Regular readers know that one of my main goals is to preserve and promote tax competition as a means of restraining the greed of the political class. Heck, I almost wound up in a Mexican jail because of my work defending low-tax jurisdictions.

As you can imagine, it’s difficult to persuade politicians. After all, why would they support policies such as fiscal sovereignty and financial privacy that hinder their ability to extract more revenue?

So I try to educate them about the link between taxes and growth in hopes that they will understand that a vibrant economy also means a large tax base.

And I specifically tell them that so-called tax havens play a very valuable role since they are an alternative source of investment capital for nations that have undermined domestic investment with bad tax policy.

And I also explain to them that low-tax jurisdictions give companies some much-needed flexibility to maintain operations in an otherwise hostile fiscal environment. Let’s look at that specific issue by reviewing some of the findings from a study by two Canadian economists about tax havens and business activity.

In the introduction to their study, they describe the general concern (among politicians) that competition between governments will lead to lower tax rates.

Increased mobility of goods and services is apt to give rise to an erosion of corporate tax bases in high-tax industrialized countries, a decline in tax revenues and a rise in competition among governments. Countries seeking to attract and retain mobile investment and the associated tax revenues may be induced to reduce tax rates below the levels that would obtain in the absence of mobility. In the view of some commentators, indeed, increased mobility can lead to a “race to the bottom” driving business tax rates to minimal levels, due to the fiscal externalities that mobility creates.

It certainly is true that tax competition has pressured politicians to lower tax rates, and the academic research shows that this is a good thing, notwithstanding complaints by leftists economists such as Jeffrey Sachs.

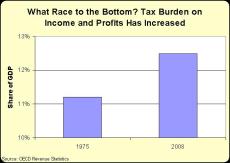

What folks on the left don’t understand is that there is a big difference between tax rates and tax revenue. Thanks in large part to Laffer-Curve effects, the big decline in tax rates in the past three decades has not led to a decline in tax revenues.

What folks on the left don’t understand is that there is a big difference between tax rates and tax revenue. Thanks in large part to Laffer-Curve effects, the big decline in tax rates in the past three decades has not led to a decline in tax revenues.

Indeed, taxes on income and profit, measured as a share of GDP, have increased as tax rates have declined.

But I’m getting distracted. The purpose of this post is to analyze the findings of the two Canadian economists.

Here are their major conclusions, which show that tax havens actually help high-tax nations by allowing companies to engage in “real economic activities” in spite of punitive tax policies.

Financial mobility is manifested in the decisions of multinational enterprises to separate research and development and capital financing activities from production and sales of outputs, and so to engage in “tax planning” to realize income from intellectual property and from capital in jurisdictions different from those where real economic activities are located. …While tax planning may reduce revenues of high-tax jurisdictions, therefore, it may have offsetting effects on real investment that are attractive to governments. In principle, then, the presence of international tax planning opportunities may allow countries to maintain or even increase high business tax rates, while preventing an outflow of foreign direct investment. …the investment-enhancing effects of international tax planning can dominate the revenue-erosion effects. The implications of this view are strong: an increase in international tax avoidance can lead to…an increase in the welfare of citizens of high-tax countries. …consistent with our model, governments may be reluctant to close such “loopholes,” because of fears of losses in multinational employment and, in particular, expatriations of ownership and headquarters operations to low-tax countries. …revenue losses due to tax planning are irrelevant, and what matters is the effect of tax planning on the level of multinational investment in high-tax countries and its deadweight costs for the economy, if any.

In other words, tax havens make it possible for companies to indirectly reduce their overall tax burden, thus making it economically feasible to continue operating – and retaining jobs – in nations with bad tax policy.

Other economists have reached similar conclusions. At about the 7:20 mark of this video, I cite research by Mihir Desai, Fritz Foley, and James Hines that also found that tax havens facilitate greater economic activity in high-tax nations.