Back in 2010, I shared some wise words from Walter Williams and Theodore Dalrymple about how society can become unstable when people figure they can “vote themselves money.”

On a related note, I shared the famous “riding in the wagon” cartoons in 2011 and the “Danish party boat” image in 2014. Both of these posts highlighted the danger that exists when societies reach a tipping point, which occurs when too many people vote themselves into dependency and expect (and vote) for never-ending handouts.

Indeed, this is why I’m very pessimistic about the future of welfare states such as Greece.

And, depending what happens in an upcoming run-off election, I probably won’t be very optimistic about Brazil.

Investor’s Business Daily has shared some fascinating – and disturbing – data from that country’s recent election.

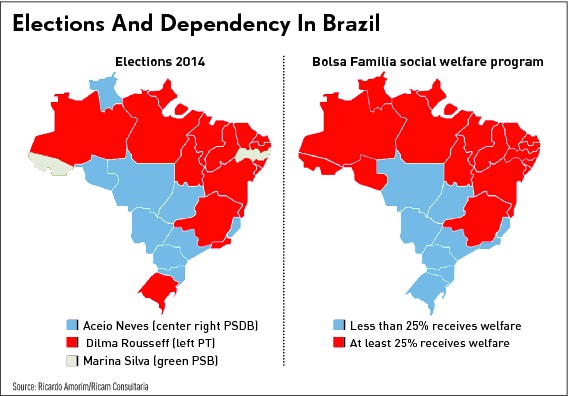

A Brazilian economist has shown a near-exact correlation between last Sunday’s presidential election voting choices and each state’s welfare ratios. Sure enough, handouts are the lifeblood of the left. …Neves won 34% of the vote, Rousseff took 42% and green party candidate Marina Silva took about 20% — and on Thursday, Silva endorsed Neves, making it a contest of free-market ideas vs. big-government statism. But what’s even more telling is an old story — shown in an infographic by popular Brazilian economist Ricardo Amorim. …Amorim showed a near-exact correlation among Brazil’s states’ welfare dependency and their votes for leftist Workers Party incumbent Rousseff. Virtually every state that went for Rousseff has at least 25% of the population dependent on Brazil’s Bolsa Familia welfare program of cash for single mothers… States with less than 25% of the population on Bolsa Familia overwhelmingly went for Neves and his policies of growth. …Fact is, the left cannot survive without a vast class of dependents. And once in, dependents have difficulty getting out.So Brazil’s election may come down to a question of whether it wants to be a an economic powerhouse — or a handout republic.

Here’s the map from IBD showing the close link between votes for the left-wing candidate and the extent of welfare dependency.

It’s not a 100 percent overlap, but the relationship is very strong.

Sort of like the maps I shared on language and voting in Ukraine.

That being said, I’m a policy wonk who wants economic liberty, not a political hack with partisan motives. So let’s look at the implications of growing dependency.

As IBD explains, the greatest risk is that people get trapped in dependency. We see that in advanced nations like the United States and United Kingdom (and the Nordic nations) so is it any surprise that it’s also a problem in a developing country like Brazil (or South Africa)?

Problem is, “some experts warn that a wide majority cannot get out of this dependence relationship with the government,” as the U.K. Guardian put it. And whether it’s best for a country that aspires to become a global economic powerhouse to have a quarter of the population — 50 million people — dependent on welfare and producing nothing is questionable.

I especially appreciate the last part of this excerpt. Economic output is a function of how capital and labor are productively utilized.

In other words, a welfare state imposes a human cost and an economic cost.

Now let’s consider possible implications for the United States. A few years ago, I put together a “Moocher Index” to show which states had the highest percentage of non-poor households receiving some form of redistribution.

Do the moocher states vote for leftists? Well, it we use the 2012 presidential election as a guidepost, 7 of the top 10 moocher states voted for Obama. That suggests that there is a relationship.

But if you look at the states with the lowest levels of dependency, they were evenly split, with 5 for Obama and 5 for Romney. So perhaps there aren’t any big lessons for America, though Obama’s margins in Ohio, Florida, Virginia, Colorado, and Nevada were relatively small.

For what it’s worth, I’m far more worried about these economic numbers, not the aforementioned political numbers.