If I live to be 100 years old, I suspect I’ll still be futilely trying to educate politicians that there’s not a simplistic linear relationship between tax rates and tax revenue.

You can’t double tax rates, for instance, and expect to double tax revenue. Simply stated, there’s another variable – called taxable income – that needs to be added to the equation.

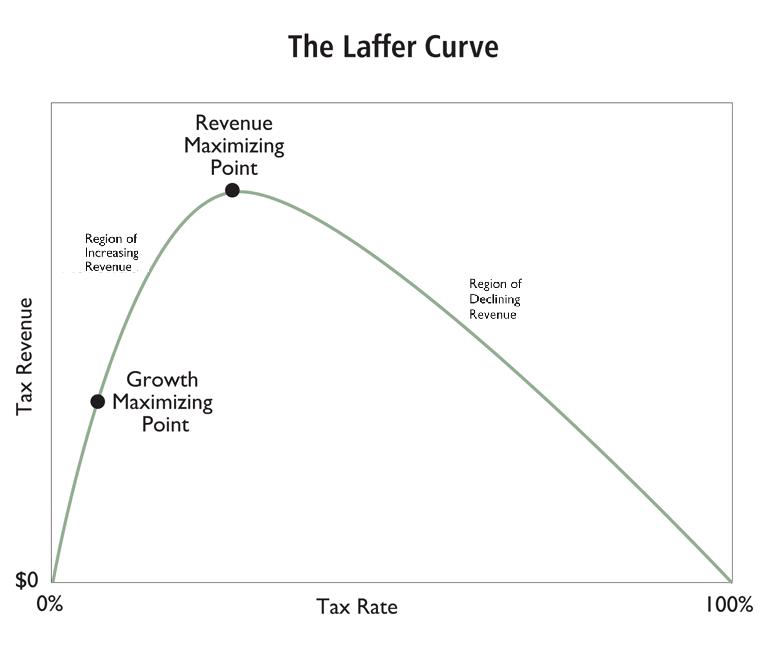

This simple insight is what gives us the Laffer Curve.

This is common sense in the business community. No restaurant owner would ever be foolish enough to think that revenues will double if all prices increase by 100 percent. People in the real world know that this would mean lower sales.

At best, revenues will rise by much less than 100 percent in that scenario. And if sales drop by enough, revenues may actually fall.

Perhaps because so few of them have business experience, it seems that politicians have a hard time grasping this simple concept.

The latest examples come from Europe, where the never-ending greed for more revenue has resulted in the imposition of financial transaction taxes.

So how’s that working out? Are politicians collecting the revenue they expected?

Hardly. Here are some of the details from a City A.M. column.

…taxes on financial transactions across Europe have devastated market activity and failed to raise as much as politicians hoped, according to new figures out yesterday.

The article cites three powerful examples, starting with Hungary.

Hungary implemented a 0.1 per cent tax at the start of the year. But it raised less than half the revenue the state had hoped for, bringing in 13bn Hungarian Forints (£36m) in January.

Wow, less than 50 percent of the revenue that politicians were expecting. But the politicians probably don’t care about the collateral damage they’re imposing on the economy because they’ll get to buy votes with another 13 billion Forints (about $55 million).

Now let’s see how the French are doing.

Now let’s see how the French are doing.

France forged ahead on its own, introducing a 0.2 per cent tax on sales of shares of major firms. But that only raised €200m (£169.4m) from August to November, well below to €530m expected.

Gee, what a shame, the politicians in Paris are only getting about one-third as much money as they were expecting. That’s even worse than Hungary.

But they’ll surely squander that bit of cash as fast as possible.

Our last example comes from Italy. There are no revenue numbers yet, but the decline in financial activity suggests this tax also will be a flop.

And Italy launched its FTT this month. Figures from TMF Group suggest it has cut trading volumes by 38 per cent already

Though politicians may decide it’s a success since they may get more than 50 percent of what they were originally estimating.

That kind of forecasting error would get somebody fired at any private business, but being a politician means never having to say you’re sorry.

And it certainly never means learning from mistakes. The evidence on the Laffer Curve is ubiquitous, with powerful examples in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Italy, France, Spain, as well as Bulgaria and Romania. Or states such as Illinois, Oregon, Florida, Maryland, Washington, DC, and New York.

P.S. Even President Obama has sort of acknowledged the supply-side principles that are the basis of the Laffer Curve.

P.P.S. Remember that the goal of good tax policy is NOT to maximize revenue.

P.P.P.S. I warned the European Union’s Taxation Commissioner about the dangers of a tax on financial transactions last year. Needless to say, my sage counsel appears to have been ignored.