One of my missions in life is fundamental tax reform. I would like to replace the corrupt internal revenue code with a simple and fair flat tax.

Though what I really want is a tax system that minimizes the damage of extracting money from the productive sector of the economy, so I’ll take any system with a low rate, no double taxation, and no distortionary loopholes.

The national sales tax, for instance, also would be a good option if we can first repeal the 16th Amendment so there’s no risk that politicians would pull a bait and switch and saddle us with both an income tax and a sales tax (and in my ultimate fantasy world, we would shrink the federal government to the size envisioned by the Founding Fathers, in which case we probably wouldn’t need any broad-based tax at all).

While I normally make the economic case for tax reform, there are many reasons to fix our broken tax code.

Many Americans, for instance, are rightfully upset that the tax code is a 76.000-page monstrosity that enables the politically well connected to benefit from special provisions.

So we don’t know if the rich are paying an appropriate amount. Some of them are paying too much because of high rates and double taxation, while some of them are paying too little because they have clever lawyers, lobbyists, and accountants.

In an ideal world, if someone like Bill Gates earns 10,000 times as much as I do, then he should pay 10,000 times as much in tax. That’s a core principle of the flat tax.

But this post isn’t about why we need tax reform to promote economic growth or fairness. Instead, I want to focus on tax reform as a way of reducing welfare fraud. The Treasury Department just released a report acknowledging that the IRS made more than $100 billion of improper “earned income credit” payments over the past decade and that about one-fourth of all such payments are in error.

This Fox News article is a good summary. Here are the key details.

The Internal Revenue Service paid out more than $110 billion in tax credits over the past decade to people who didn’t qualify for them, according to a Treasury report released Tuesday. …IRS inspector general J. Russell George said more than one-fifth of all credits paid under the program went to people who didn’t qualify. …George said in a statement. “Unfortunately, it is still distributing more than $11 billion in improper EITC payments each year and that is disturbing.” …The agency said it prevents “nearly $4 billion in improper claims each year and is committed to continuing to work to reduce improper claims.” The EITC is one of the nation’s largest anti-poverty programs. In 2011, more than 27 million families received nearly $62 billion in credits.

Now some background. The “earned income credit” or “earned income tax credit” is actually an income redistribution scheme operated by the IRS. It’s basically a wage subsidy. If someone earns money (the “earned income” part), the law says the IRS should augment that money with a payment from the government (the “credit” or “tax credit” part).

The key thing to understand, though, is that the EITC is “refundable,” which is the government’s term for payments to people who don’t earn enough to owe any income tax. That’s why it’s primarily an income redistribution program. Only it’s operated by the IRS rather than the Department of Health and Human Service or some other welfare agency.

And when government is giving away other people’s money, there are those who will try to abuse the program. That’s true for corporate welfare, and it’s true for traditional welfare like food stamps. And, as we see from the Treasury report, it’s true for the EITC.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that the EITC has a redeeming feature. Some lawmakers realized traditional welfare programs were very destructive because they paid people not to work. The EITC supposedly offsets that perverse incentive because you get the money only because you earn some income.

But now let’s share some additional bad news. The government takes away the EITC once your income reaches a certain level, and this is equivalent to a big increase in the marginal tax rate on earning additional income.

But now let’s share some additional bad news. The government takes away the EITC once your income reaches a certain level, and this is equivalent to a big increase in the marginal tax rate on earning additional income.

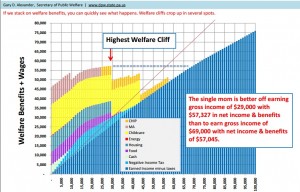

And when you combine the EITC with all the other redistribution programs operated by government, you create a huge dependency trap. Indeed, the chart shows that many of these programs can be larger than the EITC (which is called “negative income tax”).

So let’s adopt a flat tax and get rid of all the bad features of the tax system, including the EITC. Welfare and income redistribution are not proper roles of the federal government.

We’re far more likely to get good results – both for poor people and taxpayers – if we let state and local governments experiment and learn from each other on what actually helps people climb out of poverty.