I confess that I get a bit of perverse pleasure when a left-leaning media outlet screws up and inadvertently shares information that helps the cause of limited government.

A New York Times columnist, for instance, pushed for a tax-hiking fiscal agreement back in 2011 based on a chart showing that the only successful budget deal was the one that cut taxes.

The following year, another New York Times columnist accidentally demonstrated that politicians are trying to curtail tax competition because they want to increase overall tax burdens.

Now it’s happened again.

In a major story on the pension system in the Netherlands, the New York Times inadvertently acknowledged that genuine private savings is the best route to obtain a secure retirement.

Let’s look at a few excerpts, starting with some very strong praise for the Netherlands in the article.

Imagine a place where pensions were not an ever-deepening quagmire, where the numbers told the whole story and where workers could count on a decent retirement. …That place might just be the Netherlands. And it could provide an example for America… “The rest of the world sort of laughs at the United States — how can a great country like the United States get so many things wrong?” said Keith Ambachtsheer, a Dutch pension specialist who works at the University of Toronto… The Dutch system rests on the idea that each generation should pay its own costs — and that the costs must be measured accurately if that is to happen. …The Dutch approach bears little resemblance to the American practice of shielding the current generation of workers, retirees and taxpayers while pushing costs and risks into the future, where they can metastasize unseen.

Interestingly, the article doesn’t explain what makes the Dutch system so superior to its American counterpart, but the phrase “each generation should pay its own costs” is a big hint.

That basically means that the system is not based on inter-generational redistribution, which is a core feature of pay-as-you-go schemes such asAmerica’s bankrupt Social Security system.

That’s important, but what’s really key is that the Dutch system is based on private savings and private investment. It’s not a pure libertarian system, to be sure, since there are government mandates (such as high mandatory savings to finance generous old-age payments), but it is definitely a far more market-based system than what we have in America.

Here are some details.

About 90 percent of Dutch workers earn real pensions at their jobs. Their benefits are intended to amount to about 70 percent of their lifetime average pay… For this and other reasons, the Netherlands has for years been at or near the top of global pension rankings compiled by Mercer, the consulting firm, and the Australian Center for Financial Studies, among others. Accomplishing this feat — solid workplace pensions for most citizens — isn’t easy. For one thing, it’s expensive. Dutch workers typically sock away nearly 18 percent of their pay, most of it in diversified, professionally run pension funds. That compares with 16.4 percent for American workers, but most of that is for Social Security, which is intended to provide just 40 percent of a middle-class worker’s income in retirement.

And it’s worth noting that a system based on private savings also means that there is lots of money that can be invested.

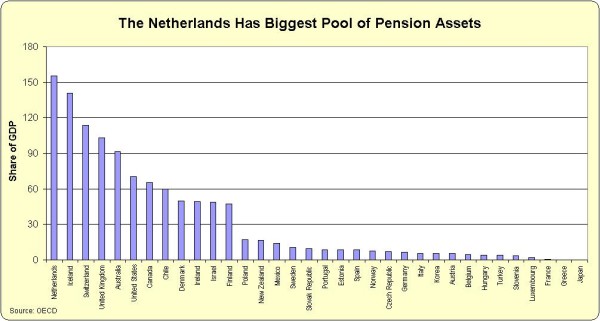

And “lots of money” isn’t just a throwaway line. The Netherlands leads the OECD in private pension assets, measured as a share of economic output.

It’s worth pointing out, by the way, that the leading nations in this chart (Chile, Iceland, Australia, Switzerland, and Denmark) generally have systems based at least in part on private mandatory savings.

And given that big piles of money are very tempting targets for greedy governments, it’s also worth noting that the Dutch haven’t allowed the system to get politicized.

There’s not the slightest whisper of a rumor, for instance, that the government will grab the money.

Moreover, unlike the United States (particularly when discussing the pension systems operated by state and local governments), pension funds actually have to maintain adequate assets to pay promised benefits.

And no using funky math!

Imagine a place where regulators existed to make sure everyone followed the rules. …standing guard over it is a decidedly capitalist watchdog, the Dutch central bank. …the central bank in 2002 began to require pension funds to keep at least $1.05 on hand for every dollar they would have to pay in future benefits. If a fund fell below the line, it had just three years to recover. …The Dutch central bank also imposed a rigorous method for measuring the current value of all pensions due in the future. …Notably, the Dutch central bank prohibited the measurement method that virtually all American states and cities use, which is based on the hope that strong market gains on pension investments will make the benefits cheaper. …He explained that in the Netherlands, regulators believe that basing the cost of benefits today on possible investment gains tomorrow is the same as robbing tomorrow’s workers to pay for today’s excesses.

No wonder the Netherlands ranks so much higher than the United States in the rule of law index.

Now that I’ve said what’s good about the system, I’ll be the first to admit that it could be improved.

First and foremost, the Dutch system is basically a near-universal defined-benefits regime, which means that workers get a guaranteed amount of money and it is up to the fund administrator to make sure there is enough money.

This type of system has been very unstable in the United States because of chronic underfunding. The Dutch so far seem to have avoided that problem, but I still prefer the defined-contribution systems, which means that workers get back exactly what they paid in, plus all the earnings.

And the good news, from this perspective, is that the Dutch are moving in this direction according to a British service that monitors global pension developments.

Occupational pension schemes in the Netherlands are still mostly defined benefit (DB) schemes. But as companies are seeking to control costs and risk, a massive shift from final salary career average plans is taking place. Also, the popularity of defined contribution (DC) and hybrid schemes is growing.

One thing I wouldn’t change about the Dutch system is the tax treatment. The Dutch have what is sometimes called an exempt-exempt-tax (EET) system, which is sort of like a traditional IRA (i.e., no double taxation).

The Dutch government explains that the income is taxed only one time.

No tax is levied on pension contributions. And the growth of pension rights via the pension fund’s investment performance remains untaxed. Pension benefit is only taxed when it is received.

And let’s hope it stays that way, though the welfare state in the Netherlands is so large that the nation does have some significant long-run fiscal challenges. And that could lead future politicians to sacrifice the stability of the private pension system in order to prop up big government.

That being said, I would gladly trade the U.S. Social Security system for the Dutch mandatory pension system. An imperfect system based on private savings is always a better bet than a perfectly terrible tax-and-transfer scheme.

For more information, here’s the video I narrated explaining why personal retirement accounts are far superior to government-run schemes such as Social Security.