Statists are in a tough position. For years, they’ve been saying the United States should be more like Europe.

And, as shown in these very funny cartoons by Michael Ramirez and Bob Gorrell, President Obama is a cheerleader for that effort.

But now Europe’s welfare states are collapsing, so the left is scrambling to come up with some way of rationalizing their support for ever-growing levels of taxation and spending

Paul Krugman’s been doing what he can to square this circle, complaining that Europe is in trouble because governments aren’t spending enough. Sounds preposterous, but at least he provides some comfort for the don’t-confuse-us-with-the-facts-we’re-Keynesians crowd.

But for those who prefer to look at real data, one of my Cato Institute colleagues has sorted through the numbers to see whether Krugman’s hypothesis has any validity. Here’s some of what Alan Reynolds wrote for Investor’s Business Daily, reprinted by Real Clear Politics, starting with a quick look at some nations that experienced growth during periods when the burden of government spending was falling.

In Iceland, which didn’t throw taxpayer money at the banks, government spending was slashed from 57.6% of GDP in 2008 to 46.5% in 2012. The deficit fell from 12.9% of GDP to 3.4%. The economy began to recover in 2011. Iceland’s economic boost from fiscal frugality was neither unorthodox nor unique. After all, the U.S. economy boomed in the late 1990s when federal spending was cut from 22.3% of GDP in 1991 to 18.2% in 2000. In Canada, total federal and provincial spending was deeply slashed from 53.2% of GDP in 1992 to 39.2% in 2007 with only salubrious effects.

But what about Krugman’s argument that spending cuts have hurt growth in nations such as Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, Great Britain, and Spain?

Well, Alan points out that these nations haven’t reduced spending.

The PIIGGS imposed no austerity at all on the public sector in the past five years. Government spending on bailouts, subsidies, grants, salaries and entitlements commands a much larger share of these economies than it did just a few years ago.

If you break down the data on an annual basis, some of these nations have been forced by the financial crisis to finally reduce their budgets, but the cuts in the past year or two aren’t nearly enough to make up for the huge spending increases in earlier years.

But these governments have shown no reluctance to raises taxes. I’ve already discussed their unfortunate propensity to hike value-added tax rates. Alan explains that they’re doing the same thing for income tax rates.

European austerity has been focused on the private sector — namely, taxpayers with high incomes. That is the second thing the PIIGGS have in common. The highest income tax rate was recently increased in every one of the troubled PIIGGS except Italy (where it was already too high at 43%). The top tax rate was hiked from 40 to 46.5% in Portugal, from 41 to 48% in Ireland, from 40 to 45% in Greece, from 40 to 50% in Great Britain, and from 48 to 52% in Spain.

In other words, Veronique de Rugy is correct. The “austerity” in Europe generally has been in the form of higher taxes, squeezing the productive sector to prop up the public sector.

Though I would point out that there are a few bright spots. Switzerland has been doing quite well, thanks to a “debt brake” that limits how much the budget can grow each year.

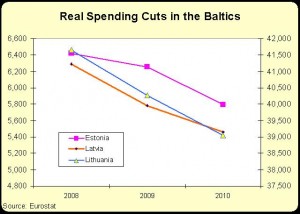

And the Baltic nations deserve credit for imposing genuine budget cuts several years ago, a policy that has yielded big dividends since they’re now growing while most other European nations are mired in economic stagnation.

And the Baltic nations deserve credit for imposing genuine budget cuts several years ago, a policy that has yielded big dividends since they’re now growing while most other European nations are mired in economic stagnation.

And they kept their flat tax systems, showing some appreciation for the common-sense insight that you don’t get more growth by punishing investors, entrepreneurs, and small business owners.

By the way, Alan’s column isn’t completely depressing. He writes that the burden of government spending is reasonable (at least compared to Europe’s bankrupt welfare states) in some of the major emerging economies.

And they’ve focused more on lowering tax rates rather than making them more punitive.

It is enlightening to compare the depressing performance of these tax-and-spend countries to the rapidly-expanding BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) and MIST economies (Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea and Turkey). Government spending is frugal in these countries, averaging 32.1% of GDP in the BRICs and 27.4% for the MIST group. Rather than raising top tax rates, all but one of the BRIC and MIST countries slashed their highest individual income tax rates in half; sometimes lower. Brazil cut the top tax rate from 55 to 27.5%. Russia replaced income tax rates up to 60% with a 13% flat tax. India cut the top tax rate to 30% from 60%. Similarly, the top tax rate was cut from 55 to 30% in Mexico, from 50 to 30% in Indonesia, from 89 to 38% in South Korea, and from 75 to 35% in Turkey. In China, statutory income tax rates can still reach 45% on paper, but that is only for high salaries and is widely evaded. Investment income is subject to a flat tax of 20%, the corporate tax is 15-25%, and China’s extremely low payroll tax adds almost nothing to labor costs.

This doesn’t mean the BRIC and MIST nations deserve high praise. Many of them still get poor scores from Economic Freedom of the World, largely because the regulatory burden is excessive and also because more needs to be done to uphold the rule of law and protect property rights.

But at least most of them aren’t compounding those mistakes with Keynesian spending schemes and class-warfare tax policy.

For more information about nations that have benefited from spending restraint, here’s my video looking at Ireland in the 1980s, New Zealand and Canada in the 1990s, and Slovakia last decade.

The moral of the story, needless to say, is that good things happen when governments comply with Mitchell’s Golden Rule.

P.S. Paul Krugman received some much-deserved abuse when he made false attacks on Estonia’s admirable fiscal policy.