I’m in Australia for Consilium, an annual conference which is hosted by the Centre for Independent Studies.

I spoke on fiscal policy and pontificated on the need for nations to restrain government spending.

That’s an important message (at least in my humble option), but I thought it was more interesting to learn more about the tax and spending policies of Australia’s current government, which is led by the supposedly right-of-Center Liberal Party (Aussies still use “liberal” in the European sense of classical liberalism).

Unfortunately, I learned that the Australian Liberals (like British Tories) need some remedial work on fiscal policy.

Prime Minister Abbott and his team, for instance, have proposed to increase Australia’s top tax rate. Here’s some of what’s been reported by the Australian Financial Review.

The Abbott government’s deficit tax means top earners will face a 49 per cent marginal tax rate, the eighth highest among developed countries. …. Australia already holds one of the highest personal income and company tax rates in the OECD. The 30 per cent corporate tax rate and 45 per cent personal income tax rate are higher than the average of 25.32 per cent for companies and 41.51 per cent for individuals. A personal tax increase will worsen the impact of “bracket creep”. …a higher income tax rate could also make Australia less competitive globally.

And the AFR also reports that a visiting scholar has thrown cold water on the idea of mimicking European fiscal policy.

Professor Prescott, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 2004, …said that at 49 per cent the top marginal tax rate would hurt growth and the government should redouble its efforts to bring down expenditure instead. “It’s too high,” said Professor Prescott, who has written on the negative impact of increased taxes on economic growth in Europe. “You’re killing the goose that lays the golden egg.” …Lamenting “as sad” the standard of public and academic debate over budget deficits – both here and abroad – Professor Prescott said the focus should be on productivity and government spending. “What matters is expenditure. To spend is to tax and to tax is to depress.”

So why is an ostensibly right-of-center government copying Obama’s class warfare tax policy?

Beats me, though I’m told it’s because the politicians in Canberra (the nation’s capital) thinks this will appease the left and show “fairness.”

I imagine that strategy will be a flop, just like the first President Bush didn’t win any friends when he capitulated to a tax hike in 1990.

In any event, the Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance warns that the tax hike may lose revenue because of Laffer Curve effects.

“The idea of increasing the top marginal tax rate in Australia is unlikely to raise any revenue, and may actually decrease government revenue due to a shrinking in the tax base, as high-income people reduce their labour supply, investment, innovation and tax compliance,” said John Humphreys, the deputy director of the Australian Taxpayers Alliance and an economics lecturer at the University of Queensland. …“Based on mainstream estimates of the high-income elasticity of taxable income, it is fairly straight forward to calculate the tax rate that will raise the maximum amount of revenue, and in Australia that is about 45%. If tax is increased beyond that level, then it is unlikely to raise revenue, and may actually cause a drop in revenue.…” The modeling by Humphreys is due to be published in Policy Journal in the coming months.

I’m skeptical about the finding that the revenue-maximizing rate for the personal income tax is 45 percent, particularly when there is very rigorous analysis suggesting that 20 percent is much closer to the mark.

But I definitely agree that pushing the rate to 49 percent will backfire on the Australian government.

And the folks at the ATA do make the very sound point that politicians shouldn’t try to set the top rate at the revenue-maximizing level regardless.

“There is no logical argument for increasing marginal tax rates about the revenue-maximising level, and indeed there is no good argument for having tax rates anywhere near the revenue-maximising level since those taxes raise very little money but cause significant economic damage.”

Amen. Indeed, allow me to call your attention to some very impressive academic work on this issue.

Now let’s shift to the spending side of Australian fiscal policy.

The good news is that the Abbott government isn’t proposing big increases in the burden of government spending.

The bad news, however, is that there doesn’t seem to be any commitment to a short-term or long-term effort to shrink the public sector.

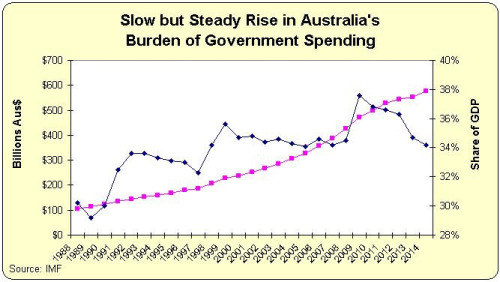

Here’s a chart, based on IMF data, looking at what’s happened to Australian government spending over the past 20-plus years. The purple-ish line is nominal government spending (left axis) and the blue line is government spending as a share of economic output (right axis).

In the long run, the trend of the blue line is the most important variable.

Unfortunately, the burden of government spending has climbed since the late 1980s. It’s still much lower than the burden of spending in places such as France, but the line is moving in the wrong direction.

On the other hand, if you look at the data since 2000, you could accurately say that Australian policy makers have succeeded in keeping the burden of spending from climbing above 34 percent of GDP (there was some foolish stimulus spending beginning back in 2009, but it didn’t lead to a permanent expansion in the size of government).

But let me share some remarkable data showing Australia’s missed fiscal opportunity. If you look at the IMF’s annual government spending and do the calculations, you’ll find that government spending since 1988 has grown by an average of 6.8 percent each year.

Since nominal GDP also has increased at a good pace, the actual burden of government has “only” risen from about 30 percent to 34 percent of economic output.

But imagine if Australian policy makers had merely imposed some version of Mitchell’s Golden Rule and limited spending so that it grew by, say, 3 percent annually.

If they had engaged in that modest level of fiscal restraint, the burden of the public sector today would be only about half its current size. In other words, government spending in Australia would be less than 17 percent of economic output, which would be even better than Hong Kong and Singapore.

This explains why I’m so fixated on expenditure limitations. You can make big progress over just a couple of decades if politicians somehow can be convinced to restrain the rate of growth of government spending.

Or, as the people of Switzerland figured out, you can enjoy that progress if you impose a spending limit on the politicians.