I’m a pessimist about public policy for two simple reasons:

1) Seeking power and votes, elected officials generally can’t resist making short-sighted and politically motivated choices that expand the burden of government.

2) Voters are susceptible to bribery, particularly over time as social capital(the work ethic, spirit of self reliance, etc) erodes and the entitlement mentality takes hold.

Actually, let me add a third reason.

The first two reasons explain why countries get into trouble. Our last reason explains why it’s oftentimes so hard to then fix the mess created by statism.

3) Once a nation adopts big government, reform is difficult because too many voters are riding in the wagon of dependency and they reflexively oppose good policy.

Or they’re riding in the party boat, but you get the idea.

Now that I’ve explained why I’m a Cassandra, let me try to be a Pollyanna.

And I’m going to be Super Pollyanna, because my task is to explain how Greece can be saved.

I’ll start by pointing out that government spending has actually been cut in recent years. And we’re talking about genuine spending cuts, not the make-believe cuts you find in Washington, which occur when spending doesn’t grow as fast as previously planned.

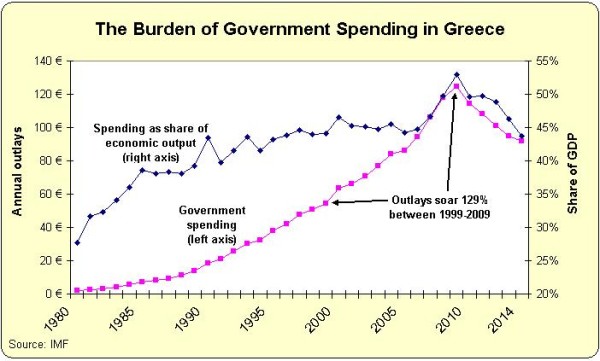

This chart, based on IMF data, shows that the budget increased dramatically in Greece from 1980-2009. But once the fiscal crisis started and Greek politicians no longer had the ability to finance spending with borrowed money, they had no choice but to reduce the burden of government spending.

This seems like great news, but there’s one minor problem and one major problem.

The minor problem is that there hasn’t been nearly enough structural reform of the welfare state in Greece. For long-run fiscal recovery, it’s very important to save money by reducing handouts that create dependency, while also shrinkingthe country’s bloated bureaucracy. By comparison, it’s less important (or perhaps even harmful) to save money by letting physical infrastructure deteriorate.

The major problem is that controlling government spending is just one piece of the puzzle. There are five major factors that determine economic performance, with experts assigning equal importance to fiscal policy, trade policy, regulatory policy, monetary policy, and rule of law.

Moreover, not only is fiscal policy just 20 percent of the puzzle, it’s also important to understand that spending is just part of that 20 percent. You also have to consider the tax burden.

And the progress Greece has made on the spending side of the budget has been offset by a bunch of destructive tax increases.

But there is a glimmer of hope because Greek politicians apparently realize that this is a problem.

Here are some excerpts from the Wall Street Journal’s coverage.

Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras promised tax-relief measures to help jump-start the country’s economy and boost the government’s popularity as it faces a series of political challenges in the months ahead. “The overtaxation has to end,” Mr. Samaras said Saturday during a speech.

It’s easy to see why there’s a desire to boost economic performance.

Since entering recession in 2008, Greece’s economy has shrunk by more than a quarter… This year, however, the country is expected to emerge from recession and post growth of 0.6%. But the recovery has yet to trickle down to ordinary Greeks who continue to face a jobless rate of more than 27% and higher taxes imposed during the past few years.

However, don’t get too excited. The Premier isn’t talking about sweeping reforms.

Instead, it appears that the proposed changes will be very minor.

In his remarks, the Greek premier announced a number of tax changes, including a 30% reduction in the levy on home heating oil and amendments to a new unified property tax that has been so far marred by errors and miscalculations in implementation.

Geesh, talk about rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Indeed, at least one of the tax cuts may be designed to bring in more money for the government. The New York Times, for instance, reports that the energy tax didn’t generate any extra tax revenue.

That levy, which was introduced in 2012, raised the tax on heating oil 450 percent. But it has failed to bring in additional revenue and has led to environmental damage as Greeks turned to burning wood for heat.

I guess it’s progress that both the Greek government and the New York Times are acknowledging the Laffer Curve, but this is a perfect example of why it’s important to be on the growth-maximizing point of the curve rather than the revenue-maximizing point.

So why am I expressing a tiny sliver of optimism when the Greek government’s tax agenda is so timid?

Well, there’s at least some hope of bigger and more pro-growth reforms.

He also announced a reduction to a so-called solidarity tax on income, the size of which is to be determined when the state budget for 2015 is drafted in October. The changes would be part of a “road map” for lowering taxation with cuts to the property tax, income tax and corporate tax to come later, he said. “Overtaxation may have been necessary, but now it must stop,” he said.

And the Greek press is reporting further details indicating that the government wants to reduce marginal tax rates

Samaras said that it his ultimate aim to reduce the top income tax rate to 32 percent and for business to pay no more than 15 percent.

If these policies actually took place, then I suspect Greece’s economy would enjoy robust growth.

Particularly if policy makers also dealt with the major problem of excessive regulation (see here and here to get a flavor of the awful nature of red tape in Greece).

In other words, any nation can prosper if good policy is adopted.

Including Greece, though I must admit in closing that I suspect that there’s a less-than-15-percent chance that my optimistic scenario will materialize. And if you read this Mark Steyn column, you’ll understand why the pessimistic scenario is much more likely.