It’s probably not an exaggeration to say that the United States has the world’s worst corporate tax system.

We definitely have the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world, and we may have the highest corporate tax rate in the entire world depending on how one chooses to classify the tax regime in an obscure oil Sheikdom.

But America’s bad policy goes far beyond the rate structure. We also have a very punitive policy of “worldwide taxation” that forces American firms to pay an extra layer of tax when competing for market share in other nations.

And then we have rampant double taxation of both dividends and capital gains, which discourages business investment.

No wonder a couple of German economists ranked America 94 out of 100 nations when measuring the overall treatment of business income.

So if you’re an American company, how do you deal with all this bad policy?

Well, one solution is to engage in a lot of clever tax planning to minimize your taxable income. Though that’s probably not a successful long-term strategy since the Obama Administration is supporting a plan by European politicians to create further disadvantages for American-based companies.

Another option is to somehow turn yourself into a foreign corporation. You won’t be surprised to learn that politicians have imposed punitive anti-expatriation laws to make that difficult, but the crowd in Washington hasn’t figured out how to stop cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

And it seems that’s a very effective way of escaping America’s worldwide tax regime. Let’s look at some excerpts from a story posted by CNBC.

Some of the biggest mergers and acquisitions so far in 2013 have involved so-called “tax inversions” – where a US acquirer shifts overseas, to Europe in particular, to pay a lower rate.

The article then lists a bunch of examples. Here’s Example #1.

Michigan-based pharmaceuticals group Perrigo has said its acquisition of Irish biotech company Elan will lead to re-domiciling in Ireland, where it has given guidance it expects to pay about 17 per cent in tax, rather than an estimated 30 per cent rate it was paying in the US. Deutsche Bank estimates Perrigo will achieve tax savings of $118m a year as a result.

And Example #2.

New Jersey-based Actavis’s acquisition of Warner Chilcott in May – will also result in a move to Ireland, where Actavis’s tax rate will fall to about 17 per cent from an effective rate of 28 per cent tax, and enable it to save an estimated $150m over the next two years.

Then Example #3.

US advertising company Omnicom has said its $35bn merger with Publicis will result in the combined group’s headquarters being located in the Netherlands, saving about $80m in US tax a year.

Last but not least, Example #4.

Liberty Global’s $23bn acquisition of Virgin Media will allow the US cable group to relocate to the UK, and pay its lower 21 per cent tax rate of corporation tax.

And we can expect more of these inversions in the future.

M&A advisers say the number of companies seeking to re-domicile outside the US after a takeover is rising. …Increased use of tax inversion has coincided with an intensifying political debate on US tax – with Democrats, Republicans and the White House agreeing that the current code, which imposes a top rate of 35 per cent but offers a plethora of tax breaks, is in need of reform.

I’ll close with a very important point.

It’s not true that the current code has a “plethora of tax breaks.” Or, to be more specific, there are lots of tax breaks, but the ones that involve lots of money are part of the personal income tax, such as the state and local tax deduction, the mortgage interest deduction, the charitable contributions deduction, the muni-bond exemption, and the fringe benefits exclusion.

There are some corrupt loopholes in the corporate income tax, to be sure, such as the ethanol credit for Big Ag and housing credits for politically well-connected developers. But if you look at the Joint Committee on Taxation’s list of so-called tax expenditures and correct for their flawed definition of income, it turns out that there’s not much room to finance a lower tax rate by getting rid of unjustified tax breaks.

So does this mean there’s no way of fixing the problems that cause tax inversions?

If lawmakers put themselves in the straitjacket of “static scoring” as practiced by the Joint Committee on Taxation, then a solution is very unlikely.

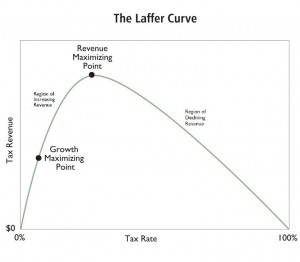

But if they choose to look at the evidence, they’ll see that there are big Laffer-Curve effects from better tax policy. A study from the American Enterprise Institute found that the revenue-maximizing corporate tax rate is about 25 percent while more recent research from the Tax Foundation puts the revenue-maximizing tax rate for companies closer to 15 percent.

I should hasten to add that the tax code shouldn’t be designed to maximize revenues. But when tax rates are punitively high, even a cranky libertarian like me won’t get too agitated if politicians wind up with more money as a result of lowering tax rates.

You might think that’s a win-win situation. Folks on the right support lower tax rates to get more growth and folks on the left support the same policy to raise more tax revenue.

But there’s at least one person on Washington who wants high tax rates even if they don’t raise additional revenue.