Daniel Hannan is a member of the European Parliament from England. He is one of the few economically sensible people in that body, as demonstrated in these short clips of him speaking about tax competition and deriding the European Commission’s corrupt racket.

And as you can see from his latest article in the UK-based Telegraph, he’s also very wise on issues of class warfare tax policy and Laffer Curve responses to punitive taxation.

France’s richest man, Bernard Arnault, is shifting his fortune to Belgium. Gérard Depardieu, the country’s greatest actor (figuratively and literally)is moving to Russia. And, if rumours are to be believed, Nicolas Sarkozy is planning a new career in London. That’s the problem with very high taxes – they don’t redistribute wealth; they redistribute people. …the rich don’t sit around waiting to be taxed. …many financiers can open their businesses abroad simply by opening their laptops. The result of a hike in tax rates is thus often a fall in tax revenue – which means, of course, that the rest of us end up paying more to cover the share of the departed plutocrats.

Hannan understands that rich people have considerable control over the timing, level, and composition of their income, which is precisely why there are powerful Laffer Curve effects when politicians go after the so-called rich (as I tried to explain in a lesson for President Obama).

But Hannan also makes a good point about complexity.

The complexity of a tax system is every bit as damaging to competitiveness as the overall tax rate. The more convoluted the tax code becomes, the more time we have to take off work to comply with it.Tolley’s Tax Handbook is now 11,500 pages long, twice what it was when Gordon Brown became chancellor, and the number of tax lawyers has increased commensurately. …The very wealthy, who can afford ingenious tax advisers and high upfront fees, turn this complexity to their advantage, sheltering their assets in various pockets unintentionally created by government schemes. Again, the rest of us then have to pay more to make up their portion.

Since we have 72,000 pages of complexity and corruption in our tax code, I can’t help but comment that the Brits are lucky that they “only” have 11,500 pages (assuming, of course, that the methodology in both page counts is similar).

In both cases, though, Hannan is right in stating that complexity benefits those who can hire lots of tax lawyers, financial planners, accountants, and other tax advisers.

The answer, of course, is a flat tax. Hannan doesn’t explicitly embrace that option, but he does write about the benefits of lower rates and fewer distortions.

There is one other point he makes that is worth noting. He cites a former Labour Party politician who explicitly was willing to have less prosperity if it meant more equality.

You might, of course, agree with Roy Hattersley, who once said that he’d rather have 5% more equality than 10% more prosperity. That is a respectable position, but at least be honest about it. Wealth taxes create more equal, but poorer societies.

Margaret Thatcher eviscerated that destructive mentality many years ago in this famous speech, but this is an area where  proponents of limited government need to do more work.

proponents of limited government need to do more work.

There are plenty of well-meaning people who mistakenly think the economy is a fixed pie. If we want to help them understand the benefits of small government and free markets, we need to come up with more effective ways of educating them about the important implications of even small differences in economic growth.

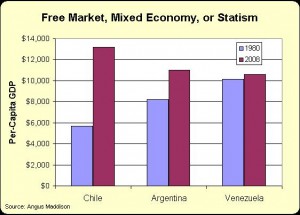

I try to make that point in this PBS interview, but I suspect these charts comparing North Korea and South Korea and comparing Chile, Argentina, and Venezuela are much more compelling.