I damned Obama with faint praise last year by asserting that he would never be able to make America as statist as France.

My main point was to explain that the French people, notwithstanding their many positive attributes, seem hopelessly statist. At least that’s how they vote, even though they supposedly support spending cuts according to public opinion polls.

More specifically, they have a bad habit of electing politicians – such as Sarkozy and Hollande – who think the answer to every question is bigger government.

As such, it’s almost surely just a matter of time before France suffers Greek-style fiscal chaos.

But perhaps I should have taken some time in that post to explain that the Obama Administration – despite its many flaws – is genuinely more market-oriented that its French counterpart.

Or perhaps less statist would be a more accurate description.

However you want to describe it, there is a genuine difference and it’s manifesting itself as France and the United States are fighting over the degree to which governments should impose international tax rules designed to seize more tax revenue from multinational companies.

Here’s some of what the UK-based Guardian is reporting.

France has failed to secure backing for tough new international tax rules specifically targeting digital companies, such as Google and Amazon, after opposition from the US forced the watering down of proposals that will be presented at this week’s G20 summit. Senior officials in Washington have made it known they will not stand for rule changes that narrowly target the activities of some of the nation’s fastest growing multinationals, according to sources with knowledge of the situation.

This is very welcome news. The United States has the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world and the overall tax system for companies ranks a lowly 94 out of 100 nations in a survey of “tax attractiveness” by German economists.

So it’s good that U.S. government representatives are resisting schemes that would further undermine the competitiveness of American multinationals.

Particularly since the French proposal also would enable governments to collect lots of sensitive personal information in order to enforce the more onerous tax regime.

…the US and French governments have been at loggerheads over how far the proposals should go. …Despite opposition from the US, the French position – which also includes a proposal to link tax to the collection of personal data – continues to be championed by the French finance minister, Pierre Moscovici.

It’s worth noting, by the way, that the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has been playing a role in this effort to increase business tax burdens.

The OECD plan has been billed as the biggest opportunity to overhaul international tax rules, closing loopholes increasingly exploited by multinational corporations in the decades since a framework for bilateral tax treaties was first established after the first world war. The OECD is expected to detail up to 15 areas on which it believes action can be taken, setting up a timetable for reform on each of between 12 months and two and a half years.

Just in case you don’t have your bureaucrat-English dictionary handy, when the OECD says “reform,” it’s safe to assume that it means “higher taxes.”

Maybe it’s because the OECD is based in France, where taxation is the national sport.

France has been among the most aggressive in responding to online businesses that target French customers but pay little or no French tax. Tax authorities have raided the Paris offices of several firms including Google, Microsoft and LinkedIn, challenging the companies’ tax structures.

But British politicians are equally hostile to the private sector. One of the senior politicians in the United Kingdom actually called a company “evil” for legally minimizing its tax burden!

In the UK, outcry at internet companies routing British sales through other countries reached a peak in May after a string of investigations by journalists and politicians laid bare the kinds of tax structures used by the likes of Google and Amazon. …Margaret Hodge, the chair of the public accounts committee, called Google’s northern Europe boss, Matt Brittin, before parliament after amassing evidence on the group’s tax arrangements from several whistleblowers. After hearing his answers, she told him: “You are a company that says you do no evil. And I think that you do do evil” – a reference to Google’s corporate motto, “Don’t be evil”.

Needless to say, Google should be applauded for protecting shareholders, consumers, and workers, all of whom would be disadvantaged if government seized a larger share of the company’s earnings.

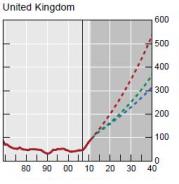

And if Ms. Hodge really wants to criticize something evil, she should direct her ire against herself and her colleagues. They’re the ones who have put the United Kingdom on a path of bigger government and less hope.

And if Ms. Hodge really wants to criticize something evil, she should direct her ire against herself and her colleagues. They’re the ones who have put the United Kingdom on a path of bigger government and less hope.

Let’s return to the main topic, which is the squabble between France and the United States.

Does this fight show that President Obama can be reasonable in some areas?

The answer is yes…and no.

Yes, because he is resisting French demands for tax rules that would create an even more onerous system for U.S. multinationals. And it’s worth noting that the Obama Administration also opposed European demands for higher taxes on the financial sector back in 2010.

But no, because there’s little if any evidence that he’s motivated by a genuine belief in markets or small government.* Moreover, he only does the right thing when there are proposals that unambiguously would impose disproportionate damage on American firms compared to foreign companies. And it’s probably not a coincidence that the high-tech sector and financial sector have dumped lots of money into Obama’s campaigns.

Let’s close, however, on an optimistic note. Whatever his motive, President Obama is doing the right thing.

This is not a trivial matter. When the OECD started pushing for changes to the tax treatment of multinationals earlier this year, I was very worried that the President would join forces with France and other uncompetitive nations and support a “global apportionment system for determining corporate tax burdens.

Based on the Guardian’s report, as well as some draft language I’ve seen from the soon-to-be-released report, it appears that we have dodged that bullet.

At the very least, this suggests that the White House was unwilling to embrace the more extreme components of the OECD’s radical agenda. And since you can’t impose a global tax cartel without U.S. participation (just as OPEC wouldn’t succeed without Saudi Arabia), the statists are stymied.

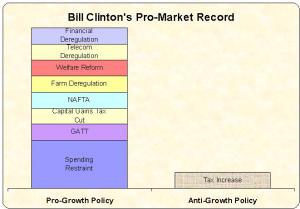

So two cheers for Obama. I’m not under any illusions that the President is turning into a genuine centrist like Bill Clinton, but I’ll take this small victory.

* Obama did say a few years ago that “no business wants to invest in a place where the government skims 20 percent off the top,” so maybe he does understand the danger of high tax rates. And the President also said last year that we should “let the market work on its own,” which may signal an awareness that there are limits to interventionism. But don’t get your hopes up. There’s some significant fine print and unusual context with regard to both of those statements.