What’s the worst thing about Delaware?

No, not Joe Biden. He’s just a harmless clown and the butt of some good jokes.

Instead, the so-called First State is actually the Worst State because 100 years ago, on this very day, Delaware made the personal income tax possible by ratifying the 16th Amendment.

Though, to be fair, I suppose the 35 states that already had ratified the Amendment were more despicable since they were even more anxious to enable this noxious levy (and Alabama was first in line, which is a further sign that Georgia deserved to win the Southeastern Conference Championship Game, but I digress).

Let’s not get bogged down in details. The purpose of this post is not to re-hash history, but to instead ask what lessons we can learn from the adoption of the income tax.

The most obvious lesson is that politicians can’t be trusted with additional powers. The first income tax had a top tax rate of just 7 percent and the entire tax code was 400 pages long. Now we have a top tax rate of 39.6 percent (even higher if you include additional levies for Medicare and Obamacare) and the tax code has become a 72,000-page monstrosity.

But the main lesson I want to discuss today is that giving politicians a new source of money inevitably leads to much higher spending.

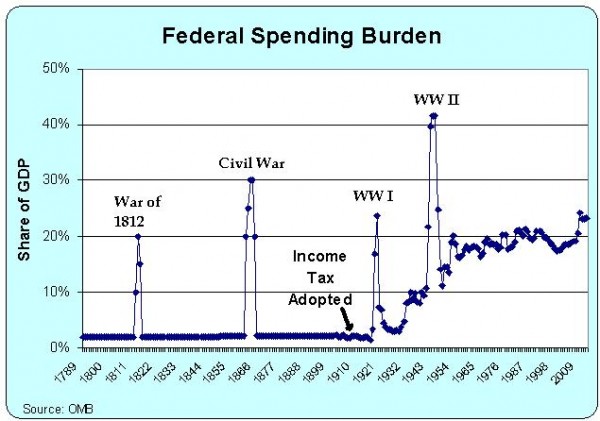

Here’s a chart, based on data from the Office of Management and Budget, showing the burden of federal spending since 1789.

Since OMB only provides aggregate spending data for the 1789-1849 and 1850-190 periods, which would mean completely flat lines on my chart, I took some wild guesses about how much was spent during the War of 1812 and the Civil War in order to make the chart look a bit more realistic.

But that’s not very important. What I want people to notice is that we enjoyed a very tiny federal government for much of our nation’s history. Federal spending would jump during wars, but then it would quickly shrink back to a very modest level – averaging at most 3 percent of economic output.

So what’s the lesson to learn from this data? Well, you’ll notice that the normal pattern of government shrinking back to its proper size after a war came to an end once the income tax was adopted.

In the pre-income tax days, the federal government had to rely on tariffs and excise taxes, and those revenues were incapable of generating much revenue for the government, both because of political resistance (tariffs were quite unpopular in agricultural states) and Laffer Curve reasons (high tariffs and excise taxes led to smuggling and noncompliance).

But once the politicians had a new source of revenue, they couldn’t resist the temptation to grab more money. And then we got a ratchet effect, with government growing during wartime, but then never shrinking back to its pre-war level once hostilities ended (Robert Higgs wrote a book about this unfortunate phenomenon).

The same thing happened in Europe. The burden of government spending used to be quite modest on the other side of the Atlantic, with outlays consuming only about 10 percent of economic output.

Once European politicians got the income tax, however, that also enabled a big increase is the size of the state.

But Europe also gives us a very good warning about the dangers of giving politicians a second major source of revenue.

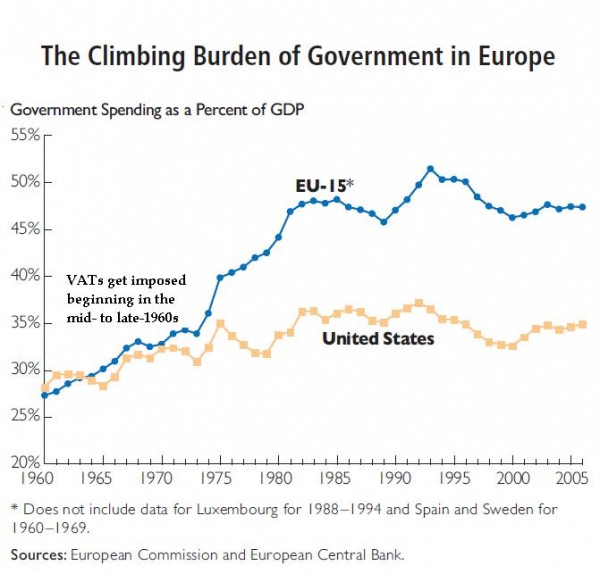

Here’s a chart I prepared for a study published when I was at the Heritage Foundation. You’ll notice from 1960-1970 that the overall burden of government spending in Europe was not that different than it was in the United States.

That’s about the time, however, that the European governments began to impose value-added taxes.

The rest, as they say, is history.

I’m not claiming, by the way, that the VAT is the only reason why the burden of government spending expanded in Europe. The Europeans also impose harsher payroll taxes and higher energy taxes. And their income taxes tend to be much more onerous for middle-income households.

But I am arguing that the VAT helped enable bigger government in Europe, just like the income tax decades earlier also enabled bigger government in both Europe and the United States.

So ask yourself a simple question: If we allow politicians in Washington to impose a VAT on top of the income tax, do you think they’ll use the money to expand the size and scope of government?

If it takes more than three seconds to answer that question, I suggest you emigrate to France as quickly as possible.

P.S. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that the crazy bureaucrats at the Paris-based OECD think the VAT is good for growth and jobs. Sort of makes you wonder why we’re subsidizing those statists with American tax dollars.