There’s an old saying that there’s no such thing as bad publicity.

That may be true if you’re in Hollywood and visibility is a key to long-run earnings.

But in the world of public policy, you don’t want to be a punching bag. And that describes my role in a book excerpt just published by Salon.

Jordan Ellenberg, a mathematics professor at the University of Wisconsin, has decided that I’m a “linear” thinker.

Here are some excerpts from the article, starting with his perception of my view on the appropriate size of government, presumably culled from this blog post.

Daniel J. Mitchell of the libertarian Cato Institute posted a blog entry with the provocative title: “Why Is Obama Trying to Make America More Like

Sweden when Swedes Are Trying to Be Less Like Sweden?” Good question! When you put it that way, it does seem pretty perverse. …Here’s what the world looks like to the Cato Institute… Don’t worry about exactly how we’re quantifying these things. The point is just this: according to the chart, the more Swedish you are, the worse off your country is. The Swedes, no fools, have figured this out and are launching their northwestward climb toward free-market prosperity.

I confess that he presents a clever and amusing caricature of my views.

My ideal world of small government and free markets would be a Libertopia, whereas total statism could be characterized as the Black Pit of Socialism.

But Ellenberg’s goal isn’t to merely describe my philosophical yearnings and policy positions. He wants to discredit my viewpoint.

So he suggests an alternative way of looking at the world.

Let me draw the same picture from the point of view of people whose economic views are closer to President Obama’s…

This picture gives very different advice about how Swedish we should be. Where do we find peak prosperity? At a point more Swedish than America, but less Swedish than Sweden. If this picture is right, it makes perfect sense for Obama to beef up our welfare state while the Swedes trim theirs down.

He elaborates, emphasizing the importance of nonlinear thinking.

The difference between the two pictures is the difference between linearity and nonlinearity… The Cato curve is a line; the non-Cato curve, the one with the hump in the middle, is not. …thinking nonlinearly is crucial, because not all curves are lines. A moment of reflection will tell you that the real curves of economics look like the second picture, not the first. They’re nonlinear. Mitchell’s reasoning is an example of false linearity—he’s assuming, without coming right out and saying so, that the course of prosperity is described by the line segment in the first picture, in which case Sweden stripping down its social infrastructure means we should do the same. …you know the linear picture is wrong. Some principle more complicated than “More government bad, less government good” is in effect. …Nonlinear thinking means which way you should go depends on where you already are.

Ellenberg then points out, citing the Laffer Curve, that “the folks at Cato used to understand” the importance of nonlinear analysis.

The irony is that economic conservatives like the folks at Cato used to understand this better than anybody. That second picture I drew up there? …I am not the first person to draw it. It’s called the Laffer curve, and it’s played a central role in Republican economics for almost forty years… if the government vacuums up every cent of the wage you’re paid to show up and teach school, or sell hardware, or middle-manage, why bother doing it? Over on the right edge of the graph, people don’t work at all. Or, if they work, they do so in informal economic niches where the tax collector’s hand can’t reach. The government’s revenue is zero… the curve recording the relationship between tax rate and government revenue cannot be a straight line.

So what’s the bottom line? Am I a linear buffoon, as Ellenberg suggests?

Well, it’s possible I’m a buffoon in some regards, but it’s not correct to pigeonhole me as a simple-minded linear thinker. At least not if the debate is about the proper size of government.

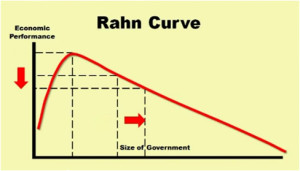

I make this self-serving claim for the simple reason that I’m a big proponents of the Rahn Curve, which is …drum roll please…a nonlinear way of looking at the relationship between the size of government and economic performance. And just in case you think I’m prevaricating, here’s a depiction of the Rahn Curve that was excerpted from my video on that specific topic.

I make this self-serving claim for the simple reason that I’m a big proponents of the Rahn Curve, which is …drum roll please…a nonlinear way of looking at the relationship between the size of government and economic performance. And just in case you think I’m prevaricating, here’s a depiction of the Rahn Curve that was excerpted from my video on that specific topic.

Moreover, if you click on Rahn Curve category of my blog, you’ll find about 20 posts on the topic. And if you type “Rahn Curve” in the search box, you’ll find about twice as many mentions.

So why didn’t Ellenberg notice any of this research?

Beats the heck out of me. Perhaps he made a linear assumption about a supposed lack of nonlinear thinking among libertarians.

In any event, here’s my video on the Rahn Curve so you can judge for yourself.

And if you want information on the topic, here’s a video from Canada and here’sa video from the United Kingdom.

P.S. I would argue that both the United States and Sweden are on the downward-sloping portion of the Rahn Curve, which is sort of what Ellenberg displays on his first graph. Had he been more thorough in his research, though, he would have discovered that I think growth is maximized when the public sector consumes about 10 percent of GDP.

P.P.S. Ellenberg’s second chart puts the U.S. and Sweden at the same level of prosperity. Indeed, it looks like Sweden is a bit higher. That’s certainly not what we see in the international data on living standards. Moreover, Ellenberg may want to apply some nonlinear thinking to the data showing that Swedes in America earn a lot more than Swedes still living in Sweden.