Washington is filled with debate and discussion about the economic burden of the federal income tax, which collected $1.13 trillion in FY2012 ($1.37 trillion if you include the corporate income tax).

Yet politicians rarely consider the economic impact of payroll taxes, even though these levies totaled $.85 trillion during the same fiscal year.

Yet politicians rarely consider the economic impact of payroll taxes, even though these levies totaled $.85 trillion during the same fiscal year.

Yes, we had a gimmicky payroll tax holiday for the past few years. And it’s true that Obama has signaled that he wants to increase the payroll tax burden at some point to prop up the Social Security system.

But there’s rarely, if ever, a discussion of wholesale reform.

That’s actually a good thing. Compared to the income tax, the payroll tax does far less damage. And it’s not just because it collects less money. On a per-dollar-raised basis, the payroll tax is considerably less destructive than the income tax.

Why? Because it’s actually a form of flat tax.

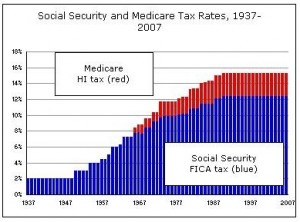

- It has only one tax rate. There’s a 12.4 percent tax for Social Security and a 2.9 percent tax for Medicare, which means a flat tax of 15.3 percent.

- There’s almost no double taxation. The payroll tax applies to wage and salary income, as well as personal earnings from business activities (sometimes known as “Schedule C” income). But dividends, interest, and capital gains are generally spared – other than the 3.8 percent Obamacare surtax.

- There are no loopholes or deductions for politically connected interest groups.

And because of these three features, the tax is remarkably simple and doesn’t even require a tax form unless taxpayers have Schedule C income.

None of this, by the way, means the payroll tax is a good or desirable levy.

- It takes for too much money from the American people and is far and away the biggest tax paid by the majority of American workers.

- Those revenues are used for two programs – Social Security and Medicare – that are actuarially bankrupt and contributing to the nation’s long-run fiscal collapse.

- The 15.3 percent tax undermines work incentives by driving a wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption.

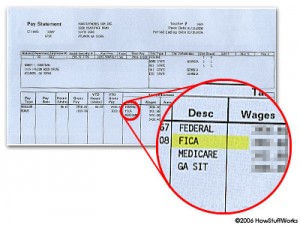

- And the tax is very non-transparent, particularly since many taxpayers don’t even realize that the “F.I.C.A.” tax on their pay stub only reflects 50 percent of their payroll tax burden. In a hidden form of pre-withholding, employers pay an equal amount to the government on behalf of their workers – funds that otherwise would be part of worker compensation.

In other words, the payroll tax is a bad imposition. That being said, it still does considerably less damage, on a per-dollar-collected basis, than the income tax.

With that in mind, I’m puzzled that some folks want to keep the income tax and get rid of the payroll tax.

My friends at the Heritage Foundation, for instance, have a tax reform proposal that would fold the payroll tax into the income tax. Since they’re also proposing to turn the income tax into a form of flat tax, with one rate and no double taxation, the overall proposal clearly is a big improvement over today’s tax system. But all of the improvement is because of reforms to the income tax.

The Washington Examiner has an even stranger position. The paper recently editorialized in favor of abolishing the Social Security portion of the payroll tax and expanding the income tax.

The payroll tax — 12.4 percent, split between workers and their employers to help finance Social Security – is one of the worst taxes on the books for several reasons. A basic economic principle is that when the government taxes something, the nation gets less of it. Because the payroll tax makes it more expensive and administratively burdensome for businesses to hire workers, it’s a drag on employment. Also, even the employer’s share of the tax is effectively passed on to workers in the form of lower salaries and benefits.

There’s nothing overtly wrong with the above passage. The tax does all those bad things. But the income tax does all those things as well, but in an even more destructive fashion.

The editorial addresses a couple of potential objections, starting with the notion that the payroll tax is a revenue dedicated to social Security.

There are two main objections to scrapping the payroll tax. The first is the theoretical idea that payroll taxes are a dedicated revenue stream for Social Security. In practice, it just isn’t true. All government expenditures ultimately come from the same place. Payroll taxes help subsidize other government functions, and the government will use other tax revenue and borrowing to pay for Social Security when revenues are short.

They’re right that all taxes basically get dumped into the same pile of money and that the relationship between payroll taxes and Social Security benefits is imprecise.

But since my argument has nothing to do with this issue, I don’t think it matters.

Here’s the part of the editorial that doesn’t make sense.

The other objection is the massive revenue hit to the federal government. In 2010 (the last year before the recent payroll tax holiday), social insurance taxes raised $865 billion in revenue, according to the Congressional Budget Office. But there are a number of ways to recoup that revenue. As stated above, eliminating the payroll tax would make it easier to get rid of a lot of credits, loopholes and deductions. Also, if lower-income Americans aren’t paying payroll taxes, they can pay a bit more in income taxes. This would also deal with a conservative complaint that the income tax system needs to be reformed so everybody has at least some skin in the game.

This passage has a policy mistake and a political mistake.

The policy mistake is that the proposed swap almost surely would make the overall tax code more hostile to growth. The Examiner is proposing to get rid of an $865 billion tax that does a modest amount of damage per dollar collected, and somehow make up for that foregone revenue by collecting an additional $865 billion from the income tax system – which we know does a very large amount of damage per dollar collected.

To be sure, it’s possible to collect that extra money by eliminating distortions such as the state and local tax deduction or the healthcare exclusion. Compared to raising marginal tax rates, those are much-preferred ways of generating more revenue. But even in a best-case scenario – with politicians miraculously trying to collect an extra $865 billion without making the income tax system even worse, it’s hard to envision a better fiscal regime if we swap the payroll tax for a bigger income tax.

The political mistake is the assumption that more people will have “skin in the game” if the income tax is expanded. That’s almost surely not true. The poor don’t pay income tax, but the payroll tax grabs 15.3 percent of every penny earned by low-income households. And since very few taxpayers pay attention to which tax is shrinking their paychecks, it doesn’t really matter whether the “skin” is a payroll tax or an income tax.

The political mistake is the assumption that more people will have “skin in the game” if the income tax is expanded. That’s almost surely not true. The poor don’t pay income tax, but the payroll tax grabs 15.3 percent of every penny earned by low-income households. And since very few taxpayers pay attention to which tax is shrinking their paychecks, it doesn’t really matter whether the “skin” is a payroll tax or an income tax.

Since the Examiner isn’t proposing a specific plan, there’s no way of making a definitive statement, but it’s 99 percent likely that eliminating the Social Security payroll tax would result in low-income households paying even less money to Washington. I think everybody should send less to Washington, but I don’t think shifting a greater share of the tax burden onto the middle class and the rich is the right way of achieving that goal.

I have one final objection, and this applies to both the Heritage Foundation plan and the Examiner proposal.

Notwithstanding everything I just wrote, I actually agree with them that we should eliminate the Social Security payroll tax. But we should get rid of the tax as part of a transition to a system of personal retirement accounts.

This is a reform that has been successfully implemented in about 30 nations and it also should happen in the United States. But an integral feature of this reform is that workers would be allowed to shift their payroll taxes into personal accounts. Needless to say, that’s not possible if the payroll tax has disappeared.

This video explains why genuine Social Security reform is so desirable.

And let’s not forget that the Medicare portion of the payroll tax could and should be part of a broader agenda of entitlement reform. But that’s also less likely if the payroll tax is folded into the income tax.