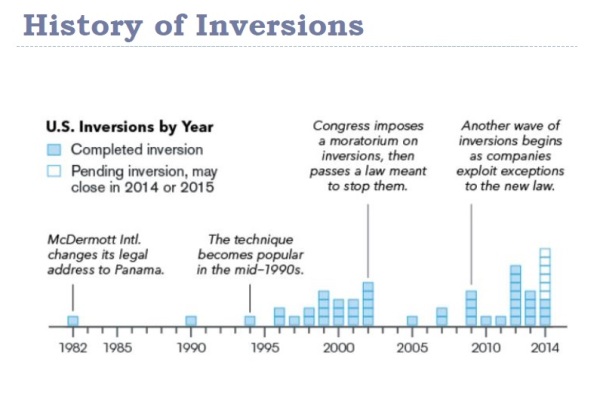

Second, here’s a look at how many inversions occur each year. As you can see, we’re in the midst of another wave.

You’ll notice that these waves roughly coincide with periods featuring corporate tax rate reductions in other nations.

So the lesson is that bad American policy is making it more and more difficult for U.S.-domiciled firms to compete in global markets.

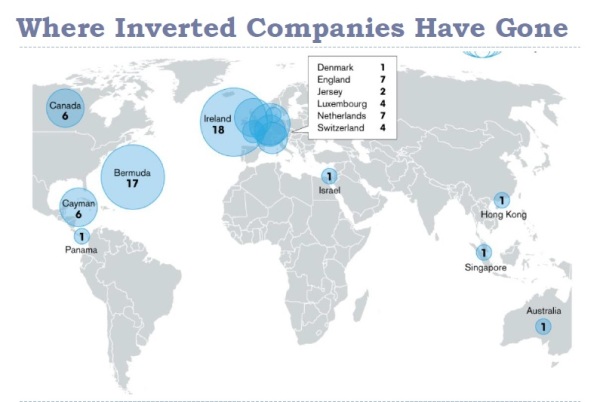

Third, here’s a slide showing where companies are re-domiciling.

Some of my favorite places, particularly Cayman, Bermuda, Switzerland, andHong Kong!

Now let’s zoom out even further and consider the leftist view that multinational corporations are getting away with some sort of scam because of so-called stateless income.

Sinclair Davidson, a professor at Australia’s RMIT University, writes about the issue. Here are a few excerpts from his scholarly paper.

It is commonly argued that the corporate income tax system is ‘broken’. …The latest theoretical argument suggesting that the corporate income tax base is likely to be eroded is the ‘stateless income doctrine’.

But there’s an itsy-bitsy problem with this theory, as Sinclair explains.

…there is no evidence to support the view that the corporate income tax base is being eroded. At best, the concern about the tax base is not so much that it is being eroded, but rather that multinational corporations do not pay tax in every host economy.

He also points out that companies are obeying the law, which is a point I’ve also made on this topic.

…there is little evidence of any wrongdoing by any of the three corporations that are regularly singled out for abuse. It is true that these corporations do not pay as much tax in the UK or the US as those governments would like them to pay, but they pay as much tax as is required by the laws that those governments have passed. …‘None of this required a Senate “investigation” to discover because Apple is constantly inspected by the IRS and other tax authorities. These tax collectors are well aware of Apple’s corporate structure, which has remained essentially the same since 1980. An Apple executive said Tuesday that the company’s annual US tax return adds up to a stack of paperwork more than two feet high. …These corporations are fully compliant with the tax law in the jurisdictions in which they operate.

So what’s his bottom line?

There is no such thing as ‘stateless income’, rather there is income that the governments of the UK and the US do not tax because under their own legal systems that income is not sourced in their economy. When these governments complain about stateless income, the question rather should be, ‘Why do the owners of intellectual property not locate their property in your economy?’. An implicit assumption of the stateless income doctrine is that multinational corporations maximise their value to society only when they pay tax. Of course, this is not the case. … It is one thing to point out that multinational corporations do not pay tax in some jurisdictions but that says nothing about the actual corporate income tax base. … So-called ‘stateless income’ is a return on intellectual property.

Amen.

Let’s close with another perspective on the issue. Stewart Dompe and Adam Smith of Johnson and Wales University in North Carolina have a column in The Freeman.

…the United States is unique in that it taxes corporations at 35 percent regardless of where the income is earned, and hence regardless of whether the corporation benefited from any public goods. Payment without benefit is simply bad business. Avoiding particularly high tax rates like those of the United States can yield significant savings for companies—and their shareholders. Charlotte-based Chiquita Brands International, for instance, hopes to save $60 million via its recent acquisition of Ireland-based Fyffes PLC. Burger King’s merger, according to analyst estimates, could cut its overall tax bill by 13 percent. …Populist themes like “economic patriotism” may appeal to voters, but such arguments are nonsensical: Firms are ultimately responsible to their shareholders. As Judge Learned Hand wrote, “Any one may so arrange his affairs that his taxes shall be as low as possible; he is not bound to choose that pattern which will best pay the Treasury; there is not even a patriotic duty to increase one’s taxes.” If anything, firms have a moral responsibility to minimize their taxable liabilities. The legal structure of a firm establishes the relationship between shareholders, who own the capital, and managers that make operating decisions. Executives have a fiduciary responsibility to pay the lowest tax possible because they are the stewards of their shareholders’ wealth.

I particularly like their conclusion.

This competition among legal regimes is a powerful constraint on government—and that is a good thing for all of us. America has the second-highest corporate tax rate in the world—the highest when state taxes are included. The solution to this problem lies not in closing loopholes or imitating poor Oliver pleading for more, but in offering a simpler, more competitive tax system.

They hit the nail on the head. As I argued just yesterday, we need to restrain the greed of the political class.

But the fight isn’t limited to national capitals. International bureaucracies such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development also are promoting schemes to squeeze more money out of companies – which, of course, means harming workers, consumers, and shareholders.

The pro-tax crowd can concoct all sorts of theories, such as stateless income, but this assault on companies is happening because government have spent themselves into a fiscal ditch and they want taxpayers to pay the price for this profligacy.